I am looking for references containing results on the minimum $k$ for which every positive integer of the interval $(kn,(k+1)n)$ is composite.

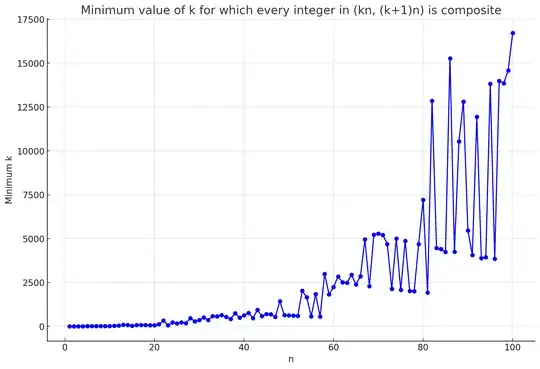

If we denote as $k(n)$ this minimum $k$ for some $n$, $k$ is indeed always equal or greater than $n+2$, and grows exponentially as $n$ grows. I attach the graph of $k(n)$ for $n\leq 100$.

The exponential growth could be reasonable, and suggests that some exponential lower bound for $k(n)$ could indeed be established for all $n>N_0$.

What I do not find "so reasonable" is the great variations that appear between $k(n)$ and $k(n+1)$.

So,

My questions:

Is there any result concerning lower bounds of $k(n)$? I will appreciate the references of any paper addressing $k(n)$.

Why do we have this great variation between $k(n)$ and $k(n+1)$ for so many $n$?

Thanks for your time!

EDIT

After reviewing the partial answer provided by @Eric, it surprises me that, looking at the exponential growth showed in the graph, it has not even been established a lower bound of $k(n)$ equal or greater than $n+2$. Why is such a result so difficult?

After having a closer look at the minimum intervals at each $k(n)$, it seems that a necessary condition for having that every positive integer of the interval $(kn,(k+1)n)$ is composite is that at least one of those composites is not divisible by prime numbers less or equal than $n$. Is that so? I can provide examples for $k(n\leq 3)$:

$k(2)=4$

We need the first composite number of the form $2x+1$. It is straightforward that this number is $3^2=9$, and thus $k(2)=4$.

$k(3)=8$

We need the first consecutive composite numbers of the form $3x+1$ and $3x+2$. It is clear that $2$ divides one of them, and $3$ does not divide any of them; therefore, it is straightforward that the minimum odd number of the wanted pair is $5^2=25$, and thus $k(3)=8$.

Despite these easy cases, a general proof seems difficult. It would need to be shown (through a process similar, or different, that the one I have showed for $n\leq 3$) that for consecutive integers $nx+1, nx+2,..., nx+(n-1)$ it is impossible that all of them are divisible by prime numbers less than $n$ if $x\leq n+2$.