Natural language is a tempting example for information theory - after all, it is the most familiar form of code for almost everyone. But for a first introduction to the concept, it's deceptively complicated. Natural language statements contain much more information than meets the eye.

Teaching Shannon entropy to high school students is particularly hard because they're unlikely to yet have the mathematical fundamentals to really understand why entropy "works." It's fairly easy to describe entropy loosely as the amount of "uncertainty" or "redundancy" in a random variable or signal. However, there are many such measures we could use - why is this funky sum-of-logarithms the "correct" one?

I have a fairly specific opinion on this, which I'll borrow from an earlier post of mine on cross-validated:

Given some (discrete) random variable X, we may ask ourselves what the "average probability" of the outcomes of X are. To do this properly, we need to take a geometric mean. Unfortunately, geometric means are obnoxious - conveniently for us, though, the logarithm of the geometric mean is the arithmetic mean of the logarithm.

Viewed this way, information theory really is "just" probability theory, except we've taken logarithms to turn multiplication into addition.

There are a number of other ways to "single out" Shannon's formula as the "natural" measure of information (see: convexity), but to me this one is the most-intuitively-accessible. Even so, most high school students are unlikely to be familiar with the geometric mean, much less have any intuition for it, and so this can be really hard to get across.

Since students are already likely to struggle understanding the motivation for the entropy formula, it's doubly hard for them to deal with ambiguities in interpreting its output. The above intuition is pretty hard to teach a high school student even when describing the simple case of a weighted coin-flip (or die toss), where there is only one possible way to assign probabilities and it is plainly obvious what the "information" we've calculated actually corresponds to in terms of the values of the signal.

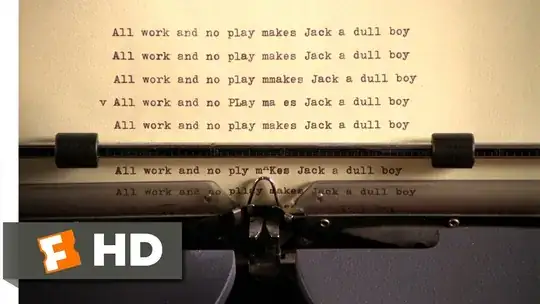

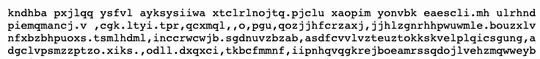

But natural language is (clearly) not just a simple coin-flip or die-toss. If we naively count character frequencies over a representative corpus, the information content we calculate using Shannon's formula is from the point of view of a generating process that looks more like The Library of Babel than natural language:

The idea that information is contextualized in this way - that it is "from the point of view" of some generating process - is itself crucial to understanding and using entropy in practice. But if you start off with one of the most-complicated cases imaginable when first introducing the concept, this can easily be misunderstood or overlooked entirely.

I suggest a phased approach: start with a weighted coin toss or some other trivial base case when first introducing the concept. Once the basic idea has been established, you can work through calculating entropies for strings of text with increasing amounts of detail/memory (i.e., as a Markov process of increasing order) so you can illustrate how we use this (finitary) theory to approximately describe signals that may carry infinite information. Without this foundation, it's very hard to understand what the entropy value means.

How much "hard" mathematics you do at each step depends on your students and the amount of time you have, but I strongly suggest painting the full picture - simple to complex - and really taking time to talk about the interpretational issues. Interpretation here is more important than the math.