Here is my Soft-Answer to a Soft-Question.

SUMMARY : Cyclic Polynomials are not enough to generate all necessary terms with 4 or more variables.

When we have the given inequality , we eventually want to make it something like $(\cdots f(\text{n-variables}) \cdots)^2$ which must be at least $0$

In general , when we expand the Square & move the terms around , we will get the given inequality. This is high-level & overly-abstract & hand-wavey.

Now , when we have $0,1,2$ variables , Elementary Arithmetic & Differential Calculus will give Direct Answer & we have no necessity of Cyclic Polynomials.

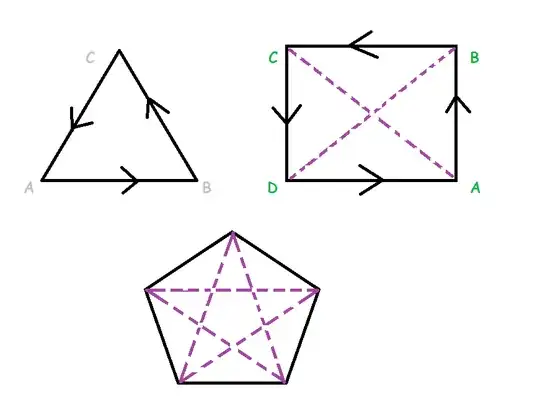

Consider 3 variables :

It will be like $(1+a+b+c)^2$ : where-ever necessary , we can include some Constant & Co-Efficient Eg $(2+3a+6b+9c)^2$ which I will ignore to keep it easy to visualize.

Expanding the Square , we will get 10 terms which we can club easily , $1+\Sigma a + \Sigma ab + \Sigma a^2$ , involving Cyclic Polynomials.

The Cyclic Polynomial occurs because every way to connect 2 variables occurs in the Cycle.

It will still work when we raise to Power 4 or 6.

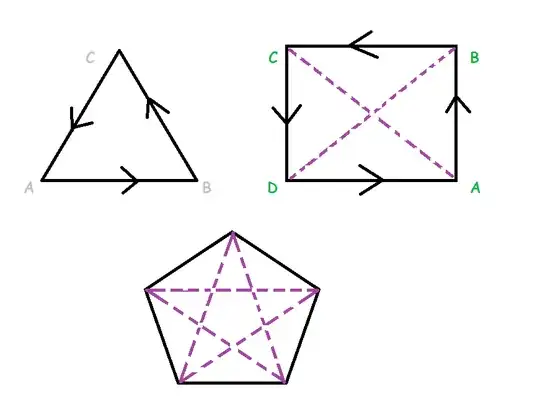

Consider 4 variables :

It will be like $(1+a+b+c+d)^2$ : where I will ignore some Constant & Co-Efficient to keep it easy to visualize.

Expanding the Square , we will get 15 terms which we can try (unsuccessfully) to club , $1+\Sigma a + \color{red}{\Sigma ab} + \Sigma a^2$ , involving Cyclic Polynomials.

The Cyclic Polynomial is not enough because not every way to connect 2 variables occurs in the Cycle.

We will only get $ab,bc,cd,da$

We will not get $ac,db$

When we have 5 or more variables , more terms will be missing in the Cycle.

Hence Cyclic Polynomials are not enough.

Even more terms will be missing when we raise to Power 4 or 6.

In the Summations , we will have to use some thing more , that is , "all combinations of 2 variables" & "all combinations of 3 variables" & "all combinations of 4 variables" . . . .

SUMMARY : Cyclic Polynomials are not enough to generate all necessary terms with 4 or more variables.

When going beyond 3 variables , Cyclic Polynomial are no longer enough & we have to use Symmetric Sum Notation , which has a vast collection of theorems & Exercises . . . .