On P61 of Lax's Functional Analysis:

I'll type it out:

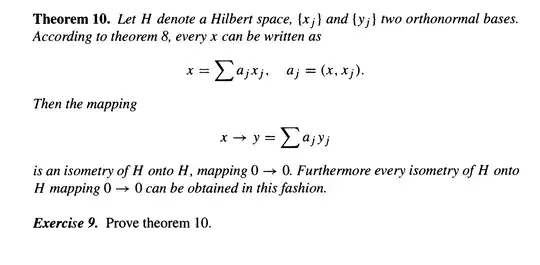

Let $H$ denote a Hilbert space, $\{x_j\}$ and $\{y_j\}$ two orthonormal bases. Every $x\in H$ can be written as $$x = \sum a_j x_j,\quad a_j = \langle x,x_j\rangle$$ Then the mapping $$x\to y = \sum a_j y_j$$ is an isometry of $H$ onto $H$, mapping $0$ to $0$. Furthermore every isometry of $H$ onto $H$ mapping $0$ to $0$ can be obtained in this fashion.

After struggling with the proof, I believe the last statement doesn't hold for complex Hilbert spaces. (Judging from the context, I think Lax would've stated it explicitly if the result only holds for real Hilbert spaces.) I've found a counterexample: $$f:\mathbb{C}^2\to\mathbb{C}^2$$ $$f(x,y) = (\operatorname{Re}x + i\operatorname{Im} y, \operatorname{Re}y + i\operatorname{Im} x)$$ Could someone tell me if I've made a mistake here, or is this an error in the book? Thanks!