I am posting this as an answer because of the length constraint in the comments.

So, I found out the deal here. Basically, I came across this idea while trying to prove the following:

Every closed subspace of a normal space is normal.

To prove this, observe that if $A \subseteq X$ where $(X, \mathcal{T})$ is a normal topological space and if $C, D \subseteq A$ are closed and disjoint in $A$ then they are also closed in $X$. So we can separate them by $U$ and $V$ in $X$ (as $X$ is normal). But then $U\cap A$ and $V \cap A$ are the separating and disjoint open sets in $A$.

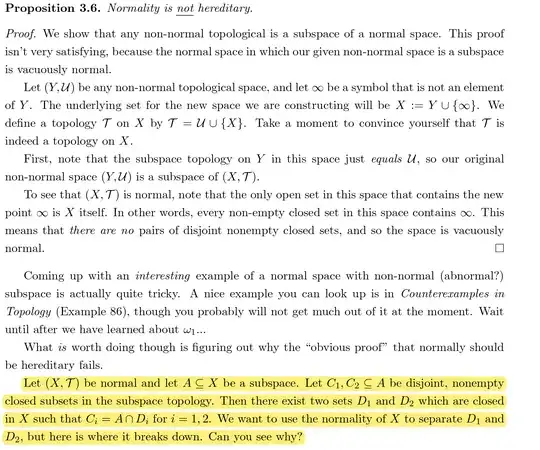

Now coming back to my question. In my question $A$ need not be closed. So, $C$ and $D$ need not be closed in $X$. But normality is for separating closed sets from themselves. So, what are we even trying to separate?