Let's take a general 2nd-order recurrence relation with constant coefficients without a free term:

$$

a_{n+2} = ca_{n+1} + da_n

$$

The following polynomial is called a characteristic polynomial of the relation:

$$

x^2 - cx - d

$$

The importance of such polynomial lies in the following theorem:

$$

\forall x\ (x^2 - cx-d=0) \Rightarrow \forall n\ x^{n+2} = cx^{n+1} + dx^n

$$

Proof: $cx^{n+1}+dx^n = x^n(cx+d) = x^nx^2 = x^{n+2}$

Thus, by solving the characteristic polynomial, you can get solutions for respective recurrence relation (if $x_1, x_2$ - roots of the polynomial, then sequences $\{x_1^n\}_n^\infty$ and $\{x_2^n\}_n^\infty$ satisfy the relation).

It is easy to show, that any linear combination of sequences, satisfying the recurrence relation, also satisfies the relation:

$$

\forall a_n, b_n\ (a_{n+2} = ca_{n+1} + da_n) \wedge (b_{n+2} = cb_{n+1} + db_n) \Rightarrow \forall k, l\ ka_{n+2} + lb_{n+2} = k(ca_{n+1} + da_n) + l(cb_{n+1} + db_n) = c(ka_{n+1} + lb_{n+1}) + d(ka_n + b_n)

$$

So, if $x_1$ and $x_2$ are the roots of the characteristic polynomial, then for any $k, l$ sequence $kx_1^n + lx_2^n$ satisfies the relation, but we need to find such coefficients, that the starting conditions ($a_0, a_1$) are also satisfied. You could find them by solving the following system of linear equations:

$$

\cases{kx_1^0 +lx_2^0 = a_0\\kx_1^1+lx_2^1 = a_1}

$$

Observe, that if $x_1$ and $x_2$ are distinct, then the system always has a unique solution, as the respective matrix is not degenerate:

$$

\left|\array{x_1^0 & x_2^0\\x_1^1 & x_2^1}\right| = \left|\array{1 & 1\\x_1 & x_2}\right| = x_2 - x_1 \ne 0

$$

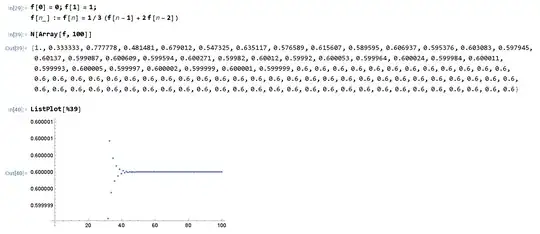

In your case, $x_1 = 1, x_2 = -\dfrac23, k = \dfrac35, l = -\dfrac35, a_n = \dfrac35\cdot1^n - \dfrac35 \cdot \left(-\dfrac23\right)^n = -\dfrac35\cdot \left(-\dfrac23\right)^n + \dfrac35, \lim_{n\to\infty}a_n = \dfrac35$.

In more general case, given a recurrence relation with constant coefficients

$$

a_{n+r} = c_1a_{n+r - 1} + ... + c_ra_n

$$

with characteristic polynomial

$$

(x-x_1)^{p_1}\cdot...\cdot(x-x_s)^{p_s}, \sum_{i=1}^s p_i = r, x_i \text{ are distinct}

$$

the following $r$ sequences satisfy the relation:

$$

x_1^n,\ nx_1^n,\ n^2x_1^n,\ ...,\ n^{p_1-1}x_1^n,\ x_2^n,\ ...,\ n^{p_2-1}x_2^n,\ ...,\ x_s^n,\ ...,\ n^{p_s-1}x_s^n

$$

and there is a unique linear combination of these sequences, that satisfies the relation and the starting conditions.

It is also possible to use this method, when a free term is present

$$

a_{n+r} = c_1a_{n+r - 1} + ... + c_ra_n + f

$$

by substituting $n$ with $n+1$ and subtracting the original relation:

$$

a_{n+r} = c_1a_{n+r - 1} + ... + c_ra_n + f \Rightarrow \cases{a_{n+r} = c_1a_{n+r - 1} + ... + c_ra_n + f\\a_{n+r+1} = c_1a_{n+r} + ... + c_ra_{n+1} + f} \Rightarrow\\\Rightarrow \cases{0 = -a_{n+r}+ c_1a_{n+r - 1} + ... + c_ra_n + f\\a_{n+r+1} = c_1a_{n+r} + ... + c_ra_{n+1} + f} \Rightarrow\\\Rightarrow a_{n+r+1} = (c_1+1)a_{n+r} + (c_2-c_1)a_{n+r-1} +...+ (c_r-c_{r-1})a_{n+1} - c_ra_n

$$

This way we get rid of the free term, but increase the order of the relation. To solve it with the method above, you need to update the starting conditions by calculating $a_r$.