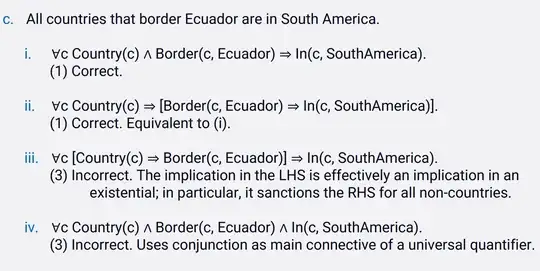

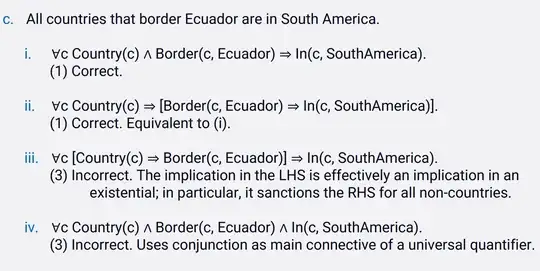

I know that part (iii) kinda says that if C is a country then it borders Ecuador

No, (iii) doesn't assert that ∀c (Country(c) ⟹ Border(c,Ecuador)), since (iii) is (vacuously) true if this assertion is false!

that is, "for every C, if that is a country, then it borders Ecuador, then it is in SouthAmerica."

Your translation is ungrammatical, and ambiguous, since between (A ⟹ B) ⟹ C and A ⟹ (B ⟹ C) and (A ⟹ B) and (B ⟹ C), there is no equivalent pair. A literal translation of (iii) is

- If a thing borders Ecuador if it's a country, then it's in South America. ✅

This translation is hard to accurately understand, and most people will just misread it as (i)/(ii) , that is, as

- if a thing is a country that borders Ecuador, then it's in South America ❌

- if a country borders Ecuador, then it's in South America. ❌

Fortunately, its (logically equivalent) contrapositive is much friendlier to parse:

- If a thing isn't in South America, then it's a country that doesn't border Ecuador. ✅

Incidentally, do observe that (iii) implies, ludicrously, that every balloon is in South America.

I want to know whether there is a method to convert "and ($\land$)" to implication; this way, parts (i) and (ii) are interchangeable.

A useful equivalence to remember:$$A ⟹ (B ⟹ C) \quad\equiv\quad (A ∧ B) ⟹ C.$$ Convince yourself of it by first considering the left-to-right entailment, then considering the right-to-left entailment.

On a tangential note: your textbook's omission of the outermost parentheses in its four sample logic statements isn't optimal practice, because for example $$\forall x\, Px\Longrightarrow Q\quad\equiv\quad (\forall x\, Px)\Longrightarrow Q\quad\equiv\quad \exists x\,( Px\Longrightarrow Q) \quad\not\equiv\quad \forall x\, \color\red(Px\Longrightarrow Q\color\red).$$