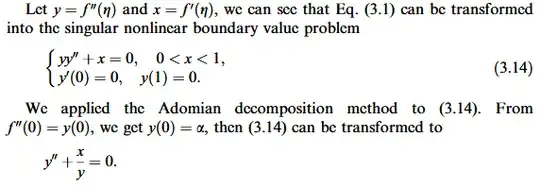

I'm not sure, but my guess is that in Eq. (3.14), $y$ is interpreted as a function of $x$, so that $y'$ is the derivative of $y$ with respect to $x$ (and not $\eta$): $y'(x) = \partial_x y(x)$. With that said, one has $\partial_\eta y (x) = (\partial_\eta x) (\partial_x y)$ by the chain rule, and the expressions $x = f'(\eta)$, $y = f''(\eta)$ imply that

$$ y'(x) = \partial_x y = \frac{\partial_\eta y (x)}{\partial_\eta x} = \frac{f'''(\eta)}{f''(\eta)} = -f(\eta)\ \ \ \text{from Eq. (3.1).}$$

Taking $\eta = 0$ then gives $y'(f'(0)) = y'(0)$ for the left-hand side, and $f(\eta) = 0$ for the right-hand side (using the boundary conditions (3.2)). Hence, $y'(0) = 0$.

As for $y(1) = 0$, I don't know the answer, but it has to do with the fact that $$y(1) = \lim_{x \to 1} y(x) = \lim_{\eta \to +\infty} y(x = f'(\eta)) = \lim_{\eta \to +\infty} f''(\eta).$$

Now if a function (here $f'$) has a limit at infinity ($1$ according to Eq. (3.2)), it doesn't necessarily imply that its derivative ($f''$) tends to $0$ (See e.g. this counterexample). However, according to this answer, $f' \to 1$ will imply $f'' \to 0$ if $f''$ is uniformly continuous on $[0, +\infty)$.