You want $$

\lim_{x \to +\infty} \frac{1}{1-e^{-\frac 1{e^x}}} - e^x - \frac 12

$$

Setting $e^x = t$, note that $t \to +\infty$ as $x \to +\infty$. Therefore, $$

\lim_{x \to +\infty} \frac{1}{1-e^{-\frac 1{e^x}}} - e^x - \frac 12 = \lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{1-e^{-1/t}} - t-\frac 12.

$$

Let $u = 1-e^{-\frac 1t}$. Then, $e^{-\frac 1t} = 1-u$ and hence $\frac {-1}{\ln(1-u)} = t$. Hence, as $t \to +\infty$, $\ln(1-u) \to 0^-$, hence $u \to 0^+$. Therefore, $$

\lim_{t \to \infty} \frac{1}{1-e^{-1/t}} - t-\frac 12 = \lim_{u \to 0^+} \frac 1u +\frac{1}{\ln(1-u)} - \frac 12=\lim_{u \to 0^+} \frac{\ln(1-u)+u}{u\ln(1-u)} - \frac 12 \\

= \lim_{u\to 0^+} \frac{\ln(1-u)-(-u)}{u^2}\frac{u}{\ln(1-u)} -\lim_{ u \to 0^+} \frac 12

$$

By the Taylor expansion of $\ln(1-u)$ near $u=0$, the limit of the first term equals $\frac 12 \times 1 = \frac 12$. Hence, the limit of the entire expression equals $0$, as desired.

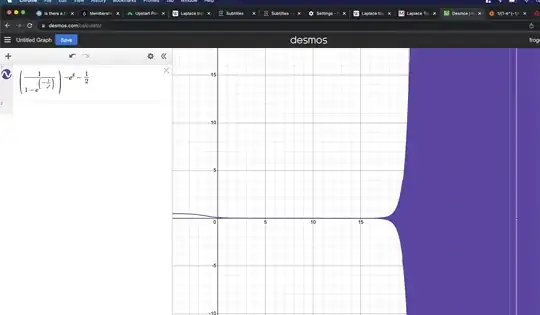

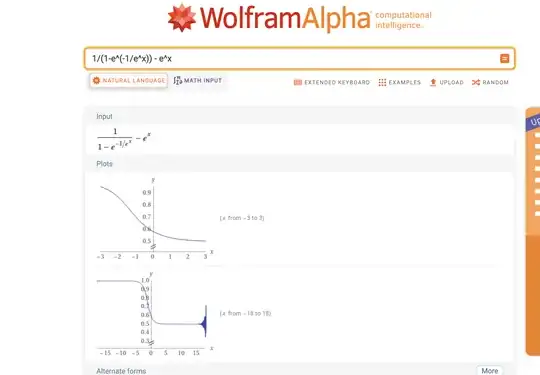

It is impossible that the function in question can oscillate. By the derivative test, the the derivative of $\frac{1}{1-e^{-1/t}} - t - \frac 12$ is negative, which implies that the function is monotonically decreasing as $t \to +\infty$.

Therefore, any authentic enough rendering of the function at those values clearly requires monotonicity to be respected. As a comment points out, just because a function is oscillatory in a particular interval doesn't mean that it cannot have a limit. However, in this case the function cannot be oscillatory anywhere, and yet is shown to be precisely that on a particular interval, proving the inaccuracy of the graphs.

The oscillating behavior has to do with small value floating point errors, which are compounded by various operations. Namely, small enough values are set to $0$ by Wolfram Alpha.

In this case, the small values in question arise from the term $1-e^{-\frac 1{e^x}}$ which is going to $0$. When this value is extremely close to $0$, it cannot be approximated accurately. What happens is that, instead of computing this quantity, we end up computing $$

1+\delta-e^{-\frac 1{e^{x}}},

$$

where $\delta$ is some truncation error. Given the true value of $x$, if one changes $x$ to $x+h$ then the value of this function changes roughly by $he^{-x-e^{-x}}$ by the MVT. Thus, $\delta = he^{-x-e^{-x}}$ which implies that $h = \delta e^{x+e^{-x}}$.

This shows that even if the truncation error is small, the function $1+\delta-e^{-\frac 1{e^{x}}}$ ends up looking like its value not at the point $x$ but rather at the point $x+h$ where $h$ is something exploding as $x \to \infty$ (if $\delta$ can be lower bounded away from $0$, which is generally the case depending upon the values of $x$ in consideration). Furthermore, note that $\delta$ can take positive or negative values depending upon the $x$ in consideration.

Furthermore, we are following up this error by taking the reciprocal of the function. Note that the reciprocal amplifies the sign issue, because $\frac 1y$ has the same sign as $y$ but also a much larger magnitude if $y$ has a small magnitude. Therefore, the error propagates to the reciprocal, but it is much more amplified. Roughly speaking, what happens is that the reciprocal obtained by Wolfram Alpha is not that obtained by actual evaluation at $x$, but rather at some point $x+h$, where $h$ depends on $x$ in such a way that $|h|$ probably goes to infinity as $x$ goes to infinity. Adding in the fact that $h$ may take positive or negative values unboundedly and the nature of the oscillation becomes clearer. Note that $e^x$ should also be carrying errors, but these are of smaller magnitude than that of the reciprocal term. The reciprocal term is the one doing the damage in both graphs.

Another example of how small terms cause damage is when you take the same limit pattern and plot the function $\frac{e^{-x}}{(1-e^{-1/e^x})} - 1$, which has limit $0$. This function will begin to oscillate due to errors, even quicker than the previous one. That's because there's not one small term here in consideration, but two small terms, since $e^{-x}$ is also very small and poorly approximated for $x$ large. These errors compound and make the apparent behavior of the function even worse than the previous situation, despite the limit still being equal to $0$.

Perhaps the lesson here is that we cannot always deduce limit behaviors from plots : instead, we must either seek to reduce inflammatory expressions by substitution (since this doesn't affect limit behavior) or, in our algorithms, must ensure that most errors are "benign" rather than "catastrophic", so that the graphs are easier to interpret. The former is a way out here, since the substitution of $t = e^x$ instantly makes the limit behavior clearer from a graphic point of view (until you hit something like $t = 10000$ and see the oscillations again, that is).