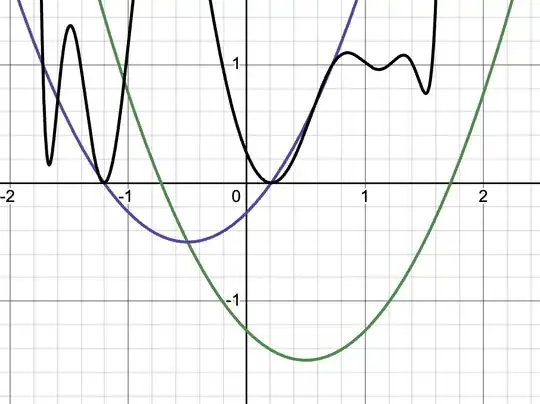

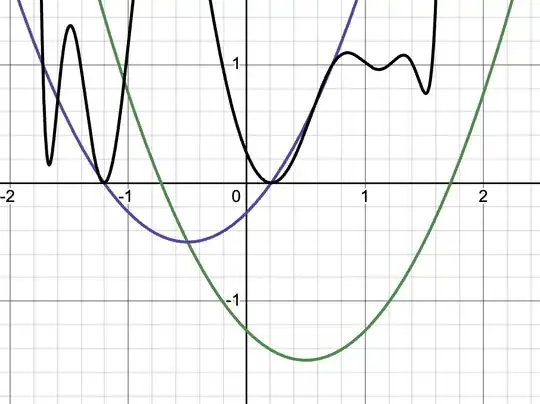

Edit: Here's a graph in Desmos where you can slide the value of $a$ around and see the root collisions at $a = -3$ and $a = -5$ really explicitly. This is what $a = -5$ looks like, where green is $f_1$, blue is $\frac{f_2}{f_1}$, and black is $\frac{f_4}{f_2}$:

Write $f_n = f^n(x) - x$ to save on notation. Everything I'm about to do is sloppy and likely could be cleaned up a lot. Also this is all probably somewhere in the literature on arithmetic dynamics.

The roots of $f_n$ are, by definition, $\lambda$ such that $f^n(\lambda) = \lambda$. So they are periodic with period dividing $n$ with respect to the action of $f$. That means they naturally divide up into different classes depending on their period: if $n = 4$ (I am going to focus on this case) they could have periods $1, 2$, or $4$, corresponding to which of $f_1, f_2, f_4$ they are roots of first, and this corresponds to a factorization

$$f_4 = f_1 \frac{f_2}{f_1} \frac{f_4}{f_2}$$

of $f_4$. This factors the discriminant into smaller discriminants and resultants

$$\Delta(f_4) = \Delta(f_1) \text{Res} \left( f_1, \frac{f_2}{f_1} \right)^2 \Delta \left( \frac{f_2}{f_1} \right) \text{Res} \left( f_1, \frac{f_4}{f_2} \right)^2 \text{Res} \left( f_2, \frac{f_4}{f_2} \right)^2 \Delta \left( \frac{f_4}{f_2} \right).$$

Alternately we can work diectly with the discriminant in terms of the product $\prod_{i \neq j} (\lambda_i - \lambda_j)$ over all pairwise differences of roots. These roots live in a finite Galois extension $L$ of the function field $\mathbb{Q}(a)$ (namely the splitting field of $f_n$), and are acted on in two different ways:

- By the Galois group $G = \text{Gal}(L/\mathbb{Q}(a))$; the orbits of this action factor the discriminant over $\mathbb{Q}(a)$.

- By $f$ itself; if $\lambda$ is a root then so is $f(\lambda)$, because $f$ sends periodic points to periodic points.

These actions commute, and they both preserve periods! This means the Galois group must contain and centralize $f$.

If $f(x)$ is quadratic then $f_4$ has degree $2^4 = 16$, so there are $16$ roots $\lambda_i$. They can have periods $1, 2, 4$, and there are $\deg f_1 = 2$ roots of period $1$, $\deg f_2 - \deg f_1$ roots of period $2$, and hence $12$ roots of period $4$. The $2$ roots of period $2$ organize themselves into a single $2$-cycle $\{ \lambda, f(\lambda) \}$ under the action of $f$, while the $12$ roots of period $4$ organize themselves into three $4$-cycles $\{ \lambda, f(\lambda), f^2(\lambda), f^3(\lambda) \}$ under the action of $f$.

$f_1$ and $\frac{f_2}{f_1}$ are both irreducible over $\mathbb{Q}(a)$, so the $2$ roots of period $1$ and the $2$ roots of period $2$ each form a single Galois orbit under the actions of the Galois group of $f_1$ and $\frac{f_2}{f_1}$ respectively. The Galois group of $\frac{f_4}{f_2}$ must contain $f$ acting with cycle decomposition $(4, 4, 4)$, and moreover the action of $f$ commutes with the rest of the Galois group, so the largest the Galois group could be is the wreath product $C_4 \wr S_3$, of order $4^3 \cdot 6$. This means the Galois group acts by permuting the three $4$-cycles and "rotating" each of them individually, although possibly not all such permutations occur.

Now let's analyze the orbits. Write $d(\lambda)$ for the period of $\lambda$ under the action of $f$. We have the following cases for the factors $\lambda_i - \lambda_j$ of the discriminant (of the full polynomial $f_4$ this time):

- $d(\lambda_i) = d(\lambda_j) = 1$. This case occurs twice and we get a single Galois orbit, corresponding to $\Delta(f_1) = - (a - 1)$.

- $d(\lambda_i) = 1, d(\lambda_j) = 2$ or the reverse. This case occurs $8$ times and we get two Galois orbits of size $4$, corresponding to $\text{Res}(\frac{f_2}{f_1}, f_1)^2 = (a + 3)^2$.

- $d(\lambda_i) = d(\lambda_j) = 2$. This case occurs twice and we get a single Galois orbit, corresponding to $\Delta(\frac{f_2}{f_1}) = - (a + 3)$. Together with the above calculation, this is the first example of something we haven't discussed at all, namely: why are there not only so many factors, but why are their multiplicities so high? In this case, why is this $a + 3$ the same as above? This one is easy to understand: what this factor means is that at $a = -3$ the two points of period $2$ have collided. But they have to be sent to each other under the action of $f$. So when they collide their period drops to $1$, and so they also must collide with one of the points of period $1$! And we can check this explicitly: when $a = -3$ the roots of $f_2$ are $\frac{3}{2}$ with multiplicity $1$, and $-\frac{1}{2}$ with multiplicity $3$.

- $d(\lambda_i) = 1, d(\lambda_j) = 4$ or the reverse. This case occurs $24$ times and we get two Galois orbits of size $12$, corresponding to $\text{Res}(\frac{f_4}{f_2}, f_1)^2 = (a^2 - 2a + 5)^2$. This tells us when a point of period $4$ collides with a point of period $1$. I think we get a nontrivial quadratic in $a$ here because this happens at two different values of $a$ depending on which point of period $1$ collides, and we should be able to check this by calculating the roots of $\frac{f_4}{f_2}$ at the two roots of $a^2 - 2a + 5$ and explicitly comparing them with the roots of $f_1$.

- $d(\lambda_i) = 2, d(\lambda_j) = 4$ or the reverse. This case occurs $24$ times and we get two Galois orbits of size $12$, corresponding to $\text{Res}(\frac{f_4}{f_2}, \frac{f_2}{f_1})^2 = (a + 5)^4$ (I think). This tells us when a point of period $4$ collides with a point of period $2$.

The final case $d(\lambda_i) = d(\lambda_j) = 4$ is the most interesting case and is complicated enough that we need to treat it separately. It occurs $12 \cdot 11 = 132$ times and has several Galois orbits, because the points of period $4$ organize into three $4$-cycles as we saw above, and the Galois group is sensitive to whether points are in the same cycle. This corresponds to $\Delta(\frac{f_4}{f_2})$ splitting into different factors, as follows.

- The "generic" case is that $\lambda_i$ and $\lambda_j$ are in different cycles; this case occurs $12 \cdot 8 = 96$ times and is a single Galois orbit. At a value of $a$ at which two points $\lambda_i, \lambda_j$ of period $4$ in different cycles have collided, the same must be true of the points $f(\lambda_i), f(\lambda_j)$, etc.; that is, the rest of the two cycles have also collided, so the discriminant vanishes to order $4$. However, no collisions with points of smaller period have been forced. So this factor of $\Delta(\frac{f_4}{f_2})$ must be the most complicated one, $(a^3 + 9a^2 + 27a + 135)^4$.

- Next, $\lambda_i$ and $\lambda_j$ could be in the same cycle. The next case is that $\lambda_j = f(\lambda_i)$ or $\lambda_j = f^3(\lambda_i)$, which occurs $24$ times and consists of two Galois orbits. At a value of $a$ at which two such roots collide, they become period $1$ and so must also collide with a root of period $1$. That means the corresponding factors of the discriminant must be a power of the factor $a^2 - 2a + 5$ we found in the $(1, 4)$ case above, so I am going to guess that this factor must be $(a^2 - 2a + 5)^3$, although I don't quite understand the multiplicity of $3$.

- The final case is that $\lambda_j = f^2(\lambda_i)$, which occurs $12$ times and is a single Galois orbit. At a value of $a$ at which two such roots collide, they become period $2$ and so must also collide with a root of period $2$. That means the corresponding factors of the discriminant must be a power of the factor $a + 5$ we found in the $(1, 4)$ case above and so must be the remaining factor $(a + 5)^2$.

So, overall this analysis revealed a lot of structure but in the end it turned out the Galois group didn't fully explain the high multiplicities of the factorization (really it only helps explain why $\Delta(\frac{f_4}{f_2})$ splits into three factors but not why their multiplicities are so high), and what we really needed to understand was 1) the behavior of the roots wrt $f$, and 2) the combinatorics of how two roots colliding at different values of $a$ forces other collisions depending on their behavior wrt $f$. Hopefully someone else can clean this up or knows a reference that does all this properly.

Also I might just be wrong about the Galois group and the real Galois group might be smaller, which would break up the factors further.