Yes, the expected volume can be given in closed form, with the help of a generalization of Sylvester's Four-Point Problem.

The general term for members of the series (point, line, triangle, tetrahedron, ...) is simplex. The volume of an n-simplex can be easily calculated from a determinant constructed from the coordinates of its vertices, divided by n factorial.

We can calculate the expected volume of a random n-simplex in a unit hypersphere via equation (3) from the linked MathWorld page. We also need the equation for the volume of the unit n-dimensional hypersphere:

$$V(n) = \frac{\pi^{n/2}}{\Gamma(n/2+1)}$$

where $\Gamma()$ is the gamma function. For all $z$, $$\Gamma(z+1) = z\Gamma(z)$$

For non-negative integer $n$,

$$\Gamma(n) = (n-1)!$$

and

$$\Gamma(n+\frac12) = \left(\frac{(2n)!}{4^n n!}

\right)\sqrt{\pi}$$

Note that $V(0)=1$.

The Sylvester equation uses the binomial coefficient, in particular, the generalized central binomial coefficient, which can be written in terms of the gamma function:

$$\binom{2n}{n} = \frac{\Gamma(2n+1)}{\Gamma(n+1)^2}$$

The equation for the expected simplex volume is:

$$S(n) = \frac{\dbinom{(n+1)}{(n+1)/2}^{n+1}}{2^n\dbinom{(n+1)^2}{(n+1)^2/2}} \frac{\pi^{n/2}}{\Gamma(n/2+1)}

$$

Here are the results for small $n$, computed using SageMath:

Exact expected volume

| n |

Expected volume |

| 0 |

$1$ |

| 1 |

$\frac{2}{3}$ |

| 2 |

$\frac{35}{48 \, \pi}$ |

| 3 |

$\frac{12}{715} \, \pi$ |

| 4 |

$\frac{676039}{7776000 \, \pi^{2}}$ |

| 5 |

$\frac{32000}{272254059} \, \pi^{2}$ |

| 6 |

$\frac{107492012277}{27536588800000 \, \pi^{3}}$ |

| 7 |

$\frac{21008750000}{56100739008446649} \, \pi^{3}$ |

| 8 |

$\frac{109701233401363445369}{1210054852352102400000000 \, \pi^{4}}$ |

| 9 |

$\frac{527046113468915712}{778482596802192849805651985} \, \pi^{4}$ |

To 6 significant figures

| n |

Expected volume |

| 0 |

1.00000 |

| 1 |

0.666667 |

| 2 |

0.232101 |

| 3 |

0.0527260 |

| 4 |

0.00880878 |

| 5 |

0.00116005 |

| 6 |

0.000125897 |

| 7 |

0.0000116113 |

| 8 |

9.30694e-7 |

| 9 |

6.59476e-8 |

Here's the Sage / Python script to do those calculations.

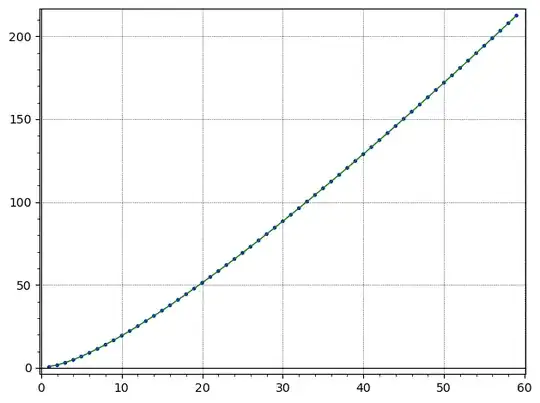

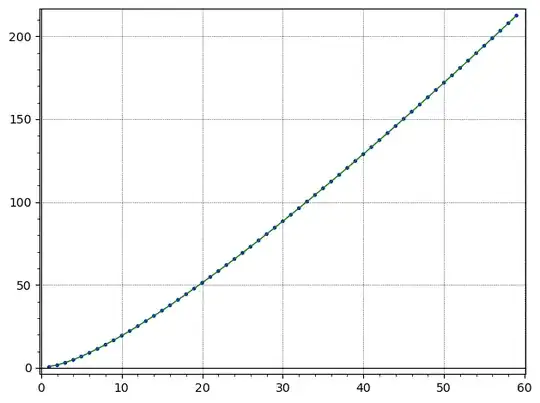

As $n\to\infty$,

$-\log(S(n))$ converges approximately to $$1.322365 - 0.5n + n\log(n)$$

It converges quite quickly. In this plot, the green curve is that function and the blue dots are $-\log(S(n))$.

Here's the plotting script.

Here's the plotting script.

Here's a Sage / Python script that computes the expected volume by random sampling using the technique given in https://stackoverflow.com/a/54544972/4014959 to generate the uniformly distributed points. The script generates ~500,000 points and then finds the mean of 100 partitions of simplexes formed from those points.