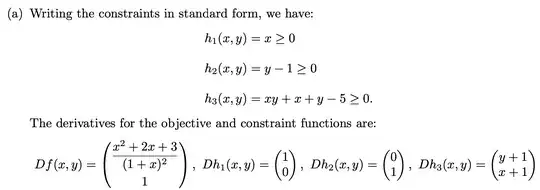

When checking whether the CQ are satisfied in KKT, i.e. checking for Linear Independence amongst all combinations of the constraints.

Is it true to say we only need to check combinations that could be simultaneously effective (binding)? So if two constraints can't bind at the same time i.e. they would create the empty set, i don't need to check their gradient vectors for Liner Dependence?

This seems to be the case but i recently came across the following in a mark scheme, i'm struggling to interpret it, and wondered if it was stating the above but only for mixed constraint problems.

For mixed constraint problems, we follow the same approach as for inequality constraint optimisation problems, but we can restrict our attention to just those combinations of effective constraints that include the equality constraints.

I would also appreciate some intuition as to why the importance of Linear Dependence in the context of KKT constraints is I feel like the Lagrange/KKT solutions wouldn't know how to allocate tangent points if multiple constraints were LD - somewhat analogous to how regression fails with perfect collinearity of regressors? Thanks!

Example

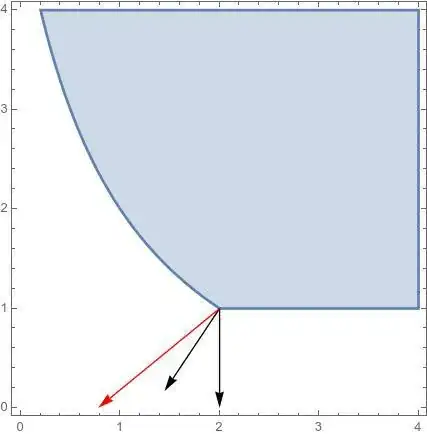

Taking the example in the image below:

• I would state that the CQ holds for $h_1, h_3$ because if $h_1$ is binding $x = 0$ which implies $y=5$, which creates vectors $(0,1)$ and $(6,1)$ which are LI.

• Their approach is always the other way round. They say for $h_1$ and $h_3$ to be LD, then $x = -1$ this violates the constraint $h_1$

Are both approaches valid? Does my approach of starting with the implications of the constraints being binding run into any problems, compared with starting with the implications of the constraints being LI.