When introduced to limits in school, we are told that the limit of a function $f(x)$ as $x$ tends to $x_0$, if it exists, is a specific value that the function tends towards as $x$ tends to a specific value, $x_0$, from the right and from the left. This is accompanied by examples where we put really close values to $x_0$ into our calculator and convince ourselves that the function really does tend to this value from both sides.

In college, we are then told that this can be formalised using the $\epsilon$-$\delta$ definition, with little reference to what was previously known about them. The college definition starts by defining $\epsilon$, which bounds the outputs of a function within an interval about the limit. The outputs of the function should not go beyond this first bound. Then it goes on to say that there is some $\delta$, which bounds the arguments of the function within an interval about $x_0$. The inputs of the function should not go beyond this second bound. It then goes on to say that the outputs for this second bound should lie within the interval of the allowable outputs of the first bound.

The first approach is to get close to $x_0$ and see if the outputs get close to some value we call the limit. The second approach is to bound the outputs and say we can always bound the inputs so that their output is within the originally set bounds for the output.

Why do we abandon the school version? Is the school version even able to be formalised? If it can be, why is this formalisation not shown; is there any relationship between the two perspectives, and are they even different perspectives?

What follows is my attempt at answering the second question: formalising the school version.

The version taught in school starts with some very small $\delta>0$. You put that into your calculator, get an even smaller $\delta>0$, put that into your calculator, and you can see the function approximating some value. So, we are analysing $f(x\pm \delta)$. We can put conditions on the function based on whether the monotonicity of the function is increasing, decreasing or just constant from the left or right. This is based on the observation that if we were to plot inputs against outputs, from our calculations, we would hope to see a curve or line that gets close to or is a limit.

In other words, we are analysing the function to see if it behaves a certain way for small values of $\delta$. To get a limit, you don't concern yourself with how the function looks beyond this small $\delta$ but within this small $\delta$. And within this small $\delta$, the function must behave a certain way. So the choice of $\delta$ depends on the function behaving a certain way. If we have that the function behaves a certain way around the value we want to approach, then we can find the limit. If we can't find a region where the function behaves a certain way, then we can't find the limit. Now, this certain way is where the function from both the left and right is increasing, decreasing or constant. And so we need to know what inputs about $x_0$ on either side give unique monotonicities in $f(x)$.

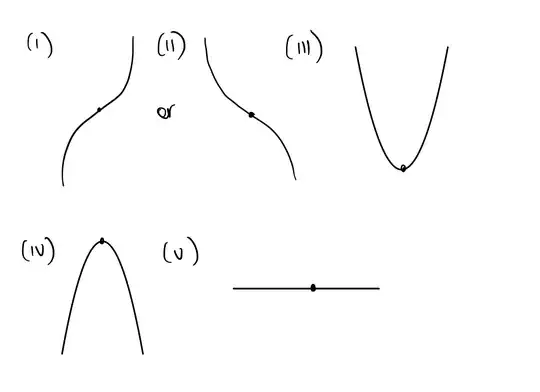

The limit $\lim_{x \rightarrow x_0}f(x)$ is the unique value that satisfies the following conditions, which are that for every $\delta > 0$, $$\ \left|\lim_{x \rightarrow x_0}f(x) \right|< f(x_0 \pm \delta) \tag {I}$$ or $$\ \left|\lim_{x \rightarrow x_0}f(x) \right|> f(x_0 \pm \delta) \tag{II}$$ or $$\ 2\lim_{x \rightarrow x_0}f(x)-f(x_0 - \delta) < \lim_{x \rightarrow x_0}f(x) < f(x_0 + \delta) \tag{III}$$ or $$\ 2\lim_{x \rightarrow x_0}f(x)-f(x_0 - \delta) > \lim_{x \rightarrow x_0}f(x) > f(x_0 + \delta) \tag{IV}$$ or $$\ f(x_0 - \delta)=\lim_{x \rightarrow x_0}f(x)=f(x_0 + \delta). \tag{V}$$

The graphs correspond to the cases I am considering for the limit definition, with $x$-$y$ axis treated as usual. For $(\text{III})$ and $(\text{IV})$, I flipped the half of the function left of the limit so they would be in the form for cases $(\text{I})$ and $(\text{II})$.

Thanks!

Edit: I somehow missed the questions directly similar to mine. Links: Does the epsilon-delta definition of limits truly capture our intuitive understanding of limits?, specifically this answer on Math SE is helpful if it is true. This answer seems related to non-standard analysis here.