I’m not clear why orthographic projection is different from shadows. If I look at a sphere, I see potentially up to half its surface, yet if the sphere’s shadow is cast onto a plane at the same viewing point, apparently that shadow is only ¼ the area of the sphere? Aren’t both just parallel lines projecting off the sphere? I understand that shadows are the absence of parallel lines of light, and vision is their presence, but it seems weird that the latter would result in double the area.

8 Answers

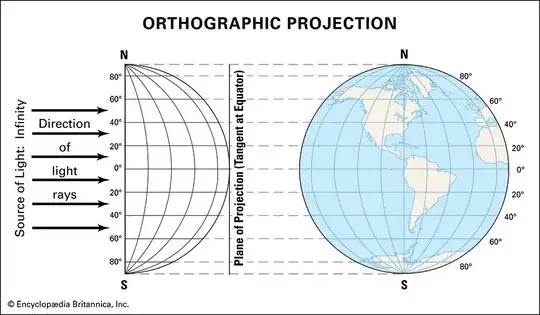

Your confusion may be partly the fault of the Britannica Kids online encyclopedia, assuming that's where you got this image.

This is not, repeat not, an orthographic projection:

I hope this example of an "orthographic" projection will be corrected on a future version of that page. The projection found there now, like the one in the question, appears similar to a portion of a Mollweide projection obtained by erasing everything at longitudes more than $90$ degrees from the central meridian of the map. That is, it looks like the map you get by inscribing a circular disk in a Mollweide projection as shown below and cutting away everything outside the disk.

It's hard to tell whether the spacing between latitudes is the same in the false "orthographic" projection and the Mollweide projection, however. The projection in Britannica Kids may not be any kind of standard projection at all.

Here is an orthographic projection:

Notice that the features near the middle of the projection look much larger than they do in the false "orthographic" projection. That's because in the center of the projection, you're looking straight down on the surface of the Earth and you see it in full size. Near the edges of the projection, you're looking at the surface of the Earth at a very small angle and although technically you see every point on the surface, features such as Greenland, Antarctica, Spain, western Africa and Alaska are compressed so that they look much smaller than they really are (and have very different shapes).

So the orthographic projection shows you half the surface of the Earth, but it does so at the expense of showing everything near the edge of the projection in a highly compressed and distorted way in order to fit it in. By doing this compression and distortion, it is able to squeeze an image of half the surface of the Earth into a region whose area is one quarter the area of the Earth, the same region you see when you look at a shadow of the Earth.

In summary, there is no difference in the size of the image whether you see the features of the surface or not. You see a disk of area one quarter the area of the sphere either way.

The commentary below assumes we actually are looking at part of a Mollweide projection in the figure falsely labeled "orthographic projection."

Like most map projections, the Mollweide projection is not any kind of projection you can get by shining a light from some point, even infinitely far away. You could instead think of it as a way of cutting the surface of the Earth along one line of longitude and distorting it to flatten it on a plane. You end up with an ellipse whose long axis is twice as long as its short axis.

If the height of the resulting map is $\sqrt2$ times the diameter of the Earth, the map will have the exact same area as the Earth's surface. But obviously you don't get an object with $\sqrt2$ times the diameter of the Earth by taking an orthographic projection. You have to "spread" the map quite a bit outside the orthographic image to cover that much area.

- 108,155

-

1Your red correction made my day lol. I still feel lingering confusion though (may be more a physics problem) as to why with my eyes, from outer space, I see half the INFORMATION of a sphere (albeit highly distorted and compressed at the edges, say Greenland), whereas a shadow at the same viewing location is only a quarter of the information of that sphere. Can you see how I'm led to start conjecturing that I must be some sort of higher-dimensional being, or that my vision has some sort of doubling power over shadows? Light of the same area as a shadow carries double the information? – Svenn Nov 10 '24 at 18:27

-

5The shadow actually has a lot less information. It tells you that all of the Earth is inside the cone of vision delimited by a certain disk. It tells you nothing about what any part of the surface of the Earth looks like. On the other hand, suppose you actually went out in space and took a color photograph of the Earth, then came home and had the photo printed on photographic paper. That image of Earth might have about $10^{-16}$ times as much area as the part of the Earth that you saw from space, but it would give you a lot more than $10^{-16}$ as much information as your eye saw. – David K Nov 10 '24 at 19:05

If you had a circular disk of fabric the area of the projection of the sphere you could not spread it to cover the half of the sphere that you see when you look at it, even accounting for (area-preserving) stretches to get the fabric to conform to the surface. The fabric near the edges of the patch must cover more area near the edges of what you see since what you see there on the sphere is foreshortened.

(A very small circular patch will almost cover a very small patch on the sphere.)

- 103,433

-

7I had no idea what was confusing the OP until I read this answer, which allowed me to see both the initial confusion and its resolution. – Cheerful Parsnip Nov 09 '24 at 21:45

The area of its shadow is the area of the disk bounded by the equator (with the simplifying assumption that the Earth is spherical). So imagine slicing a ball in half, like splitting an orange to share equally with a friend. Would you expect the area of the (newly created) cut surface to equal the area of the hemispherical exterior?

- 2,622

-

While the other answers are no doubt quite useful and insightful, this extremely lucid explanation gave words to the answer I intuitively had but could not reason aloud. – Ishan Manchanda Nov 11 '24 at 10:35

Consider the simpler example of an isosceles right triangle in 2D space. From an angle perpendicular to one of the legs, the hypotenuse would appear to have the same length as a leg, even though it does not. Its actual "surface area" in this case would be $\sqrt{2}$ times larger than its "shadow".

This should help show that straight-line projection generally isn't a length-preserving operation, so we shouldn't expect it to be an area-preserving one either.

- 329

-

2So perhaps am I confusing/conflating 'seen area' vs 'measured area'? The 'shadow area' is restricted to a 2d ruler STUCK on the shadow's own plane, whereas my vision is a sort of cubic 3rd ruler? I get double the information from the sphere by looking at the sphere, than the quarter information I get by looking at the shadow? I know I'm missing something basic here, thanks – Svenn Nov 09 '24 at 20:20

Take a regular piece of paper, and look at it edge-on, so that it's an infinitely thin line from your point of view.

Next, tweak its position the tiniest bit. You will be able to see all of the surface of one of the sides of the piece of paper, but its image in your field of view will be a very narrow strip, with a very small area.

Conclusion: If you have a surface with an intrinsic surface area of $S$, any projection* of it will have area $\le S$, and the less head-on your line-of-sight is to the surface, the greater the reduction of area.

In your case you have to do an integral over the hemisphere to deal with the fact that angle your line-of-sight makes with the surface varies from point to point over the hemisphere, but it's the same principle.

*"Projection" here means in the linear sense, like casting a shadow, or the way three-dimensional reality projects onto your two-dimensional field of view. Other answers have pointed out that the term "projection" is applied in map making to a much more general set of transformations, which may do all sorts of wacky distortions of area.

- 12,727

The fact that you can see (nearly) half the area when you look at a globe doesn't mean that the measure of the image formed on your retina is also half the area (adjusted for scale). Yes, you can visually observe the features present on up to half the area, but, if you consider your visual field to be akin to a flat screen, then the flat disk that is the image of the globe does not have the same area as the curved, hemispherical surface that it came from - its area is smaller.

As you move away from the center, you increasingly see the sides of the sphere at an angle. Any given small chunk of the surface when seen at an angle will take up a smaller area in your visual field compared to when seen head on (as you approach the sides, this area tends to zero).

So, the sphere you see is very much like the projected shadow, it's just that there are details (outlines of the continents, etc.) in the interior. Similarly, the shadow's surface area is the area of a flat disk - bordered by the projected outline of the sphere. And if the globe was transparent, say made out of glass, with just the outlines of the continents, the shadow would show both sides of the globe overlapping (so, the entire surface would be represented), but the disk of the shadow would still have the same area as before.

If you scale the area of the projection/shadow (that being $\pi r^{2}$) at each point of the shadow by the determinant of the Jacobian matrix describing the projection at that point, integrating over all such points, then you will get the surface area of the projected portion of the sphere (that being $2 \pi r^{2}$).

In vector calculus (the study of vector fields or mappings to multi-dimensional codomains), the Jacobian matrix is analogous to the derivative from univariate/"standard" calculus, or the gradient from multivariate calculus (the study of scalar fields). It describes the linear transformation that approximates the main transformation in the neighbourhood of the point in the domain that is being considered. Accordingly, its determinant (often just called "the Jacobian") describes the scale factor by which the transformation expands or compresses area in the neighbourhood of a given point.

The actual exercise directly computing this integral is a bit laborious, since it actually involves computing three Jacobians and integrals in order to be palatable (the first mapping 3D Cartesian coordinates to the projected portion of the sphere in spherical coordinates, the second mapping those spherical coordinates to the projection in polar coordinates, and the third mapping that projection in polar coordinates to the same projection in 2D Cartesian coordinates), but is a standard undergraduate exercise.

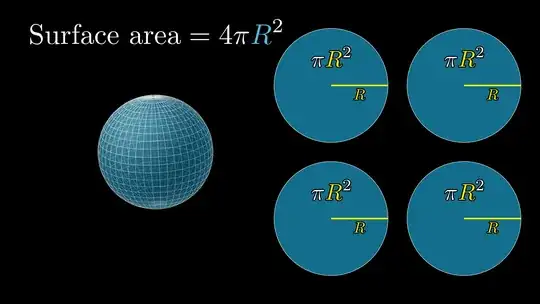

The 3Blue1Brown video that your second screenshot comes from actually uses the concept of the Jacobian in its first proof, but it doesn't refer to it by name. The demonstration that infinitesimal segments of the sphere can be mapped to infinitesimal segments of a corresponding cylinder relies upon the fact that the areas of the corresponding segments are equal. In other words, the Jacobian of the transformation from sphere to cylinder equals 1 everywhere, so the corresponding areas are equal. It side-steps the sequence of three transformations described above by instead noticing that there is another transformation we could consider (cylinder to sphere), whose original area we already know and can easily compute (that being the surface area of the cylinder).

- 290

These answers are much longer than necessary. The surface area of a sphere is 4πr² The area of a circle is πr² The ratio of the area of the circular shadow of the earth to the surface area of the sphere of the earth is πr²/4πr² = 1/4