Consider the measure space $(\mathbb{Q}, 2^{\mathbb{Q}}, \nu)$, with $\nu$ being the counting measure. The space is then $\sigma$-finite. Is there any attempts made to define analogues of continuous distributions on this space such that, when we sample from it (assuming we can), it shall look empirically like the corresponding continuous distribution? For example, can we define $N(0,1)$ on rationals? The problem is to find a density $f$ with respect to $\nu$ such that $\sum_{x \in \mathbb{Q}}f(x)$ makes sense. The traditional $\sum_{x \in \mathbb{Q}} e^{-\frac{x^2}{2}}$ does not seem to be working.

-

Counting measure is not a probability measure so how do you propose to sample from it? – Qiaochu Yuan Jul 18 '24 at 23:48

-

With some density it can become a probability measure. – 温泽海 Jul 19 '24 at 00:31

-

Plus, we do not discuss how to sample from a probability distribution in this context. We just assume that it can be done. – 温泽海 Jul 19 '24 at 00:34

-

I do not see how you plan to sum (as opposed to integrate) a density (as opposed to a probability mass function) and get $1$. You could create an discrete distribution on the rationals which is arbitrarily close to $N(0,1)$ in a CDF sense, but it would not be equal to it. – Henry Jul 19 '24 at 00:41

-

It is exactly the question how to do such a thing. How would you create discrete distribution on rationals such that, for instance, the uniform difference is smaller than $\epsilon$, where $\epsilon > 0$ is given? – 温泽海 Jul 19 '24 at 01:59

-

@温泽海 As an example, choose some positive integer $c>\frac1\epsilon$, consider all the positive rationals with denominator $\le c$, list them in the usual order (so for example $q_1=\frac1c, q_2=\frac1{c-1}, \ldots$ and there are a finite number in any interval), let $q_0=0$ and $q_{-i}=-q_i$. Then say $\mathbb P(X=q_i)=\Phi\left(\frac{q_{i+1}+q_i}{2}\right) - \Phi\left(\frac{q_{i}+q_{i-1}}{2}\right)$ and your CDF will be close to that of $N(0,1)$. The issue is that as $\epsilon$ decreases and $c$ increases, these probabilities will each tend towards $0$. – Henry Jul 19 '24 at 09:44

2 Answers

Expanded from comments:

I do not see how you plan to sum (as opposed to integrate) a density (as opposed to a probability mass function) and get 1. You could create an discrete distribution on the rationals which is arbitrarily close to $N(0,1)$ in a CDF sense, but it would not be equal to it.

As an example,

- choose some positive integer $c>\frac1\epsilon$,

- consider all the positive rationals with denominator $\le c$,

- list them in the usual order (so for example $q_1=\frac1c, q_2=\frac1{c-1}, \ldots$ and there are a finite number between any pair of integers),

- let $q_0=0$ and $q_{-i}=-q_i$.

- Then say $\mathbb P(X=q_i)=\Phi\left(\dfrac{q_{i+1}+q_i}{2}\right) - \Phi\left(\dfrac{q_{i}+q_{i-1}}{2}\right)$ and your CDF will be close to that of $N(0,1)$.

Here is an illustration when $c=6$ so the ordered rationals include $\cdots, -\frac12, -\frac25,-\frac13,-\frac14,-\frac15,-\frac16, \frac01, \frac16,\frac15,\frac14, \frac13, \frac25, \frac12, \frac35,\frac23,\frac34,\frac45,\frac56, \frac11, \frac76,\cdots$.

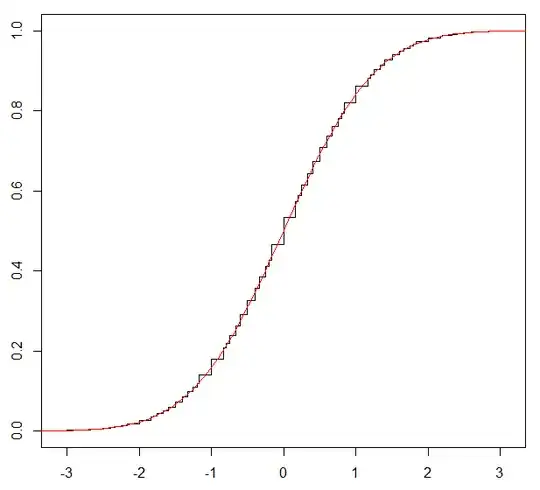

The CDF (in black, compared to the continuous $N(0,1)$ in red) looks like this and has a maximum error less than $0.03321$.

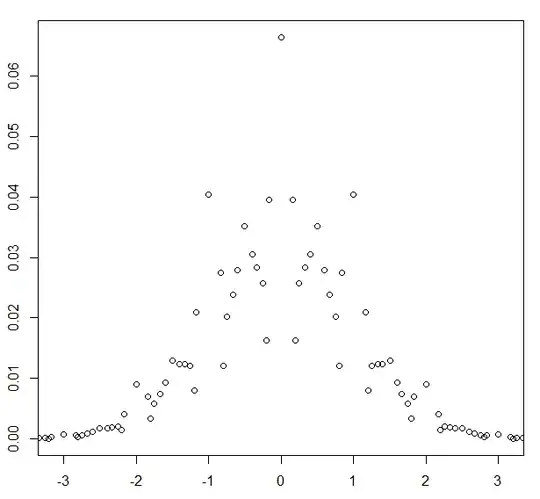

The corresponding probability mass function looks like

and you can sum these values as you wish, since there are a countable number of positive probabilities; overall the sum of probabilities will be $1$ as desired. It is not a density.

The issue is that as $\epsilon$ decreases and $c$ increases, these probabilities will each tend towards $0$, so there is not a useful limit.

- 169,616

I would say that "nice", "benchmark" continuous disributions tend to have regular supports - closure of the set on which its density (w.r.t. the Lebesgue measure) is positive. E.g. a uniform distribution is supported on an interval, exponential distribution is supported over a half-line and normal distribution has the whole real line as its support. In particular over the corresponding supports their densities are positive and continuous everywhere hence over each compact subinterval of their respective supports their densities attain the minimal value $\delta > 0$.

Recall however that if you take a countable number of values each above $\delta>0$, their sum will be infinite. On the other hand, any open interval of a real line contains a countable number of rationals. As a result, any probability distribution over rationals will have the property that $\inf_{a< r < b}p(r) = 0$ where the sum is taking over all rational numbers in an interval $(a, b)$ and $p$ is the probability mass function of your distribution.

So no matter where and how small you pick the open interval $(a, b)$, it will have a subsequence of rational numbers over which the probabilty mass function tends to zero. Unless you just let this function to be non-zero at a finite number of points within each such interval (see e.g. Henry's answer), you will get a function that looks rather unpleasant, definitely unlike anything that resembles uniform, exponential or normal densities.

- 36,568

-

+1. I like trying to construct distributions. For an attempt at a distribution with positive probability on each of the rationals in $(0,1)$, see https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/189813/is-this-graph-based-on-rationals-familiar - but that is still a discrete distribution. – Henry Jul 19 '24 at 11:24

-

while thinking about why can't we have a pmf for a cdf of normal distribution projected on rationals, I've realized I don't know an example of a function that goes from 0 to 1 monotonically but is not CDF. I guess it must be a non-cadlag function. Do you know of any example @Henry – SBF Jul 19 '24 at 11:26

-

You are correct, at least for a distribution with support on $\mathbb R$ or on a subset of $\mathbb R$. Any weakly increasing càdlàg function $F:\mathbb R \to \mathbb R$ with $\lim\limits_{x\to -\infty}F(x)=0$ and $\lim\limits_{x\to +\infty}F(x)=1$ can be seen as a CDF of a distribution, while no other function $\mathbb R \to \mathbb R$ can. – Henry Jul 19 '24 at 11:36

-

@Henry I've meant do you know of example of a non-cadlag function satisfying all other conditions and failing to be a CDF? Edit: nvm. One just shows that CDF must be cadlag due to properties of a probability measure, hence a non-cadlag candidate function fails to be a CDF. – SBF Jul 19 '24 at 11:42

-

1So $F(x)=0$ for $x\le 0$, $F(x)=1$ for $x >0$ is not càdlàg at $0$ and not the CDF of a distribution - otherwise we would have to say that the probability $X$ is $0$ or negative is $0$ and the probability $X$ is strictly positive is also $0$ even though $0+0 \not = 1$. Slightly adjusting this to $F(x)=0$ for $x\lt 0$, $F(x)=1$ for $x \ge 0$ would be càdlàg and would tell us $\mathbb P(X=0)=1$. – Henry Jul 19 '24 at 11:56