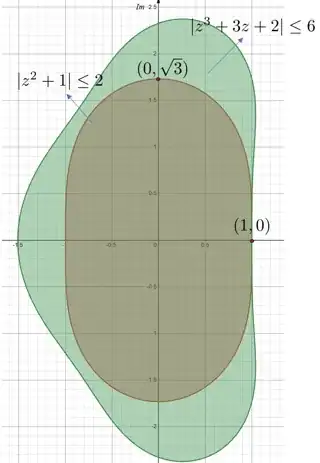

Show that $$\{z \in \mathbb{C}: |z^2+1|\le 2 \} \subseteq \{z \in \mathbb{C} : |z^3+3z+2|\le 6 \} \tag{*}$$ (In other words: Let $z\in \mathbb{C}$ satisfy $|z^2+1|\le 2$. Prove that $|z^3+3z+2|\le 6.$)

This problem was asked by mengdie1982 roughly a day ago(relative to posting this question), but was closed due to lack of work. This has been bothering me because of how simply it has been stated, however even after hours of work I am not close to proving this mathematically. Geometrically the statement (*) is true, as seen below.

Here are some estimates:

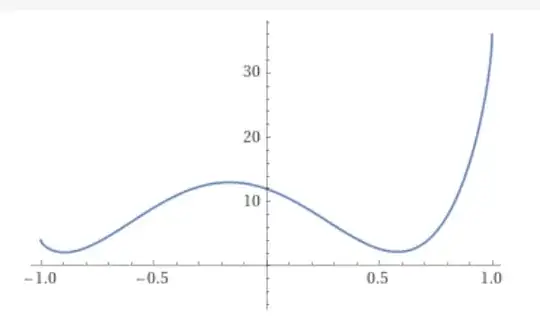

- From reverse triangle inequality, $|z^2+1| \le 2$ implies $|z| \le \sqrt{3}$ with equality at $z=i\sqrt{3}$. From triangle inequality, $|z^3+3z+2| \le |z|^3+3|z|+2 \le 6\sqrt{3}+2 \approx 12.4$. A better bound can also be achieved by factorization, $$|z^3+3z+2| = |z(z^2+1)+2(z+1)| \le |z||z^2+1|+2(|z|+1) \le 4\sqrt{3}+2 \approx 8.93. $$

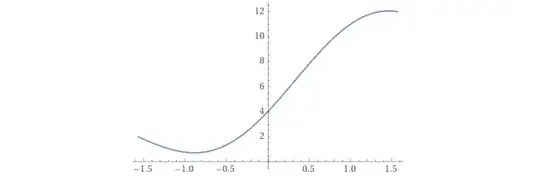

- Another approach I took was to show that for any $r<6$, $$\{z \in \mathbb{C}: |z^2+1|\le 2 \} \nsubseteq \{z \in \mathbb{C} : |z^3+3z+2|\le r \} $$ which explains the pinching behavior between the sets near the point $(1,0)$. Define $$L=\left(\frac{2}{2-r+\sqrt{8-4r+r^{2}}}\right)^{\left(\frac{1}{3}\right)},\quad z_0 = \frac{1}{2}\left(1+L-\frac{1}{L}\right), $$ then with much effort, it can be shown that $z_0$ satisfies $|z^2+1|\le 2$, but it is not present in the other set. This implies that (*) can be reworded as finding the largest $r>0$ such that $$\{z \in \mathbb{C}: |z^2+1|\le r \} \subseteq \{z \in \mathbb{C} : |z^3+3z+2|\le 6 \}$$

or it is possible that there is an easier solution which I am missing.