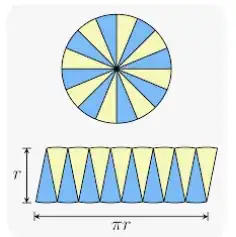

Take a hemisphere and divide its surface area into strips like on a watermelon. Each strip can be approximated as a triangle with the long two sides = $\pi \frac r2$ (quarter of circumference) and if they are laid out and rotated $180$ degrees alternatively to form a rectangle with sides $\pi\frac r2$ and $\pi r$ like in the derivation of the circle's area. Then the area of the full sphere comes out to $\pi^2r^2$. what is wrong here?

Asked

Active

Viewed 124 times

1

-

Please clarify your specific problem or provide additional details to highlight exactly what you need. As it's currently written, it's hard to tell exactly what you're asking. – Community Nov 30 '23 at 16:34

-

This Q is hard to read. Hence, consider to visit MathJax basic tutorial and quick reference for format improvement. – Anton Vrdoljak Nov 30 '23 at 16:39

-

1This is very likely an instance of the staircase paradox. There are duplicates on this site. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Staircase_paradox – Ethan Bolker Nov 30 '23 at 16:40

-

2Does this answer your question? It's not an exact duplicate but I think the principle is the same. Why can't we derive the formula for surface area of a sphere thus? – Ethan Bolker Nov 30 '23 at 16:49

-

1Triangles in spherical geometry have the property that their angles add to more than 180 degrees due to something called positive Gaussian curvature – Leonidas Lanier Nov 30 '23 at 16:56

-

It's impossible to use your method with spherical triangles. – Intelligenti pauca Nov 30 '23 at 17:03

-

I think this is a great question. IMO the moral of the story is that the "thin pizza-slices are basically triangles" proof that the area of a circle is $\pi r^2$ is seriously incomplete as it's usually presented. Approximation arguments require justification that the approximation really does approximate what you're trying to calculate, and in this case with a sphere that step is just false. – Izaak van Dongen Nov 30 '23 at 19:11

-

@IzaakvanDongen The problem is that spherical slices are not triangles, and they overlap when put one near to the other. Hence one cannot use the same argument as in the case of a circle. – Intelligenti pauca Dec 01 '23 at 16:51

-

@Intelligentipauca, I think we agree! Maybe we're looking from different directions - it depends how you interpret things. I'm reading it as "slice up the hemisphere, then take identical isosceles triangles with leg length $\pi r/2$ and base lengths totalling $2\pi r$ and work out the total area". My point is that in the case of a disc, the thin slices' areas are approximated well by taking such triangles (even though the slices aren't triangles), but in the case of a hemisphere they are not approximated well. I agree there are other problems - eg "if they are laid out" is a problematic step. – Izaak van Dongen Dec 01 '23 at 17:13

2 Answers

3

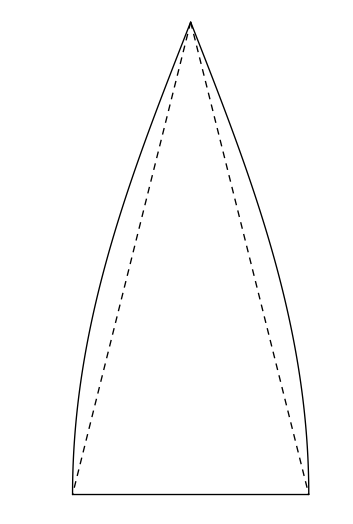

If you could lay down on a plane your strip with lateral sides of length ${\pi\over2}r$ and base $b$, then you would find it isn't a triangle, but rather a figure as shown below. At a distance $h$ from the base its width is $b\cos(h/r)$, hence a simple integral gives its area as $rb$, instead of ${\pi\over4}rb$.

This ratio of ${\pi\over4}$ between the two areas is exactly the ratio between your result $\pi^2r^2$ (for the area of the sphere) and the right one.

Intelligenti pauca

- 55,765

1

Comment only.

Not clear. You wanted to extend to 3d from the following 2d situation? May be Pappu's thm would help if location of CG is known.

Narasimham

- 42,260