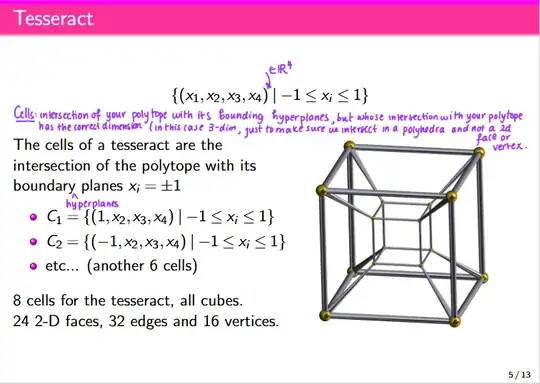

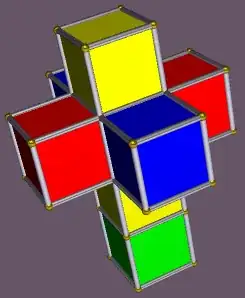

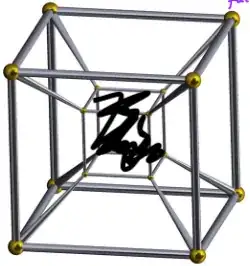

"Cells" here refers to "$3$-dimensional faces," so in the picture the cells are all solid cubes. The easiest one to see in the picture is the little cube in the middle; it's being left hollow but "cell" here is referring to the entire interior of that cube:

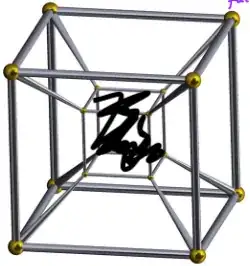

The little cube is also surrounded on each of its $6$ faces by $6$ other squashed cubes (which have a pyramidal shape in the picture, but in the "actual" hypercube these cubes are all the same size and shape). This accounts for $7$ cubes. Here I'm only going to indicate the one on the bottom so the image isn't too messy:

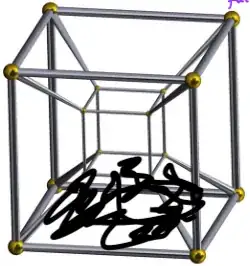

The $8$th cube is the hardest one to see; it is the entire region outside of the big cube, and in particular in this drawing of the hypercube it is infinite. This image is not even fully accurate because strictly speaking this final cube includes the "camera" from which we're viewing this whole thing but if I filled that in this whole image would be black:

This is, again, not how the "actual" hypercube works; here we're doing a stereographic projection to project the hypercube into 3d. Then that picture is a further projection into 2d! It's amazing that this gives us any meaningful information at all, really.

You can see that together the cubes fill up all of $\mathbb{R}^3$; this is really the $3$-sphere $S^3$ in $\mathbb{R}^4$, minus the point at infinity. This is the 4d analogue of the "spherical" drawing of a cube on a $2$-sphere $S^2$, which looks like this, and which also has a funny stereographic projection into $\mathbb{R}^2$ making one of the faces infinite, which I can't find a good picture of. But it's the 2d analogue of this diagram: a square inside another square, connected by $4$ edges.