doesnt $f:\mathbb{R}\to\mathbb{Z}$ mean that $f$ maps every real $x$, to a unique integer $y$? That doesn't imply that that $f$ maps every real $x$, to a unique real $y$, right?

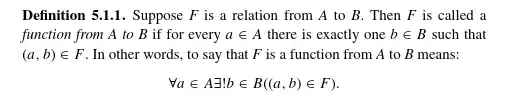

Here is how the book im reading defines a function:

But even if $B\subseteq C$, in my opinion $\forall a\in A\exists!b\in B((a,b)\in F)$ doesn't automatically imply $\forall a\in A\exists!c\in C((a,c)\in F)$

Example:

$A=\{1\}$, $B=\{8\}$, $C=\{8,9\}$

$f=\{(1,8),(1,9)\}$

By the definition above, $f:A\to B$, but not $f:A\to C$, even though $B\subseteq C$