The answer in the post you linked has it exactly backwards. $x$ vanishes to order $2$ at $(0,0)$, and $y$ vanishes to order $1$. But the method in the linked post is correct; they just made a computational mistake.

Let’s take as given that $y$ is a uniformizer at $P = (0,0)$; to remind us of this, write $t = y$. My answer here shows this, but we’ll also see that this must be the case from our calculations. To determine $\newcommand{\ord}{\operatorname{ord}} \ord_P(x)$, we want to express $x$ as a power series in $t$. From the equation for the curve, we have $t^2 = x^3 + x$. Letting $g(t)$ be the compositional inverse (also called the reversion) of $x^3 + x$, then

$$

g(t) = t - t^3 + 3 t^5 - 12 t^7 + 55 t^9 - 273 t^{11} + \cdots

$$

and $g(x^3 + x) = x$. Applying $g$ to both sides of $t^2 = x^3 + x$ yields $g(t^2) = x$, so the correct parametrization is

$$

t \mapsto (x,y) = (g(t^2), t) \, .

$$

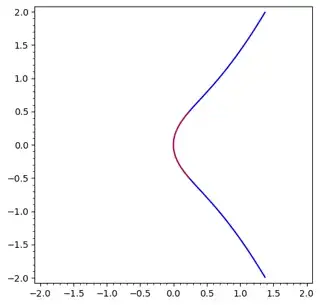

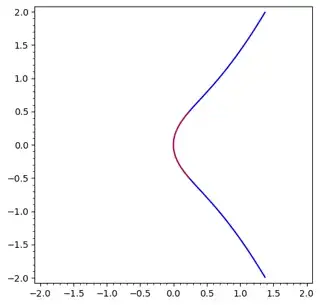

From this we see that $y=t$ is a uniformizer and $x = g(t^2) = t^2 - t^6 + 3 t^{10} - 12 t^{14} + \cdots$, so $x$ vanishes to order $2$ at $P$, as I claimed. Here is a plot, made in this SageMath cell, showing in red the portion of the curve parametrized for $t \in [-1/2, 1/2]$.

$\hspace{3.5cm}$

But what if we instead mistakenly thought that $t=x$ was a uniformizer at $(0,0)$ and tried to express $y$ as a function of $t$? From the equation of the curve, we have $y^2 = t^3 + t$, so we’d like to write $y = \sqrt{t^3 + t}$ as a power series. But $t + t^3$ doesn’t have a square root in $k[[t]]$: for contradiction, suppose that $h(t) = \sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i t^i$ were such a square root, so $h(t)^2 = t + t^3$. Then

\begin{align*}

t + t^3 = \left(\sum_{i=0}^\infty a_i t^i\right)^2 = a_0^2 + 2 a_0 a_1 t + (2 a_0 a_2 + a_1^2) t^2 + (2 a_0 a_3 + 2 a_1 a_2) t^3 + \cdots \, .

\end{align*}

Matching coefficients of $t^i$, we have $a_0 = 0$, so $2 a_0 a_1 = 0$, and hence the righthand side has no $t$ term, contradiction. (In order for $\sqrt{t + t^3}$ to exist, we’d have to pass to the ring $k[[t^{1/2}]]$ of Puiseux series. The fact that this requires exponents with denominator $2$ also suggests that $x$ vanishes to order $2$.)

As for your question, “why the order (defined with ideals) corresponds to the terms in the Taylor series?”: for simplicity, let's assume that $k$ is algebraically closed. Given a smooth point $P$, consider the local ring $k[C]_P$ at $P$ with unique maximal ideal $\newcommand{\m}{\mathfrak{m}} \m$; let $t$ be a uniformizer, so $\m=(t)$. We can complete this ring with respect to $\m$ to obtain the complete local ring $\widehat{k[C]_P}$

. It's a theorem that $\widehat{k[C]_P} \cong k[[t]]$, the power series ring in $t$ (see here). We have a ring morphism $k[C]_P \to \widehat{k[C]_P}

\cong k[[t]]$, which basically amounts to writing a function $f$ regular at $P$ as a power series in the uniformizer $t$. Note that, for both $k[C]_P$ and $k[[t]]$, all of their ideals are of the form $(t^v)$ for some $v \in \mathbb{Z}_{\geq 0}$, and the map $k[C]_P \to k[[t]]$ takes $t^v$ to $t^v$, so it preserves valuations. And given a series $a_v t^v + a_{v+1} t^{v+1} + \cdots$ with $a_v \neq 0$, since

$$

a_v t^v + a_{v+1} t^{v+1} \cdots = t^v\left(a_v + a_{v+1} t + \cdots\right) \, ,$$

and $a_v + a_{v+1} t + \cdots$ doesn’t vanish at $t=0$, then its order of vanishing is $$. For an example, see this answer of mine.