Show that an ansatz is solving $\Delta|u|^{\frac12}=0$ in 2 dimensions $(\mathbb{R}^{1+1})$

I have added how the ansatz solve the equation by brute force, but I am stuck in defining properly it's boundary conditions, I don't know if it is even possible or not. I hope you could show me how if it is possible, or show why it is not.

Initial question

I am trying to extend the results of this other ODE question into it's PDE version.

So I would like to know if the following ansatz

$$u(x,t) = \frac{\text{sgn}(u(0,0))}{4}\left(2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}-(x+t)\right)^2\cdot\theta\!\left(2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}-(x+t)\right)$$

is a solution to

$$\Delta|u|^{\frac12}=0$$

I am trying this ansatz after realizing in Wolfram-Alpha that the solutions for $y'=-\sqrt{y}$ shown here have the same structure than the solutions for $\partial_t^2\sqrt{y}=0$ as shown here, and by using some ansatz with variable $(x+t)$ I am aiming to have some separation of variables (I hope).

I tried in Wolfram-Alpha and kind of solve it: it shows that $\partial_x^2\sqrt{u}+\partial_t^2\sqrt{u}=0$, but I moved the unitary step functions $\theta$ outside the derivatives and maybe it is illegal on this case (I aim to have cancellations of the form $(T-t)\delta(T-t)=0$). And I have no clue what to do with the initial/boundary conditions.

What would happen if I make the change of variable $\tau=-t$? Would it be solving $u_\tau=\Delta|u|^{\frac12}$? or maybe $(\partial_x^2-\partial_t^2)u^{\frac12}=0$?

and if it is not, which PDE these ansatz are solving?

And how I should define the initial/boundary conditions?

Hope you could show your steps, and comment about why it has lost a degree of freedom (the solution is determined by just one boundary, neither derivatives' initial conditions are required).

PS: I suspect the initial condition is ill defined since should be like $u(0,t)$ or something like that. Please fix it as it makes sense as PDE in the best way you need to fit the equations as solutions.

Update 4 - some attempts

The ansatz is based in what I reviewed for ODEs like $y'=-\sqrt[n]{y}$ in this answer which admits solutions of the form $y(t)=\left(\frac{(n-1)}{n}\left(T-t\right)\right)^{\frac{n}{n-1}}\theta(T-t)$ which becomes zero $y(t)=0,\,\forall t\geq T$ after some finite time $T<\infty$, and have the property of cancelling the derivatives of $\theta$ since $x\delta(x)=0$.

Thinking in the fact that finite duration behavior cannot be modeled by any non-piecewise power series since it would violate the Identity theorem, so classic ansatz with power series won't work here, and also that no linear ODE would show these behavior neither because a Non-Lipschitz term is required (details in these papers by Vardia T. Haimo paper 1 paper 2), since this question I wonder if for ODEs something like $x(t)=\sum\limits_{k=2}^\infty a_k(T-t)^k\theta(T-t)$ could be a general finite duration solution (notice is not a Taylor's series since is not defined at $t=T$, and the serie starts from $k=2$ because a constant term at $k=0$ would lead to Dirac's Delta functions on its derivatives, and $a_1=0$ such as $x'(T)=0$), but later I found that for PDEs the requirement of having a Non-Lipschitz term maybe don't apply since it is possible for linear PDEs to have solutions that becomes zero if I fix one point in space: see $\text{Eq. 8}$ and $\text{Eq. 9}$ in this question where a smooth bump function solves the classic wave equation in $\mathbb{R}^{1+1}$ (which are not even analytic), but I think that for becoming zero in the whole space of the variables $\{x,\ t\}$ it still required the non-Lipschitz term as shown in $\text{Eq. 11}$, but little analysis I could made from it since I don't know the Fourier Transform of a smooth bump function.

So looking for a simpler example where I could apply similar for the ODEs examples, I think about the Laplace's equation $\Delta u = 0$ since it could be solved by separation of variables. So I started to look for an ansatz for $\Delta|u|^{\frac12}=0$ thinking in a quadratic polynomial such the 2nd derivative of its square root were some constant (I could just added/sustract them later modifying the equation).

By substitution $n=2\,$ I have that $y'=-\sqrt{y}\,$ it is solved by $y(t)=\frac14(T-t)^2\theta(T-t)$. Now understanding that the trivial zero solution solves $\Delta|u|^{\frac12}=0$ I will forget about the term from $\theta(T-t)$ so I will focus only in the interval where the solution is not forever-zero and its derivatives don't participate in the results.

Then, thinking in the separation of variables of the Laplace's equation, I will try an ansatz $u(x,t)=y(x+t)$ and check if it will solve each second derivative $\partial_t^2 u=0$ and $\partial_x^2 u=0$.

- If I try to solve in Wolfram-Alpha $$\partial_x^2 u(x,t)=0$$ it is expanded as $$\frac{2uu_{xx}-u_x^2}{4u^{\frac32}}=0$$ and gives as solution $$u(x,t)=\frac{c_1(t)x^2}{4c_2(t)}+xc_1(t)+c_2(t)$$ which is the solution of matching the numerator equal to zero $$2uu_{xx}-u_x^2=0$$

- By symmetry I expect a similar quadratic answer on the time variable as shown in Wolfram-Alpha$$\partial_t^2 u(x,t)=0$$ it is expanded as $$\frac{2uu_{tt}-u_t^2}{4u^{\frac32}}=0$$ and gives as solution $$u(x,t)=\frac{c_1(x)t^2}{4c_2(x)}+tc_1(x)+c_2(x)$$ which is the solution of matching the numerator equal to zero $$2uu_{tt}-u_t^2=0$$

- So far a quadratic solution looks as the valid alternative, so thinking in the $\theta(T-t)$ derivatives cancellation requirement let review how they will behave: $$\begin{array}{r c l} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2}\left(\sqrt{\frac14(T-(t+x))^2}\right) & = & 0\qquad\text{as intended}\\ \frac{\partial^2}{\partial t^2}\left(\sqrt{\frac14(T-(t+x))^2}\right) & = & 0\qquad\text{as intended}\\ \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2}\left(\frac14(T-(t+x))^2\right) & = & \frac12\\ \frac{\partial^2}{\partial t^2}\left(\frac14(T-(t+x))^2\right) & = & \frac12\\ \end{array}$$ so the second derivatives are giving some constant value as expected, and solving the equation in particular due the linearity of the Laplacian operator.

- Now to verify if separation of variables is working lets check in Wolfram-Alpha the full equation: $$\partial_x^2 u(x,t)+\partial_t^2 u(x,t)=0$$ it don't gives a solution but do gives the following expansion $$\frac{2u(u_{xx}+u_{tt})-u_x^2-u_t^2}{4u^{\frac32}}=0$$ where you could notice is the sum of the previous results for each term considered independently. If I try to solve the numerator in Wolfram-Alpha it again don't deliver an solution $$2u(u_{xx}+u_{tt})-u_x^2-u_t^2=0$$ but I could do the following ansatz: if I believe a quadratic function is a solution, then the term of the double derivatives should match a constant value, let say $b$, so if I replace $u_{xx}+u_{tt}=b$ in Wolfram-Alpha I will have that $$2bu-u_x^2-u_t^2=0$$ do show as solution a quadratic function for the remaining equation, so is consistent the ansatz with the PDE I aiming to solve $$u(x,t) = \frac{2bc_1tx+2bc_2t+bc_1x^2+2bc_1c_2x+bc_2^2+bt^2}{2(c_1^2+1)}$$ now, if I make $b=\frac12+\frac12=1$ I will have $$u(x,t) = \frac{2c_1tx+2c_2t+c_1x^2+2c_1c_2x+c_2^2+t^2}{2(c_1^2+1)}=\frac{(c_2+t)^2+c_1x(2(c_2+t)+x)}{2(c_1^2+1)}$$ and if I set $c_1=1$ I will recover the form $$u_0(x,t) = \frac14(c_2+t+x)^2 =\frac14(c_3-(t+x))^2 $$ showing that at least the ansatz is consistent with the differential equation and separation of variables is working.

My problem now is in how to define properly boundary conditions: I don't know if its possible to make them with just one constant value, Do I require a smart choice? Or requiring just a constant shows the ansatz is not a valid solution of the PDE?

I am very rusty on boundary conditions problems, and here looks like one side is predetermined since it becomes zero loosing in this way a degree of freedom (I believe). In Wikipedia says the Laplace's Equation could be a specific form for a particular Heat Equation at steady-state, I remember seeing this equation in engineering a decade ago so I will review my notes and see if I can extrapolate something later.

But I hope someone could derive a formal solution during the bounty and not my ugly trial-and-error procedure.

Update 5

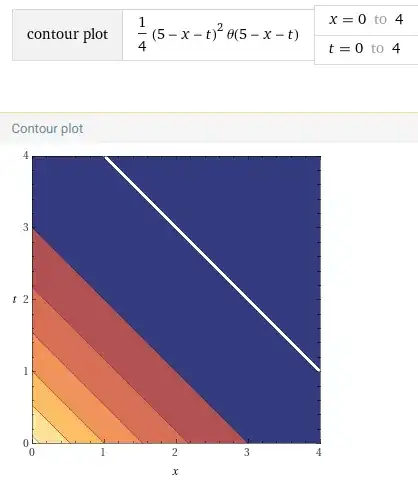

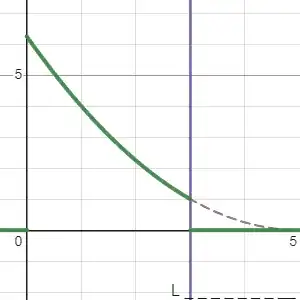

I have tried some things I saw for solving the heat equation but don't work, I think it lost all their flexibility in the way I did the ansatz and only a determined shape for the boundaries are allowed. Fixing $T=5$ I have these plots of a quadratic function that decreases to zero as time passes: Contour plot / Desmos plot

I still think it is a valid solution, the value at $x=L$ would be $u(L,t)=\frac{1}{4}\left((2\sqrt{u(0,0)}-L-t)^{+}\right)^2$.

Hope you could confirm if this is formally a valid solution.

From now on it is not a mandatory reading for giving an answer

Update 1 - answers to comments

User @K.defaoite have made some interesting observations and it would extend too much the comments so I will answer here with more detail what I have done so far.

I aim to make a simple case of a PDE with solutions of finite duration, and started from something I know it already show these kind of behavior: the ODE shown in the mentioned question is given by: $$u'(t) = -\text{sgn}(u(t))\sqrt{|u(t)|}$$ will stand the solution: $$u(t) = \frac{\text{sgn}(u(0))}{4}\left(2\sqrt{|u(0)|}-t\right)^2\cdot\theta\!\left(2\sqrt{|u(0)|}-t\right)$$ where the finite extinction time $T=2\sqrt{|u(0)|}<\infty$ the solution by itself would become zero forever after. Notice this behavior cannot be modeled by any non-piecewise power series since it would violate the Identity theorem, so classic ansatz with power series won't work here. Also, no linear ODE could have these kind of solutions of finite duration, since the require a Non-Lipschitz term in the ODE when uniqueness could be broken (details in these papers by Vardia T. Haimo paper 1 paper 2).

As studied in this other question, an analogous phenomena for PDEs is not as easy to understand: in Eq. 8 and Eq. 9 I could make a linear PDE that show a solution of finite duration if I focus only in one point in space, but since solutions to PDEs aren't lines as in ODEs, but instead, like surfaces/sheets, and these sheets never become zero on the full $\{t,x\}$ space, I tried to force this behavior and I was able to make a PDE in Eq. 11 that do show the PDE-kind of finite duration behavior, but unfortunately, the solution I used is based in an smooth bump function so I cannot use the Fourier Transform to study is properties (but I do can do it in the case of the mentioned ODE solution as is shown here).

Later thanks to the following comment by @CalvinKhor he tells than in this paper is shown that the PDE $u_t=\Delta u^m,\,0<m<1$ is shown to support these kind of solutions of finite duration. Unfortunately the math level of the paper overpass my current skills (I understood very little of the paper), but since the example looks similar to the one I did above, I am trying to make with it the simplest posible example of a closed-form solution of finite duration to a PDE.

What I did is the following: since I am thinking in only 2 dimensions, one for time and other for space $\mathbb{R}^{1+1}$, in this case $\Delta \equiv \partial_t^2+\partial_x^2$ and the most simple equation would be just making it equal to zero, this is why I based the question in $\Delta|u|^{\frac12}=0$ instead of the mentioned one $u_t=\Delta u^{\frac12}$, but any example would work for me.

I tried first the following analogy with the wave equation: if I have a phase variable $\varphi = x-t$, the wave equation $u_{tt}=u_{xx}$ it could be transformed just in $u_{\varphi\varphi}=u_{\varphi\varphi}$ and recover the wave equation by expanding the LHS by time and the RHS by the space variable. So I tried to insert just a similar variable $\varphi = x\pm t$ on the solution of the ODE to see what would happen.

From now on, I start to do some illegal stuff to see what will happen and how it would fail hoping to take lessons in order to improve further attempts. The first non-rigorous assumption was keeping the initial condition as a constant $u(0,0)$ which I think is mistaken since PDEs requires boundary conditions, but to check what would happen with the change of variable $\varphi$ it would be a first approach to keep it as constant.

Then I starting by trying replacing $u(x,t):=u(\varphi_1)$ with $\varphi_1 = x+t$ and taking the second derivatives, but with an illegal step that was moving outside the derivative the step function for avoiding Dirac's delta functions, something that sometimes could be done as explained in this comment by @md2perpe, but I am not sure if here it is valid or not. Also, other illegal thing, I will focus first only in scenarios where $u(x,t)\geq 0$ since I could avoid the absolute value and evaluate $\Delta u^{\frac12}$ instead of $\Delta |u|^{\frac12}$, with all these I found the following on the answers of Wolfram-Alpha 1 and Wolfram-Alpha 2:

$$\begin{array}{r c l} \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2}\left(\sqrt{\frac{\text{sgn}(u(0,0))}{4}\left(2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}-(x+t)\right)^2 }\right) & = & 0 \\ \dfrac{\partial^2}{\partial t^2}\left(\sqrt{\frac{\text{sgn}(u(0,0))}{4}\left(2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}-(x+t)\right)^2 }\right) & = & 0 \\ \end{array}$$

and this gives me hopes that maybe it is possible to improve it for solving $\Delta |u|^{\frac12}=0$ or maybe $(\partial_x^2-\partial_t^2)|u|^{\frac12}=0$, but I don't know how to proceed with the boundary conditions, my PDEs background is only on linear PDEs through Fourier solution and that kind of approach don't works here (and to be honest, it is very rusty).

I hope now is more clear what I am trying to do. I don't know how to explain it further.

Update 3 - answer 2 to @K.defaoite comments

If I focus on the equation $u_t=\Delta |u|^{\frac12}$ in the RHS I will have the same situation described in the Answer 1 of $\Delta |u|^{\frac12} = 0$, and in the LHS following Wolfram-Alpha I will have:

$$\begin{array}{r c l} \dfrac{\partial}{\partial t}\left(\sqrt{\frac{\text{sgn}(u(0,0))}{4}\left(2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}-(x+t)\right)^2 }\right) & = & -\frac12\sqrt{\text{sgn}\!(u(0,0))}\,\text{sgn}\!\left(2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}-(x+t)\right) \end{array}$$

And here I fall again in the issues with the border conditions I don't know how to handle:

- If I choose $u(0,0)=0$ the equation is solved but don't have any meaning since it becomes the trivial zero solution for $t\geq 0$

- Now if I try to make $u(0,0)$ such as $2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}-(x+t)=0$ then it would be a function of $\{x,\ t\}$ and all previous derivatives are invalid since $u(0,0)$ is not a constant anymore but instead something like $u(0,t)$ or $u(x,0)$ which will make pop-up some extra terms.

The alternative could be make that $2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}-(x+t)>0$ with already $u(0,0)>0$ on the whole interval the solutions is just different from zero, which will make become: $$u_t\equiv -\frac12$$

So instead I should be trying to solve the differential equation: $$u_t+\frac12 = \Delta |u|^{\frac12}$$

or maybe try an ansatz $v(x,t) = u(x,t)+\frac{t}{2}$ for the equation $v_t = \Delta |v|^{\frac12}$ instead.

But since I don't fully understand the problem of how to define initial/border conditions on non-linear PDEs I could be making many other alternatives and all we have the same validity that these ones: none, since I don't even now if they are ill defined from they very beginning.

That is why I am looking for a simple example, for having something to grab and start from there. Hope you could give one, what ever you want, with a simple finite duration solution.

Update 2: answer to comment to @AlexRavsky

With $\varphi = x-t$ you get:

$$\begin{array}{r c l}\text{RHS:}\quad u_{\varphi\varphi} & = & \frac{\partial}{\partial\varphi}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial\varphi}\right) = \frac{\partial}{\partial\varphi}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial\varphi}\underbrace{\frac{\partial x}{\partial x}}_{=1}\right) = \frac{\partial}{\partial\varphi}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial x}\frac{\partial x}{\partial \varphi}\right) = \frac{\partial}{\partial\varphi}\left(\frac{u_x}{\left(\underbrace{\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}}_{=1}\right)}\right) \\ & = & \frac{\partial}{\partial\varphi}\left(u_x\right)\underbrace{\frac{\partial x}{\partial x}}_{=1} = \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(u_x\right)\frac{\partial x}{\partial \varphi} = u_{xx}\left(\underbrace{\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial x}}_{=1}\right)^{-1} = u_{xx}\end{array}$$

$$\begin{array}{r c l}\text{LHS:}\quad u_{\varphi\varphi} & = & \frac{\partial}{\partial\varphi}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial\varphi}\right) = \frac{\partial}{\partial\varphi}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial\varphi}\underbrace{\frac{\partial t}{\partial t}}_{=1}\right) = \frac{\partial}{\partial\varphi}\left(\frac{\partial u}{\partial t}\frac{\partial t}{\partial \varphi}\right) = \frac{\partial}{\partial\varphi}\left(\frac{u_t}{\left(\underbrace{\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial t}}_{=-1}\right)}\right) \\ & = & -\frac{\partial}{\partial\varphi}\left(u_t\right)\underbrace{\frac{\partial t}{\partial t}}_{=1} = -\frac{\partial}{\partial t}\left(u_t\right)\frac{\partial t}{\partial \varphi} = -u_{tt}\left(\underbrace{\frac{\partial \varphi}{\partial t}}_{=-1}\right)^{-1} = u_{tt}\end{array}$$

$$\Rightarrow u_{\varphi\varphi}=u_{\varphi\varphi} \iff u_{xx}=u_{tt} \iff u_{xx}-u_{tt}=0\quad\text{wave equation in 2D with }c=1$$

Update 6 - comments to @CalvinKhor answer

Thanks for the answer. This is going to be too long for the comment section, but in summary I would like you to elaborate on "non-zero harmonic functions cannot be identically zero on any non-empty open set".

In the intro section of the Wiki for Harmonic functions they are defined as an "harmonic function is a twice continuously differentiable function $f:\,U\to\mathbb{R}$, where $U$ is an open subset of $\mathbb{R}^n$ that satisfies Laplace's equation", so in mi mind (maybe mistakenly), all what I need is to prove it satisfies the Laplace's equation (which I think I did en Update 4).

So far i was able to understand from your answer, considering $T:=2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}$, far away the critical line $L:= T-(x+t)=0$ there are no issues since the trivial zero solution $u_0(x,t)=0$ solves the Laplace's equation, and on the other section, assuming now $u(0,0)>0$, then $q(x,t)=\sqrt{u(x,t)}=\frac12 |T-(x-t)|$ should be fulfilling the Laplace's equation far away of the critical line $L$ (Wolfram-Alpha): $$\frac{\partial^2}{\partial \{x^2,\ t^2\}}\left(q(x,t)\right)=\delta(T-(x-t))$$ so it is zero outside the critical line $L$ fulfilling the Laplace's equation.

So the problem is to see what happens in the critical line $L$: but here it is fulfilling already that $T-(x+t)=0$ which implies that $$u(x,t)\biggr|_{L}= \frac{\text{sgn}(u(0,0))}{4}\left(\overbrace{\require{cancel}\cancel{2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}-(x+t)}}^{\displaystyle{=0}}\right)^2\cdot\theta\!\left(2\sqrt{|u(0,0)|}-(x+t)\right)\equiv 0$$ so it shouldn't be any problems here neither since we are again taking derivatives of the trivial zero solution.

$$\Delta|u|^{\frac12} = \begin{cases} 0,\quad \text{if}\,\, T-(x+t)>0 \,\,\text{since}\,\, \frac{\partial^2}{\partial \{x^2,\ t^2\}}\left(\sqrt{u(x,t)}\right)=\delta(T-(x-t)) \\ 0,\quad\text{if}\,\, T-(x+t)=0 \,\,\text{since}\,\, u(x,t)=0\\ 0,\quad\text{if}\,\, T-(x+t)<0 \,\,\text{since}\,\, \theta(T-(x+t))=0\\\end{cases}$$ which looks continuous for me (maybe I am mistaken here, please also elaborate about this).

With these points in mind I think $u(x,t)$ it is indeed exactly solving the $\Delta|u|^{\frac12}=0$, so it is being harmonic in the Wikipedia's definition sense.

But here it is where I would like you to elaborate on the answer you shared: If I think about non-piecewise power series, like the polynomial solution mentioned in the comment by @paulgarrett, it would never become a constant flat value due the Identity theorem, so in this non-piecewise sense I understand I wouldn't have harmonic solutions.

But because of this, I would like to know if the mentioned reasons you based you answer are assuming as axiom the solution must be non-piecewise defined, since for the piecewise definition I have used, for me looks like it is exactly solving the $\Delta|u|^{\frac12}=0$ equation, and as example of what I meaning here, the Liouville's theorem (complex analysis) is based in a Entire function, which, as also the Maximum modulus principle, has as assumption that the studied function is an Holomorphic function, so it starts from the assumption that the studied function it is Analytic function, so they have both been built with the underlying assumption that the studied function could be represented by a non-piecewise power series on the whole domain it is defined, assumption that the function $u(x,t)$ don't fulfills to start with, and I am wonder if the same issue it is happening with the analysis you have shared (here maybe I am mistaken and had a conceptual mistake, so this could be an important point for me to understand).

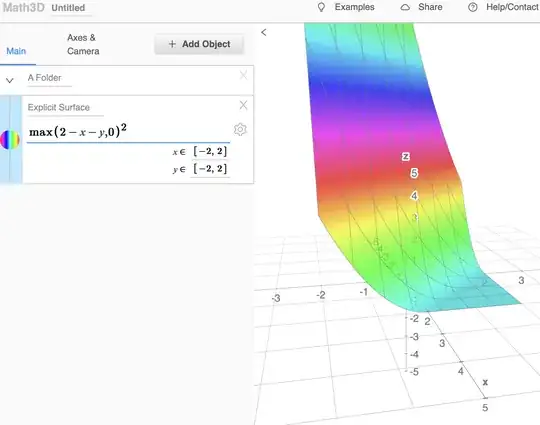

PS: I was not aware about the Math3D website, thanks for sharing it!.