I want to know the reasoning why the auxiliary function is in such form.

A couple examples:

On the OpenStax website there is a Calculus Volume 2 book. The proof of Taylor's theorem with remainder in Lagrange form can be found here: Chapter 6.3, Theorem 6.7. The auxiliary function used there is as follows:

$$ \ g(t) = f(x) - f(t) - f'(t)(x - t) - \frac{f''(t)}{2!}(x - t)^2 - \cdots - \frac{f^{(n)}(t)}{n!}(x - t)^n - R_n(x)\frac{(x - t)^{n+1}}{(x - a)^{n+1}}. \ $$

We are fixing $x$ here, right? And as I understand it, the $\frac{(x - t)^{n+1}}{(x - a)^{n+1}}$ part scales the $R_n(x)$ error term as $t$ changes. But why don't we fix $t$? I mean, we are expanding the Taylor series around $t$, so why should $t$ change? It doesn't make sense to me. I see that when $t = x$, the error term vanishes, and when $t = a$, we get the single $R_n(x)$ term. But isn't the point around which we are performing the expansion supposed to be fixed?

I also tried sketching it:

and I don't understand why the error term should vanish at $t = x$, because the divergence there should be significant. And at $t = a$ there is no error at all.

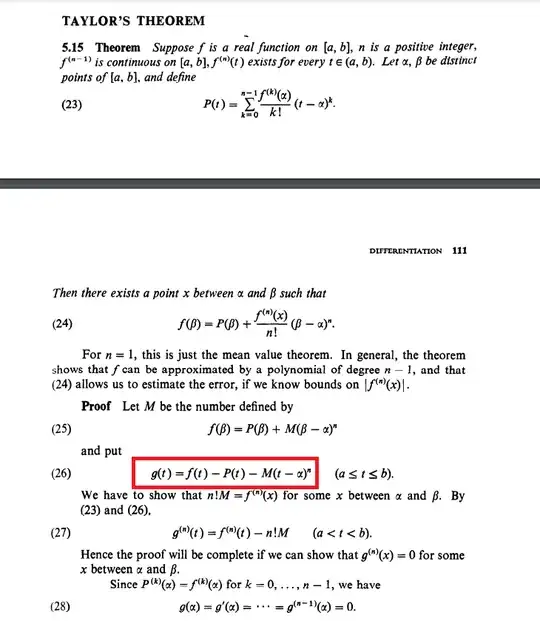

Principles of Mathematical Analysis by Walter Rudin p.111. The auxiliary function $g(t)$ looks like this:

In Rudin's book, he introduced an error term as "M(t - b)^n", which is not an obvious move at all, and the best "justification" I've seen is "this term is carefully chosen". And all I can think is "oh, carefully chosen, really?".

For example proof of Lagrange's Mean Value Theorem uses auxiliary function:

$$ F(x) = f(x) - \left[ \frac{f(b) - f(a)}{b - a} (x - a) + f(a) \right] $$

But it didn't come out of nowhere. The point is that to construct this function, we subtract from some function $f(x)$, the secant passing through two points on $f(x)$ and since they are equal at two points, their difference is zero at these two points. That's it, you can use Rolle's theorem. However, I did not come to it myself, but watched a video lesson.

And there is no magic. Whereas in the OpenStax Calculus book, the auxiliary function for Taylor's theorem proof, looks like it's pulled from a hat.

I have absolutely no idea what hat and what magic these functions were pulled out of.

No matter what article, video lecture, or book I find, nowhere does it explain where this function comes from. I want to understand the reasoning that could lead to this function. Without any reasoning, the appearance of this function seems like this: "A mathematician was sitting, handwaving and thinking, and suddenly decided that they wanted the function to be like this, and voilà, this function suddenly worked".

It even seems that those who learn math are either not expected to understand this detail, or the author of the article or video lecture doesn't know where it came from and just borrowed a "classical proof" to use in their material.

The proofs themselves (the ones mentioned above) weren't very hard to understand, but this particular gap makes any proof feel "artificial". I'm learning math on my own in my spare time (I don't have access to a teacher or professor), using open resources. However, I haven't been able to find any justification or "proof" for these functions, which has led to frustration.

Maybe there really isn't supposed to be a proof for them? How do mathematicians come up with such "functions pulled from a hat"?