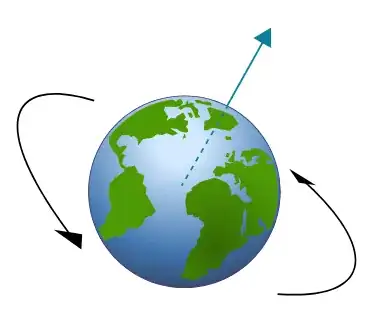

If a solid ball (like the Earth) is rotating in 3D space, you can point a single 3D vector out of the North Pole (according to the right hand rule), with the length of that vector proportional to the speed of rotation, and that single vector unambiguously and completely describes how the object is rotating.

My question is: does this extend to 4 dimensions and higher? Or is more than 1 vector needed to completely pin down how a solid object rotates in 4D? If so, how does the number of vectors needed increase with dimension?