I want to show that $S^1$ is diffeomorphic to $\mathbb{RP}^1$ (where $S^1$ is the unit circle). But I don't understand how. I have a hint to use the function $f : S^1 \to S^1$, $f(z) = z^2$.

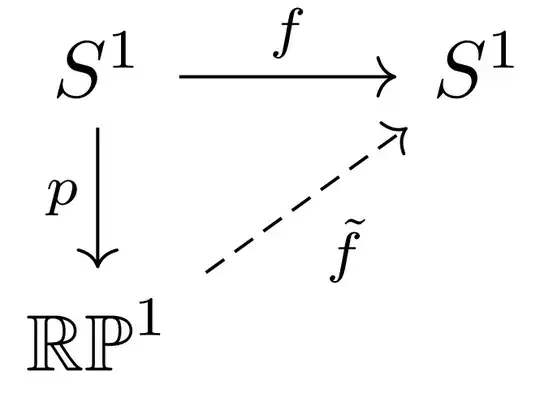

So, because $\mathbb{RP}^1 = S^1/\sim$, where $x \sim y \iff x = \pm y$, we will have something like this:

In this diagram $p$ is the projection map on quotient space. So, $\tilde{f} : \mathbb{RP}^1 \to S^1$ defined by $\tilde{f}([z]) = z^2$ is a homeomorphism. Now that's all I know. How can I proceed to show that $\tilde{f}$ is a differentiable map? Thanks!

- 16,972

- 1,396

-

The diagram here may be of interest. – Andrew D. Hwang Sep 08 '24 at 23:51

3 Answers

There is a very general property concerning when maps out of the quotient are smooth.

Theorem.

Let $X,Y,Z$ be smooth manifolds, $\pi:X\to Y$ a smooth surjective submersion, and let $f:Y\to Z$ any map. Then, $f$ is smooth if and only if $f\circ\pi$ is.

(Draw a triangular commutative diagram).

If $f$ is smooth, then clearly so is $f\circ\pi$.

Proof #1 of the converse. Let $n:=\dim X,m:=\dim Y$. Fix a point $y_0\in Y$ and consider any point $x_0\in\pi^{-1}(\{y_0\})$ (such a point exists since $\pi$ is surjective). The local submersion theorem now tells us we can find charts $(U,\alpha)$ for $X$ around $x_0$ and $(V,\beta)$ for $Y$ around $y_0$ such that $\alpha[U]$ contains $\{0_{\Bbb{R}^{n-m}}\}\times\beta[V]$ and $\beta\circ\pi\circ\alpha^{-1}$ is (the restriction to $\alpha[U]$ of) the projection $\Bbb{R}^n\cong \Bbb{R}^{n-m}\times\Bbb{R}^m\to\Bbb{R}^m$, i.e locally $\pi$ is the projection onto the last $m$ coordinates. Now, for $y\in \beta[V]$, we have \begin{align} (f\circ\beta^{-1})(y)&=(f\circ\beta^{-1})(\text{pr}(0,y))=(f\circ (\pi\circ\alpha^{-1}))(0,y)=((f\circ \pi)\circ\alpha^{-1})(0,y). \end{align} Since $f\circ\pi$ is smooth and so is $\alpha$, it follows this is clearly a smooth function of $y$. Therefore, $f|_V=(f\circ\beta^{-1})\circ\beta$ is smooth on $V$. Since the point $y_0$ was arbitrary, it follows $f$ is smooth on $Y$.

Proof #2 of the converse. It’s essentially the same idea: using the local submersion theorem, once can show that $\pi$ has smooth local sections (use $\alpha,\beta$ as above, and observe that $s(y):=(0,y)$ is a section of $\text{pr}=\beta\circ\pi\circ\alpha^{-1}$, and hence $\sigma:=\alpha^{-1}\circ s\circ\beta$ is a local section of $\pi$). With this general useful fact out of the way, fix any point $y_0\in Y$ and a smooth local section $\sigma$ of $\pi$ in some neighbourhood $V$ of $y_0$. Then, $f|_V=f\circ \text{id}_V= f\circ(\pi\circ\sigma)=(f\circ\pi)\circ\sigma$, which is a composition of the smooth map $f\circ\pi$ with $\sigma$, hence $f|_V$ is smooth. Since $y_0$ was arbitrary, it follows again that $f$ is smooth on $Y$.

Corollary (Descending to the Quotient).

Let $X,Y,Z$ be smooth manifolds, $\pi:X\to Y$ a smooth surjective submersion and $f:X\to Z$ a smooth map which is constant on the fibers of $\pi$. Then, $f$ descends to a unique smooth map $\tilde{f}:Y\to Z$ such that $f=\tilde{f}\circ \pi$.

(Let me remark that a smooth surjective submersion is also a quotient map between the underlying topological spaces, so we view $Y$ as a quotient of $X$).

The fact that $f$ is constant on the fibers of $\pi$ implies by basic set theory that it descends to a unique map $\tilde{f}$ such that a suitable diagram commutes (i.e $f=\tilde{f}\circ\pi$). The theorem above now tells us $\tilde{f}$ is in fact smooth (please excuse my different usage of $f$ in the theorem vs corollary), thus proving the corollary.

We can indeed apply this corollary, because the map $p:S^1\to\Bbb{RP}^1$ is indeed a smooth surjective submersion (even better, it forms a fiber bundle with typical fiber $\Bbb{Z}_2$… i.e is a smooth $2$-fold covering space), it follows that $\tilde{f}$ is also smooth.

The way you can prove this mapping $\tilde{f}$ is a diffeomorphism is by first ‘flipping your diagram’: $\require{AMScd}$ \begin{CD} S^1@>{p}>> \Bbb{RP}^1 \\ @V{f}VV \\ S^1 \end{CD} Show that $p$ descends to a map $\tilde{p}:S^1\to\Bbb{RP}^1$ making the diagram comute (it is essentially $\tilde{p}(z):=p(\sqrt{z})$ (why does it not matter which square root we take?)); this $\tilde{p}$ is smooth by the corollary. Then, check that $\tilde{p}$ and $\tilde{f}$ are inverses, and thus $\tilde{f}$ is a diffeomorphism.

This last bit btw is a special case of a more general instance of ‘uniqueness of quotients’:

Uniqueness of Smooth Quotients.

Let $X$ be a smooth manifold, and for $i\in\{1,2\}$, let $\pi_i:X\to Q_i$ be smooth surjective submersions. Suppose that $\pi_1$ and $\pi_2$ ‘make the same identifications’, i.e are constant on each others’ fibers, or equivalently induce the same equivalence relations on $X$: $\mathcal{R}_{\pi_1}=\mathcal{R}_{\pi_2}$, where \begin{align} \mathcal{R}_{\pi_i}:=\{(x_1,x_2)\in X\times X\,:\, \pi_i(x_1)=\pi_i(x_2)\}. \end{align}

Then, there is a unique diffeomorphism $\phi:Q_1\to Q_2$ such that $\pi_2=\phi\circ\pi_1$ (i.e a certain diagram commutes).

Finally, I will mention that in the particular case of the circle, it is possible to explicitly write out all the local sections (it’s essentially a branch of the square root) without needing the local submersion theorem (i.e the inverse/implicit function theorem). You can directly verify that your map $\tilde{f}$ is a bijection, and pick a suitable collection of charts (you need only a small number in this case) then check the corresponding transition maps are smooth. This is the type of approach taken in other answers on the site, for instance Showing diffeomorphism between $S^1 \subset \mathbb{R}^2$ and $\mathbb{RP}^1$.

I presented the above reasoning so that you get accustomed to dealing with quotients more generally (e.g when trying to prove $\Bbb{CP}^1\cong S^2$, or that various definitions of the circle (a sa submanifold of $\Bbb{R}^2$ or more abstractly as $\Bbb{R}/\Bbb{Z}$) or torus ($(S^1)^n$ or $\Bbb{R}^n/\Bbb{Z}^n$) or real projective spaces ($\Bbb{S}^n$ modulo antipodal identification vs $\Bbb{R}^{n+1}\setminus\{0\}$ modulo the dilation action of $\Bbb{R}\setminus\{0\}$) are equivalent).

- 65,833

I will give a more down to earth answer than peek-a-boo's as I believe it introduces machinery you may not yet be familiar with.

Note that we have smooth charts which cover $S^1$ given by: \begin{align} \phi_{N}:U_N&\longrightarrow \mathbb R\smallsetminus 0\\ z&\longmapsto \frac{Re(z)}{1-Im(z)}\\ \phi_S:U_S&\longrightarrow \mathbb R\smallsetminus 0\\ z&\longmapsto \frac{Re(z)}{1+Im(z)} \end{align} where $U_N=S^1\smallsetminus \{Im(z)=1\}$, and $U_S=S^1\smallsetminus\{Im(z)=-1\}$. We have inverse charts for $\mathbb {RP}^1$ given by: \begin{align} \psi_1^{-1}:\mathbb R^1\smallsetminus\{0\}&\longrightarrow V_1\\ x&\longmapsto \left[\frac{i(x-i)^2)}{1+x^2}\right]\\ \psi_2^{-1}:\mathbb R^1\smallsetminus\{0\}&\longrightarrow V_2\\ x&\longmapsto \left[\frac{(x+i)^2}{1+x^2}\right]\\ \end{align} where $V_1=\{[z]\in \mathbb {RP}^1:Re(z)\neq 0\}$, $V_2=\{[z]\in \mathbb {RP}^1:Im(z)\neq 0\}$.

I will check that $\tilde{f}$ is smooth in one case, and leave the rest to you. \begin{align} \phi_{N}\circ \tilde{f}\circ \psi_1^{-1}(x)=\phi_{N}\left(\frac{-(x-i)^4}{(x^2+1)^2}\right) \end{align} Now: \begin{align} Re(z)=\frac{6x^2-x^4-1}{(x^2+1)^2}\qquad \text{and}\qquad Im(z)=\frac{4x^3-4x}{(1+x)^2} \end{align} Putting these together we obtain that: \begin{align} \phi_N\left(\frac{-(x-i)^4}{(x^2+1)^2}\right)=\frac{6x^2-x^4-1}{(1+x^2)^2-4x^3+4x} \end{align} Now note that this smooth so (supposing the same holds true for all such coordinate charts) $\tilde{f}$ is smooth. Now note that the derivative of this composition is given by: \begin{align} (\phi_{N}\circ \tilde{f}\circ \psi_1^{-1})'=\frac{4(1+x^2)}{(x^2-2x-1)^2} \end{align} which is nowhere zero, hence $D_x\phi_{N}\circ \tilde{f}\circ \psi_1^{-1}$ is an invertible linear map for all $x$. Supposing this holds for the other chart combtinations, we have that since the differentials of the coordinate charts are invertible, $D_{[z]}\tilde{f}$ must be an isomorphism for all $[z]\in \mathbb{RP}^1$. It follows by the inverse function theorem that since $\tilde{f}$ is bijective (as op has pointed out), $\tilde{f}$ is a diffeomorphism as desired.

- 5,420

-

1Last sentence you should mention that $\tilde{f}$ is bijective; otherwise the statement is not true (granted, OP knows this map is a homeomorphism, but still) – peek-a-boo Sep 02 '24 at 02:54

-

-

-

Shouldn't be $\psi_1^{-1}(x) = [1+ix]$ and $\psi_2^{-1}(x) = [x + i]$? – ProofSeeker Sep 02 '24 at 23:25

-

Well if your taking $\mathbb{RP}^1$ to be $S^1/\sim$ it makes sense to essentially take the inverse chart $\mathbb{R}^1\smallsetminus 0\rightarrow S^1\smallsetminus{z_0}\subset \mathbb C$. Obviously it doesn't matter because of the equivalent equivalence relations, but this is the cleanest way to set it up for this diffeomorphism. As a note, there are many compatible charts for $\mathbb{RP}^1$, you just need a cover of them, and want to choose the right ones to suite your needs – Chris Sep 02 '24 at 23:46

-

To be in $S^1 \setminus {z_0}$ it shouldn't be $\left[\frac{x+i}{\sqrt{x^2+1}}\right]$ ? Or I don't think I understand – ProofSeeker Sep 03 '24 at 18:14

-

1@MathLearner You are right, I made a mistake in my inverse charts. It needed to be of the form I know have above. This made the calculations a bit harrier than I anticipated...but I might've also made a mistake somewhere. In particular, I think this sort of calculation could probably be made easier with a different choice of charts. Perhaps the stereographic projection but taking $\mathbb S^1\subset \mathbb R^2$, or the exponential charts $\theta\mapsto e^{i\theta}$. – Chris Sep 03 '24 at 19:53

We prove that both are homeomorphic to $[0,1]/ \{0=1 \}$ the quotient space of the interval by gluing the two ends. For $S^1$ we have the map $t\to e^{2i\pi t}$ does the job, for $RP^1$ the map $t\to {\bf R}e^{i\pi t}$ send the point $t$ to the line through the origin at the angle $\pi t$, and also does the job.

- 8,588