The vertices of a cross-polytope can be chosen as the unit vectors pointing along each co-ordinate axis – i.e. all the permutations of $(±1, 0, 0,\dots, 0)$. The cross-polytope is the convex hull of its vertices.

Consider the section of a cross-polytope $β_n$ with vertices $(±1, 0, 0,\dots, 0)\in\mathbb{R}^n$ by the hyperplane $(1,1,\dots,1)\cdot\mathbf x=d$.

Its total edge length is constant for all $|d|<1$.

I verified it for $n=2,3,4$. I wonder if this is still true for higher dimensions.

For $n=2$, cross-polytope $β_2$ is a square of side length $\sqrt2$. The line $(1,1)\cdot\mathbf{x}=d$ cuts $β_2$ along a segment of constant length $\sqrt2$ for all $|d|<1$.

For $n=3$, cross-polytope $β_3$ is a regular octahedron of edge length $\sqrt2$. The plane $(1,1,1)\cdot\mathbf{x}=d$ cuts $β_3$ along a hexagon the length of whose perimeter is constant $3\sqrt2$ for all $|d|<1$.

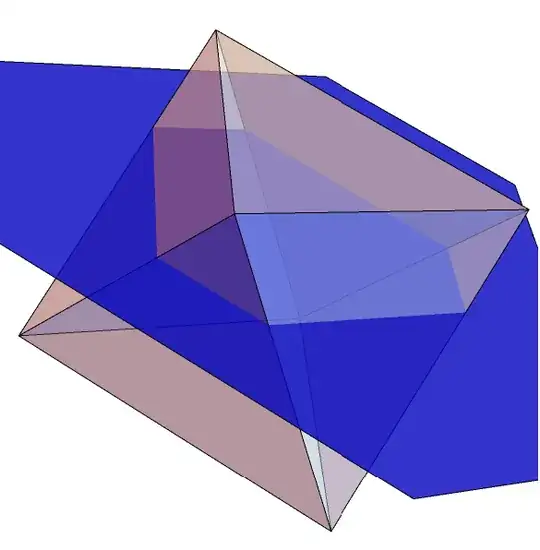

For $n=4$, cross-polytope $β_4$ is a 16-cell of edge length $\sqrt2$. The hyperplane $(1,1,1,1)\cdot\mathbf x=d$ cuts $β_4$ along a solid with 8 triangle faces and 6 rectangle faces. Its total edge length is constant $12\sqrt2$ for all $|d|<1$.