Let $r:y=mx+(-mx^\ast+y^\ast)$ be a generic line passing through the point $(x^\ast,y^\ast)\in \mathbb{R}^2$ and let $p(x)=\sum_{i=0}^n a_ix^i$ be a generic polynomial of degree $n$ (so $a_n\neq 0$). Clearly

$$r \ \ \text{is tangent to the graph of $p$}\iff \text{there is $x_0\in \mathbb{R}$ such that $\begin{cases} m(x_0-x^\ast)+y^\ast=p(x_0)\\ m=p'(x_0)\end{cases}$}$$

So

$$r \ \ \text{is tangent to the graph of $p$}\iff p'(x_0)(x_0-x^\ast)+y^\ast=p(x_0) \ \ \ \text{for some $x_0\in \mathbb{R}$}$$

So we have

$$r \ \ \text{is tangent to the graph of $p$}$$ $$ \iff$$ $$a_{n}(1-n)x_{0}^n+\sum_{i=1}^{n-1}(a_{i}-a_{i} i+x^\ast a_{i+1}(i+1))x_0^i+(a_0+x^\ast a_1-y^\ast)=0,\ \ \ \text{for some $x_0\in \mathbb{R}$}$$

Let $\mathcal{S}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}$ be the set of $x_0\in \mathbb{R}$ that solve the equation above and let $$\mathcal{T}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}:=\{p'(x_0):x_0\in \mathcal{S}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}\}.$$ I denote with $|\mathcal{S}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|$ and $|\mathcal{T}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|$ the cardinalities of these sets.

The number $|\mathcal{T}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|$ is the number of tangent lines passing through $(x^\ast,y^\ast)$.

The number $|\mathcal{S}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|$ is the number of tangent lines with their tangency multiplicities : basically each tangent line is counted once if it's tangent in just one point, twice if it's tangent in two points, thrice if it's tangent in three points and so on.

To see this subtlety consider the linear case $p(x)=a_1x+a_0$. Let $(x^\ast,y^\ast)$ be a point on the graph of $p$ (that is a line in this case). Clearly $|\mathcal{T}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|=1$ because there is just one tangent line (the line $p$ itself), but $|\mathcal{S}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|$ is infinite because the only tangent line is tangent in every point.

So here we have two questions:

How to calculate $|\mathcal{S}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|$?

How to calculate $|\mathcal{T}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|$?

The second one is very difficult so I'll ignore it. In this answer I'll focus on the first question (in most examples $|\mathcal{S}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|=|\mathcal{T}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|$).

Remember that $|\mathcal{S}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|$ is the number of real solutions of the following polynomial equation:

$$a_{n}(1-n)x^n+\sum_{i=1}^{n-1}(a_{i}-a_{i} i+x^\ast a_{i+1}(i+1))x^i+(a_0+x^\ast a_1-y^\ast)=0$$

For simplicity, I'll call the polynomial above $Q(x)$. If $n=1$, the situation is trivial so I'll suppose $n\geq 2$. If $n\geq 2$ then the polynomial $Q(x)$ has degree $n$ so it has at most $n$ solutions. We have our first result.

Proposition 1: $|\mathcal{S}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|\leq n$

This is compatible with your "experimental results". Moreover it's a well known fact that a polynomial of odd degree has at least a real root.

Proposition 2: $|\mathcal{S}_{(x^\ast,y^\ast)}|\geq 1$ if $n$ is odd.

This is completely compatible with your "experimental observation".

CONTINUATION OF THE ANSWER:

Let's discuss the low-degree cases i.e. $n\in \{1,2,3\}$.

n=1

As I said the case $n=1$ is trivial.

n=2

In this case:

$$Q(x)=-a_2x^2+2x^\ast a_2 x+(a_0+x^\ast a_1-y^\ast)$$

The number of zeroes of $Q$ depends on the sign of the discriminant $\Delta$. It's easy to see that

$$\Delta=0\iff y^\ast=Q(x^\ast)$$

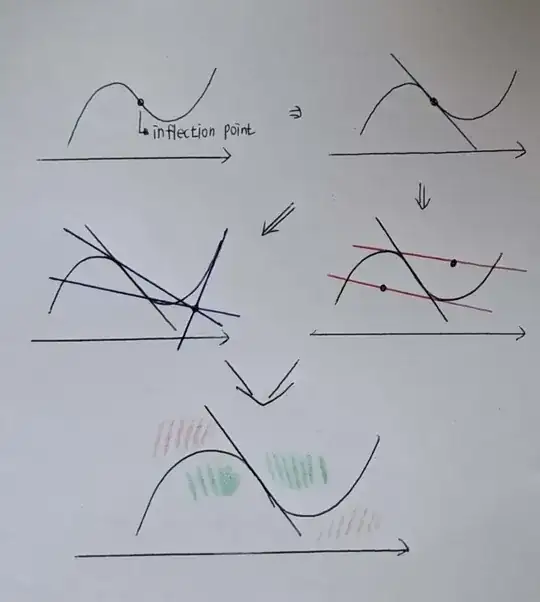

So the parabola $Q$ perfectly splits the plane in two part: one whose points have no tangent line and one whose points have two tangent lines and the points on the parabola have exactly a tangent line.

Curiosity: This result may seem an incredibly special property, but it holds not only for parabolas but for the graph of any $C^2$ function with second derivative of constant sign.

n=3

In this case

$$Q(x)=-2a_3x^3+(3x^\ast a_3-a_2)x^2+2x^\ast a_2 x+(a_0+x^\ast a_1-y^\ast)$$

Although it's not very well known, there is a discriminant also in the cubic equation

A cubic equation $$Ax^3+Bx^2+Cx+D=0$$ has three distinct real roots iff $$-27A^2D^2+18ABCD-4AC^3-4B^3D+B^2C^2>0$$

For simplicity , I'll denote the expression above $\Delta_3$. We have also that $\Delta_3=0$ iff there are $2$ distinct real roots and $\Delta_3<0$ iff there is just one real root.

For our polynomial $Q$ we have that (with an incredibly tedious computation)

$$\Delta_3=4 (p(x^\ast) - y^{\ast}) (9 a_3 a_2^2 x^\ast - 27 a_1 a_3^2 x^\ast + 27 a_3^2 y^{\ast} + a_2^3 - 27 a_0 a_3^2)$$

So basically the problem is completely controlled by the sign of the factors $(Q(x^\ast)-y^{\ast})$ an $(9 a_3 a_2^2 x^\ast - 27 a_1 a_3^2 x^\ast + 27 a_3^2 y^{\ast} + a_2^3 - 27 a_0 a_3^2)$. The sign of the first factors tells us whether $(x^\ast,y^\ast)$ is under or above the graph of our polynomial $p$. The sign of the second factors tells us if $(x^\ast,y^\ast)$ is under or above the following line

$$\ell: y=\left(-\frac{a_2^2}{a_3}+a_1\right)x-\frac{a_2^3}{27a_3^2}+a_0$$

Who is this mysterious line $\ell$? Exactly the tangent line at the inflection point that you cited in your question! (Do you know how to prove this?).

n=4

TO BE CONTINUED