Notation

Let $[a, b] = [0, 1]$. Since we will be dealing with trees, let's recall some notation. The set of naturals numbers is $\omega$, each natural number consists of the preceding natural numbers: $n = \{ 0, \ldots, n-1 \}$. For $c \in \omega$,

$c^{\omega}$ is the set of infinite sequences over $\{ 0, \ldots, c-1 \}$,

$c^{<\omega} = \displaystyle \bigcup_{n < \omega} c^n$ is the set of all finite sequences over $\{ 0, \ldots, c-1 \}$.

Counterexample

Define $\nu : 3^{\omega} \to 3^{\omega}$ so that $\nu$ turns turns each $1$ into a $2$ and vice versa. Formally, $\nu(s) = \tau \circ s$, where $\tau = \binom{0 \ 1 \ 2}{0 \ 2 \ 1} \in S_3$. With a slight abuse of notation we let $\nu$ map $3^{<\omega}$ to $3^{<\omega}$ in the same fashion. Let $\mathcal{B} \subseteq [0, 1]$ denote a variant of the fat Cantor set and $\mathcal{C} \subseteq [0, 1]$ a variant of the ordinary Cantor set, so that both are naturally homeomorphic to $3^{\omega}$ (rather than $2^{\omega}$). Take the natural homeomorphisms $\varphi : \mathcal{B} \to 3^{\omega}$ and $\psi : 3^{\omega} \to \mathcal{C}$ and let $v = \psi \circ \nu \circ \varphi : \mathcal{B} \to \mathcal{C}$.

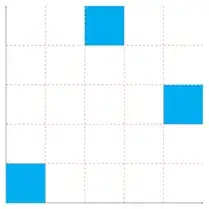

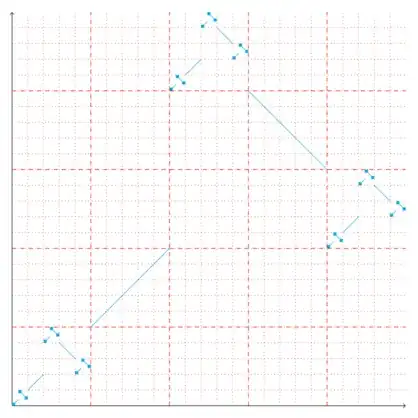

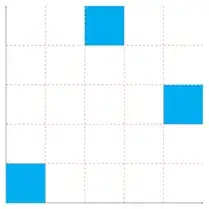

Schematically, the graph of $v$ is the intersection of an infinite sequence of sets, the first three of which are depicted below (the X axis is not to scale since we want a fat Cantor set there):

Clearly $v$ is injective. It is easy to see but cumbersome to prove that $v$ has bounded variation. Roughly, let $(I_{\eta})_{\eta \in 3^{<\omega}}$ and $(J_{\eta})_{\eta \in 3^{<\omega}}$ denote the tree of intervals used to construct $\mathcal{B}$ and $\mathcal{C}$, respectively, so that

$$\mathcal{B} = \bigcap_{n < \omega} \bigcup_{\eta \in 3^n} I_{\eta} \qquad \text{ and } \qquad \mathcal{C} = \bigcap_{n < \omega} \bigcup_{\eta \in 3^n} J_{\eta}.$$

Note that the length of $J_{\eta}$ is $\frac{1}{5^n}$ for any $\eta \in 3^n$. Since for any $x \in I_0$ and $y \in I_1$ we have $|v(y) - v(x)| \leqslant 1$ and likewise for $x \in I_1$, $y \in I_2$, we have that

$$V_{[0, 1]}(v) \leqslant V_{I_0}(v) + 1 + V_{I_1}(v) + 1 + V_{I_2}(v).$$

Arguing in the same way for $I_k$, $k \in \{ 0, 1, 2 \}$, we have

$$V_{I_k}(v) \leqslant V_{I_{k^{\frown}0}}(v) + \frac{1}{5} + V_{I_{k^{\frown}1}}(v) + \frac{1}{5}+ V_{I_{k^{\frown}2}}(v)$$

and so on. Since each finite subset of $[0, 1]$ from which we compute the variation will be completely separated by intervals $(I_{\eta})_{\eta \in 3^n}$ for sufficiently large $n$, we have

$$V_{[0, 1]}(v) \leqslant 2 + 3 \cdot \left( \frac{2}{5} + 3 \cdot \left( \frac{2}{25} + \ldots \right) \right) = \sum_{n=0}^{\infty} 2 \cdot \left( \frac{3}{5} \right)^n < \infty.$$

Now we extend $v$ to $u : [0, 1] \to [0, 1]$ in the following way. Given $\eta \in 3^{<\omega}$, we let $u$ map the open interval between $I_{\eta^{\frown}0}$ and $I_{\eta^{\frown}1}$ to the open interval between $J_{\nu(\eta)^{\frown}0}$ and $J_{\nu(\eta)^{\frown}1}$ as an increasing linear function. Similarly, we let $u$ map the open interval between $I_{\eta^{\frown}1}$ and $I_{\eta^{\frown}2}$ to the open interval between $J_{\nu(\eta)^{\frown}1}$ and $J_{\nu(\eta)^{\frown}2}$ as a decreasing linear function.

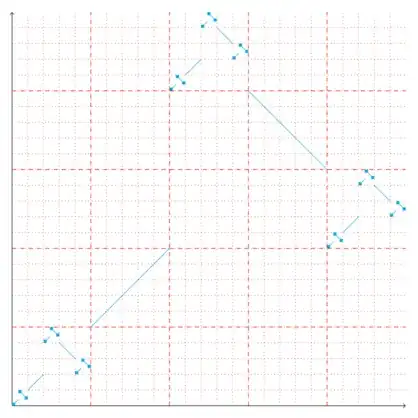

The result looks approximately as follows:

Clearly $u$ is a bijection and has the same variation as $v$. It remains to prove that there is no $u_0$ satisfying conditions (3) and (4). Assume for contradiction that some $u_0 : [0, 1] \to \mathbb{R}$ satisfies these conditions. Since $\lambda(N) = 0 < \lambda(\mathcal{B})$, one of the intervals $(a_k, b_k)$ must intersect $\mathcal{B}$. Then $(a_k, b_k)$ contains $I_{\eta}$ for some $\eta \in 3^{<\omega}$. Since all of $I_{\eta^{\frown}0}$, $I_{\eta^{\frown}1}$, $I_{\eta^{\frown}2}$ have positive measure, we can find their elements $x_0$, $x_1$, $x_2$, respectively, such that $u_0(x_k) = u(x_k)$ for $k = 0, 1, 2$. But then $u_0(x_0) < u_0(x_1) > u_0(x_2)$, contradicting the fact that $u_0$ is monotonic on $(a_k, b_k)$.