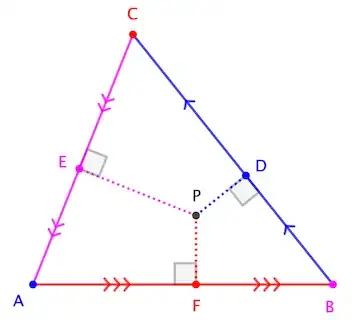

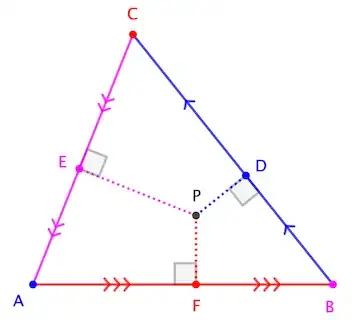

Consider $\triangle ABC$ with perpendiculars at points $D$, $E$, $F$ on the side-lines meeting at point $P$, as shown:

The positions of $D$, $E$, $F$ are not independent; choosing any two constrains the third. The Ceva-like relation governing these positions is known as Carnot's Theorem:

$$|DC|^2+|EA|^2+|FB|^2 \;=\; |BD|^2+|CE|^2+|AF|^2 \tag1$$

Equivalently, since $a=|DC|+|BD|$, etc, we find

$$a\,|DC| + b\,|EA| + c\,|FB| \;=\; a\,|BD| + b\,|CE| + c\,|AF| \tag2$$

(A decade(!) ago, I (re-)proved this theorem in this Math.SE answer. I dubbed the result "Ortha's Theorem" as a back-construction of "orthian", a term I coined for the perpendiculars at $D$, $E$, $F$, mimicking the name "cevian" and its derivation from Ceva's Theorem.)

With a little bit of effort, and some manipulation based on $(1)$ or $(2)$, one can derive the following barycentric representation of the point $P$:

$$P = \frac{u A + v B + w C}{u+v+w}$$

where

$$\begin{align}

u &\;:=\; a\;\left(\;

-a\,|BD||DC|

\;+\;b\,|BD||CE|

\;+\;c\,|FB||DC| \;\right) \tag3 \\[4pt]

v &\;:=\; b\;\left(\;

-b\,|CE||EA|

\;+\;c\,|CE||AF|

\;+\;a\,|DC||EA| \;\right) \tag4 \\[4pt]

w &\;:=\; c\;\left(\;

-c\,|AF||FB|

\;+\;a\,|AF||BD|

\;+\;b\,|EA||FB| \;\right) \tag5 \\[4pt]

u+v+w &\;=\; 4\,|\triangle ABC|^2 \tag6

\end{align}$$

In the above, $|\triangle ABC|$ represents the area of the triangle. Also, distances are considered "signed" relative to the oriented sides $\overrightarrow{AB}$, $\overrightarrow{BC}$, $\overrightarrow{CA}$ of the triangle. For instance, $|AF|$ is positive when $\overrightarrow{AF}$ and $\overrightarrow{AB}$ point in the same direction; and negative when in the opposite direction.

When $D$, $E$, $F$ are midpoints, so that

$$|BD|=|DC|=\tfrac12a \qquad |CE|=|EA|=\tfrac12b \qquad |AF|=|FB|=\tfrac12c$$ then $$u:v:w \;=\; a \cos A : b \cos B : c \cos C \tag7$$ These are the barycentric coordinates of the circumcenter.

When $D$, $E$, $F$ are the feet of altitudes, so that

$$|BD|=c\cos B \qquad |DC|=b\cos C \qquad \text{etc}$$ then $$u:v:w \;=\; \frac{a}{\cos A}:\frac{b}{\cos B}:\frac{c}{\cos C} \tag8$$ These are the barycentric coordinates of the orthocenter.

When $D$, $E$, $F$ are the "touch points" of the incircle, so that

$$\begin{align}

|EA|=|AF|&=\tfrac12(-a + b + c) \\

|BD|=|FB|&=\tfrac12(-b + c + a) \\

|DC|=|CE|&=\tfrac12(-c + a + b)

\end{align}$$ then

$$u:v:w \;=\; a:b:c \tag9$$ These are the barycentric coordinates of the incenter.

Addendum. Here' s an alternative representation of the above in terms of ratios $\alpha$, $\beta$, $\gamma$ such that

$$

\overrightarrow{BD}\;=\;\alpha\,\overrightarrow{BC}\qquad

\overrightarrow{CE}\;=\;\beta\,\overrightarrow{CA}\qquad

\overrightarrow{AF}\;=\;\gamma\,\overrightarrow{AB}

$$

That is, a ratio expresses how far along an edge one of these points is, with travel along the edges take to be in the directions $B\to C$, $C\to A$, $A\to B$. (OP mentions taking these ratios in the interval $[0,1]$, but there's no geometric or algebraic reason they can't be arbitrary real numbers: greater than one for traveling beyond the far endpoint of an edge, and less than zero for traveling the "opposite" direction.)

Then, making the substitutions

$$

|BD|\to a\,\alpha \qquad |DC|\to a\,(1-\alpha) \\

|CE|\to b\,\beta \qquad |EA|\to b\,(1-\beta) \\

|AF|\to c\,\gamma \qquad |FB|\to c\,(1-\gamma)$$

into Carnot's relation gives

$$a^2 + b^2 + c^2 \;=\; 2 \left(\; a^2\,\alpha \;+\; b^2\,\beta \;+\; c^2\,\gamma\;\right) \tag{1'}$$

which makes solving for one ratio in terms of the other two straightforward. (Sanity check: The relation holds for $\alpha=\beta=\gamma=\tfrac12$, as it should for the case where $P$ is the circumcenter.)

Further, defining $\alpha' :=1-\alpha$, etc, to reduce clutter, we find that $(3,4,5,6)$ become

$$\begin{align}

u &\;=\; a^2 \left(\;-a^2\,\alpha\alpha' \;+\; b^2\,\alpha\beta \;+\; c^2\,\alpha'\gamma'\;\right) \tag{3'}\\[4pt]

v &\;=\; b^2 \left(\;-b^2\,\beta\beta' \;+\; c^2\,\beta\gamma \;+\; a^2\,\beta'\alpha'\;\right) \tag{4'}\\[4pt]

w &\;=\; c^2 \left(\;-c^2\,\gamma\gamma' \;+\; a^2\,\gamma\alpha \;+\; b^2\,\gamma'\beta'\;\right) \tag{5'}\\[4pt]

u+v+w &\;=\; 4\,|\triangle ABC|^2 \tag{6'}

\end{align}$$

and we still have

$$P \;=\; \frac{u}{u+v+w}\,A \;+\; \frac{v}{u+v+w}\,B \;+\; \frac{w}{u+v+w}\,C$$

where we can interpret the points as their coordinate vectors.