A more natural way to define them is analogous to Riemann sums. Indeed for the usual Riemann integral we would define

$$\int_a^bf(x)\,\mathrm{d}x:=\lim_{\lVert\mathcal{P}\rVert\to0}\sum_{j=1}^nf(x_j^*)(x_j-x_{j-1}),$$

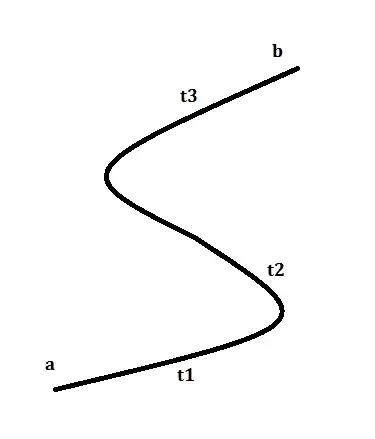

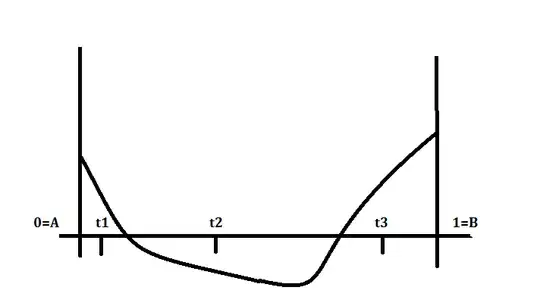

where the limit is taken over all tagged partitions $\mathcal{P}$ of $[a,b]$. Say we instead want to integrate along a curve $\gamma$. Then a very natural way to do this would be to replace the $x_j-x_{j-1}$ with $\gamma(x_j)-\gamma(x_{j-1})$, i.e. the distance between two points on the curve, and to replace $x_j^*$ with $\gamma(x_j^*)$, as we wish to evaluate our function at a point on the curve between the two we just measured the distance of. This leads us to defining

$$\int_\gamma f(z)\,\mathrm{d}z:=\lim_{\lVert\mathcal{P}\rVert\to0}\sum_{j=1}^nf(\gamma(x_j^*))(\gamma(x_j)-\gamma(x_{j-1})),$$

where $\gamma:[a,b]\to\mathbb{C}$ is a curve. Let us assume that $\gamma$ is $C^1$. Then we have the expansion

$$\gamma(t)=\gamma(s)+\gamma'(s)(t-s)+R(t-s),$$

where $\frac{R(t-s)}{t-s}\to0$ as $t\to s$. Consequently

$$\gamma(x_j)-\gamma(x_{j-1})=\gamma'(x_{j-1})(x_j-x_{j-1})+R(x_j-x_{j-1}).$$

But then notice that

\begin{align*}

\sum_{j=1}^nf(\gamma(x_j^*))(\gamma(x_j)-\gamma(x_{j-1}))

&=\sum_{j=1}^nf(\gamma(x_j^*))(\gamma'(x_{j-1})(x_j-x_{j-1})+R(x_j-x_{j-1})) \\

&=\sum_{j=1}^nf(\gamma(x_j^*))\gamma'(x_{j-1})(x_j-x_{j-1})+\sum_{j=1}^nf(\gamma(x_j^*))R(x_j-x_{j-1}).

\end{align*}

Notice how the first term in this sum looks an awful lot like a Riemann sum for the integral $\int_a^bf(\gamma(t))\gamma'(t)\,\mathrm{d}t$, the only difference being that we evaluate $f\circ\gamma$ and $\gamma'$ at different points in the subintervals of the partition. This is where the assumption of $\gamma$ being $C^1$ saves us. I will not go into the details, because my point is to give you the idea of why the definition you've seen makes sense, but one can now show that the second term also vanishes as the mesh of the partition goes to zero, and so one obtains that

$$\int_\gamma f(z)\,\mathrm{d}z=\lim_{\lVert\mathcal{P}\rVert\to0}\sum_{j=1}^nf(\gamma(x_j^*))(\gamma(x_j)-\gamma(x_{j-1}))=\underbrace{\lim_{\lVert\mathcal{P}\rVert\to0}\sum_{j=1}^nf(\gamma(x_j^*))\gamma'(x_{j-1})(x_j-x_{j-1})}_{=\int_a^bf(\gamma(t))\gamma'(t)\,\mathrm{d}t}+\underbrace{\lim_{\lVert\mathcal{P}\rVert\to0}\sum_{j=1}^nf(\gamma(x_j^*))R(x_j-x_{j-1})}_{=0}=\int_a^bf(\gamma(t))\gamma'(t)\,\mathrm{d}t,$$

and so you can see that, with this much more natural definition, analogous to what we do on the real line, we obtain the formula you have for sufficiently nice functions.