Consider an undirected complete graph $G_n$ with $n$ vertices, where if the numerical labels of each vertex are consecutive, then the edge between them is $1$, and the edge between the numerical labels on first and last vertices is also $1$. The edge between any other pair of vertices is $n$.

Based on this property, consider a Hamiltonian circuit vertex arrangement $(a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n)$, which is composed of edges of $n$ and $1$, so its is $k \cdot n + (n - k)$, where $k$ represents the number of edges of $n$ in the arrangement.

For example, the arrangement $(1,2,3,4)$ corresponds to $k=0$, and the arrangement $(1,3,2,4)$ corresponds to $k=2$, because the edges $(1,3)$ and $(2,4)$ are not numerical consecutive, so there are $2$ edges of $n$.

The question is:

(1) Given the number $k$ of edges of $n$, how many Hamiltonian circuits have a of $k \cdot n + (n - k)$? In other words, the question can be transformed into:

How many Hamiltonian circuits contain $k$ edges of $n$?

What is known so far by my intuition($n\geq 7$):

- When $k=0$, there is $1$ circuit.

- When $k=1$, there is no circuit.

- When $k=2$, there are $\frac{n(n-3)}{2}$ circuits.

- When $k=n-2$, the number of circuits does not exceed $\frac{20}{6!} \cdot n \cdot (n-2)!$.

However, for other cases, there is currently no method of estimation.

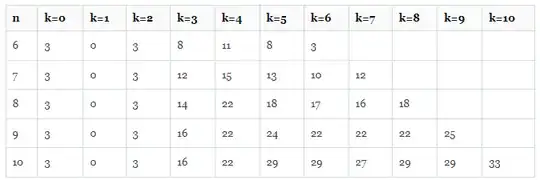

Here is my numerical experiment on $n=5$ to $n=11$

(2) For a given permutation of $V(G_n)$ given by: $$H=(\pi_1,\pi_2,...,\pi_{i-1},\pi_{i},\pi_{i+1},...,\pi_{j-1},\pi_{j},\pi_{j+1},...,\pi_n),$$ a 2-opt swap operation, $\eta_{i,j}(H)$, transforms $H$ into another permutation, specifically: $$H'=\eta_{i,j}(H)=(\pi_1,\pi_2,...,\pi_{i-1},\pi_{j},\pi_{j-1},...,\pi_{i+1},\pi_{i},\pi_{j+1},...,\pi_n),$$ In $H'$, the vertices from the $1$st to the $i-1$th in $H$ are copied with the same order to $H'$, while the vertices from the $i$th to the $j$th in $H$ are reversed and copied into $H'$. Finally, the vertices from the $j+1$th to the $n$th in $H$ are maintained in the same order and copied to $H'$.

In the complete graph $G_n$, we divide the set $\mathcal{H}$ of all Hamiltonian cycles into layers based on the number of edges of length $n$ they contain: $$L_i = \{H \in \mathcal{H} : w(H) = in + n - i, i = 0, \dots, n\}.$$ Then we define: $$\sigma_{k \to k+l}(H) = \#\{i \in \{1, \dots, n\}, j \in \{i+1, \dots, n\} : \eta_{i,j}(H) \in L_{k+l}, H \in L_{k}\},$$ which means the total number of possible operations for edges that can transition a Hamiltonian cycle $H$ in layer $L_k$ to layer $L_{k+l}$ through a 2-opt operation.

For example, if $H = (3,6,1,2,4,5)$, then: $$\sigma_{3 \to 3}(H) = \#\{(1,2),(1,3),(1,5),(1,6),(2,6),(3,6),(4,6)\} = 7,$$ because:

$\eta_{1,2}(H) = (6, 3, 1, 2, 4, 5) \in L_3$

$\eta_{1,3}(H) = (1, 6, 3, 2, 4, 5) \in L_3$

$\eta_{1,5}(H) = (4, 2, 1, 6, 3, 5) \in L_3$

$\eta_{1,6}(H) = (5, 4, 2, 1, 6, 3) \in L_3$

$\eta_{2,6}(H) = (3, 5, 4, 2, 1, 6) \in L_3$

$\eta_{3,6}(H) = (3, 6, 5, 4, 2, 1) \in L_3$

$\eta_{4,6}(H) = (3, 6, 1, 5, 4, 2) \in L_3$

We define $\xi_{k \to k+l} = \{\sigma_{k \to k+l}(H) : H \in L_k\}$ as the set of all possible numbers of operations for elements in layer $L_k$ to transition to layer $L_{k+l}$.

Question is, given $n, k, l$, determine the bounds for $|\xi_{k \to k+l}|$.

For this question, there is currently no clear solution strategy.

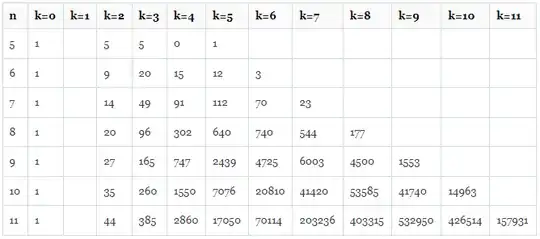

Here is my numerical experiment on $n=5$ to $n=11$ and $l=0$

the meaning of number in the cell=$\max\{\sigma_{k\to k+l}(H):H\in L_k\}$