This answer generalizes the question.

Call the sum $S$ for the case asked. Consider a tuple $(a,b) \in \mathbb N^2$ where $1\le a,b\le n$. Consider some $r \in [1,n] \cap \mathbb N$. For how many tuples $(a,b)$ is $\min(a,b) = r$? You can construct exactly $(n-r+1)^2 - (n-r)^2$ such tuples$^{*}$. Thus the sum is just

$$\begin{align}

S &= \sum_{r=1}^{n} r((n-r+1)^2 - (n-r)^2) \\

&= \sum_{r=1}^{n} r(n-r+1)^2 - \sum_{r=1}^{n} r(n-r)^2 \\

&= \sum_{r=1}^{n} r(n-r+1)^2 - \sum_{\color{red}{r=0}}^{n} r(n-r)^2\\

&= \sum_{r=1}^n (n-r+1)r^2 - \sum_{r=0}^n (n-r)r^2\tag{1.1}\\

&= \sum_{r=1}^n (n-r+1)r^2 - \sum_{\color{red}{r=1}}^n (n-r)r^2\\

&= \sum_{r=1}^n r^2

\end{align}$$

REMARKS:

$^{*}$: the most important aspect of the solution is counting the number of tuples where $\min(a,b)=r$ is obeyed. To count them first count all the tuples where $(a,b) \in \{r,r+1,r+2,\dots, n\}^2$ and then subtract all tuples where $(a,b) \in \{r+1,r+2,r+2, \dots, n\}^2$. This counts all tuples where $\min(a,b) \geq r$ and then subtracts all tuples where $\min(a,b)\geq r+1$.

$(1.1)$ uses the fact that $\sum_{r=a}^{n} f(r) = \sum_{r=a}^n f(n-r+a)$. This is called reversing the order of the sum.

I provide two bonuses;

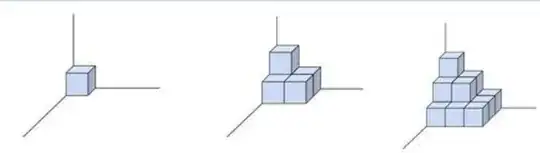

Claim $1$: $S_1(k,n) = \underset{1\le x_1,x_2,x_3,\dots,x_k \le n}{\sum} \min(x_1,x_2,x_3,\dots, x_k) =\sum_{r=1}^n r^k$

Setting $k=2$ in this case yields the desired identity asked in the question.

Proof: Consider all $k$-tuples $\in \mathbb N^k$ where all their elements are in $[1,n]$. There are exactly $(n-r+1)^k - (n-k)^k$ such $k$-tuples which have their minimum element some fixed $r$. Since $r\in [1,n] \cap \mathbb N$ we have

$$\begin{align}

S_1(k,n) &= \sum_{r=1}^n r((n-r+1)^k - (n-r)^k) \\

&= \sum_{r=1}^{n} (n-r+1)(r)^k - \sum_{r=1}^n (n-r)(r)^k \\

&= \boxed{\sum_{r=1}^n r^k}

\end{align}$$

Claim $2$: $S_2(k,n) = \underset{1\le x_1,x_2,x_3,\dots,x_k \le n}{\sum} \max(x_1,x_2,x_3,\dots, x_k) =n^{k+1} - \sum_{r=1}^{n-1} r^k$

Proof: As usual, there are exactly $r^k - (r-1)^k$ $k$-tuples such that the tuple's maximal element is some $r\in[1,n]\cap \mathbb N$ where the $k$-tuples are $\in \mathbb N^k$ where each element $\in [1,n]$. Thus

$$\begin{align}

S_2(k,n) &= \sum_{r=1}^n r(r^k - (r-1)^k)\\

&= n^{k+1}+\sum_{r=1}^{n-1}r^{k+1} - \sum_{r=1}^{n-1}(r+1)r^k\\

&= \boxed{n^{k+1}-\sum_{r=1}^{n-1} r^k}

\end{align}$$