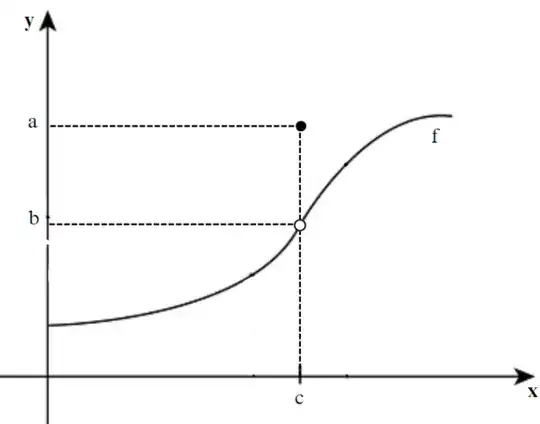

My math book states that for a limit to exist at a point

$a$ of a function $f$, $f(a)$,

must be equal to the limiting values from each side of the point. However, how does the epsilon-delta definition exclude the cases where

$f(a)$

is different from the values from each side of the point? How does this definition prove there is no limit in cases like this one in the image?

Asked

Active

Viewed 81 times

0

Sebastiano

- 8,290

-

1Have you fully understood the epsilon-delta definition of a limit? Once you do, experiment a bit and the answer should be trivial – Zima Jun 23 '24 at 15:00

-

2The comment above is wrong. The limit $\lim_{x\to c} f(x)$ exists, and it's $b$. The $\epsilon-\delta$ definition works because it explicitly allows you to calculate the limit as $b$. There's nothing wrong with $f(c)=a$ and $\lim_{x\to c} f(x) = b$, they can be different. When they're the same, then the function is continuous at that point. – Amaan M Jun 23 '24 at 15:32

-

1From what I have read on this site, there are two ways continuity is defined in beginning calculus textbooks. In the way I am familiar with, the limit in the figure exists but is not equal to $f(c)$, therefore $f$ is not continuous at $c$. But according to the other definition, the limit does not even exist. I think we need to see exactly what your book has said, including the full and complete definition of the limit of $f(x)$ as $x$ approaches a given point. – David K Jun 23 '24 at 15:49

-

@David K: But according to the other definition, the limit does not even exist. --- Could you give a specific reference for "the other definition"? I strongly suspect you misread something here or the poster misstated (or did not understand) something. – Dave L. Renfro Jun 23 '24 at 17:13

-

2@DaveL.Renfro I don't remember where I saw this. It had something to do with undergraduate education in France as far as I recall. Basically, the difference is that when taking a limit at a finite point $c$, the neighborhood of that point is not punctured, so the value of $f(c)$ itself will prevent taking a limit if $f$ is not continuous at $c$. Possibly it was https://math.stackexchange.com/q/1794652/139123. – David K Jun 23 '24 at 18:00

-

@David K: This is interesting because it differs from standard practice in the (research) literature that I'm familiar with. I have, however, encountered non-deleted notions for lim-inf and lim-sup -- see my comments to this MSE question and the later portion of this mathoverflow answer (see "Olsen's punctured upper limit and $\ldots$"). – Dave L. Renfro Jun 23 '24 at 22:22

-

@DaveL.Renfro: https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/2768350/french-limits-are-different, https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/3298744/mistake-in-french-wikipedia-on-definition-of-limit, https://math.stackexchange.com/questions/4640788/what-is-the-right-definition-for-the-limits-from-the-left-and-the-right – Hans Lundmark Jun 24 '24 at 05:42

-

@Hans Lundmark: I've known (for several decades) about the Bourbaki use of "positive" to mean what many others call "non-negative" (i.e. $x$ is a positive real number if $x \geq 0)$ and "strictly positive" for what many others call "positive". Indeed, I've known several people who had the Bourbaki versions in their school mathematics courses. However, this issue with limits is new to me; at least, I don't recall coming across it before. – Dave L. Renfro Jun 24 '24 at 08:17

-

@DaveL.Renfro: nLab also makes a very clear distinction between “French” and “English” limits: https://ncatlab.org/nlab/show/limit+of+a+function. – Hans Lundmark Jun 24 '24 at 08:31