Whichever form is more useful to you depends on what exactly you need (just points inside the triangle or equally densely distributed points). Also take a look at https://blogs.sas.com/content/iml/2020/10/19/random-points-in-triangle.html, which uses another approach that is also plausible.

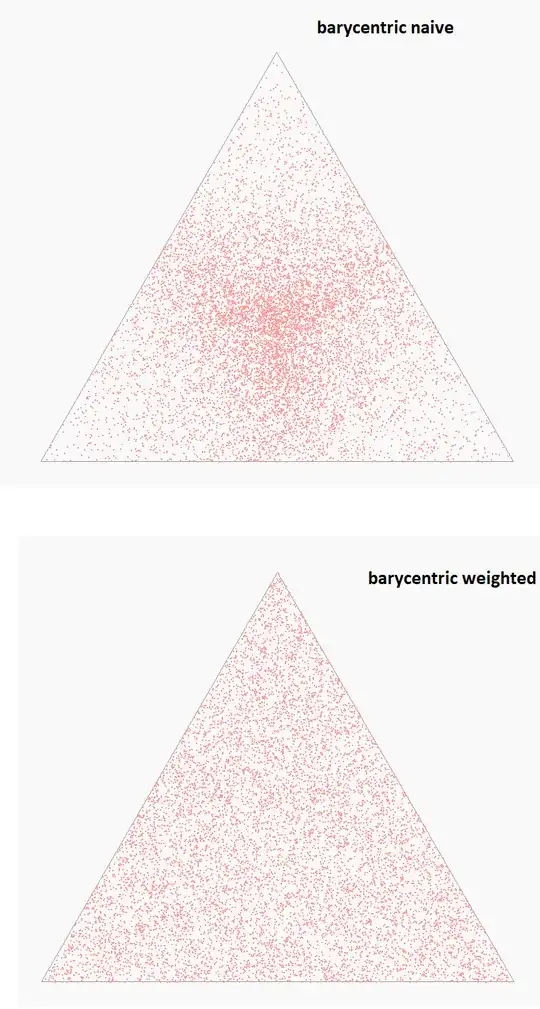

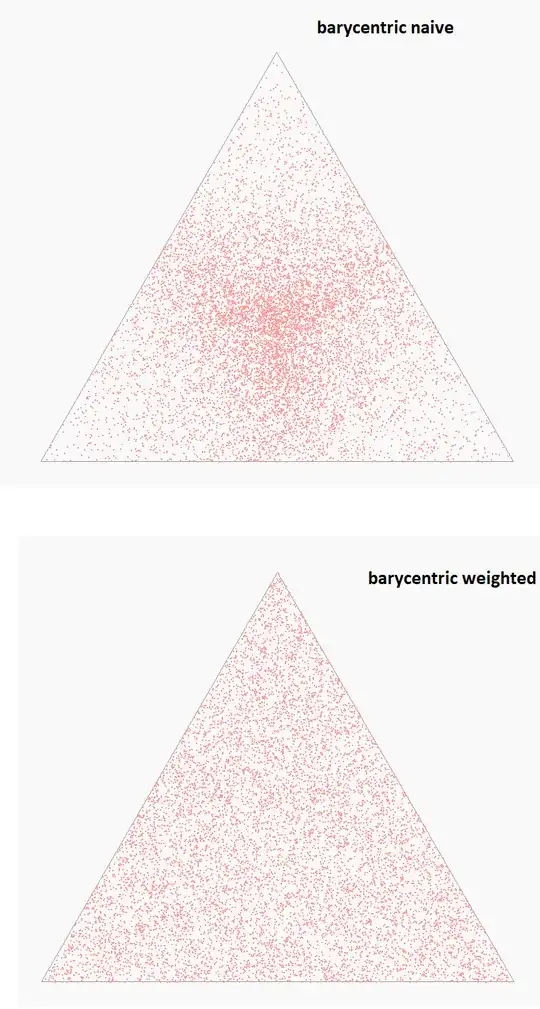

Compare the following images below, where I randomly chose 10,000 points inside an equilateral triangle two ways. The top image uses "naive" barycentric coordinates (using $(x_1,x_2)=u⋅A+v⋅B+w⋅C$), the bottom image uses the weights provided by ChatGPT (using $(x_1,x_2)=(1−\sqrt{r_1})A+\sqrt{r_1}r_2B+\sqrt{r_1}(1-r_2)C$).

As you can see, both point sets "fill" the triangle, but the weighted approach (seems to) do it using a distribution that is uniform over the area, while the naive approach does not (see below image for further discussion).

As can be seen, the naive approach is denser in the center than in the corners. That's because values near the corners can only be obtained when one of $u,v,w$ is very near to $1$, necessitating both other values to be very small. That happens rarely. Points near the triangles center however, mean all 3 values need to be roughly the same, so near $\frac13$.

Since $u,v,w$ cannot be directly obtained using a random uniform distribution for all 3 (the sum would not be $1$), they need to be scaled. Considering that, it makes sense that (before scaling) 3 uniform random variables in $[0,1)$ are more likely to be "roughtly equal" than "one of them is much larger than both others".

Coming back to why square roots are used, which one commenter found unfamiliar. That can be explained in another scenario, that I recently had to implement: Choose a point randomly from a disc (circle with interior).

If the circle's radius is $R$, with center at $(x_M, y_M)$, then the "naive" approach is to choose a factor $u$ uniform random in $[0,1]$ and an angle $\theta$ uniform random in $[0,2\pi]$. Then the point $$(x_M + uR\cos(\theta), y_M + uR\sin(\theta))$$ seems to be a good choice for a random point inside the disc.

However, it's easy to see that those points are not evenly distributed on the disc! That's because with the above algorithm, you will get values of $r=uR$ between $0$ and $\frac{R}2$ roughly half of the time. But they all lie inside the circle around the center with radius $\frac{R}2$, which covers just a quarter of the original circle! As in the triangle case, the points or more dense in the center of the circle than near the circle itself.

In this example, the "fix" is easy: You want $\frac12$ of the points to lie in a circle of half the area of the original circle, which has radius $\frac1{\sqrt2}R$, and $\frac1{\sqrt2} = \sqrt{\frac12}$. So what you need to do is not to use the $uR$ as as your radius, but $\sqrt{u}R$. That way the radius gets "streched" with respect to $uR$, making it give you points that are equally dense in every part of the circle.

This can motivate the use of square roots in the weighted formula. It's not a mathematical proof, but personally I would use the forumula aftera few more tests with other shapes (which I did, and they all were satisfactory for me).