Consider the following question

Let $D_1$ and $D_2$ be two overlapping closed discs. Let $f$ be a holomorphic function on some open neighborhood of $D = D_1 \cap D_2$. Show that there exist open neighborhoods $U_j$ of $D_j$ and holomorphic functions $f_j$ on $U_j$ for $j = 1, 2$, such that $f(z) = f_1(z) + f_2(z)$ on $U_1 \cap U_2$.

I am convinced that this is not necessarily true. Here is my counter-example:

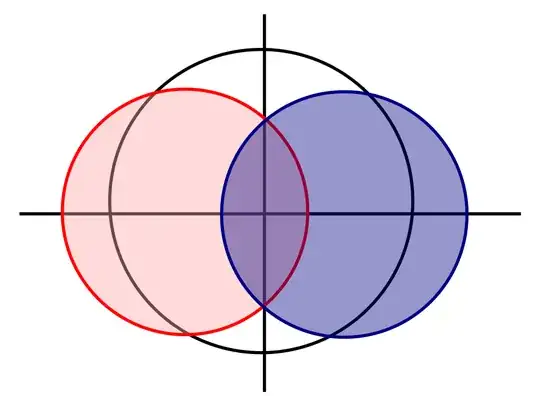

Let $D_1$ and $D_2$ be the red and blue circles in the bellow diagram. Morever, let the black one be the unit disc.

Let

$$

f(z) = \sum_{n=1}^\infty z^{2^n}.

$$

Per this question, the function does not have an analytic continuation that contains any part of the unit circle. Now, in the question, by the identity theorem, we must have

$$

f_1 = f_2 = \frac{1}{2}f

$$

on $D$. As $f_1$ is holomorphic on $U_1$, it is holomorphic on $D_1$. But this together with the identity theorem on $D_1 \cap D$ gives us that $f$ can be analytically extended through the unit circle, which can not be true.

Let

$$

f(z) = \sum_{n=1}^\infty z^{2^n}.

$$

Per this question, the function does not have an analytic continuation that contains any part of the unit circle. Now, in the question, by the identity theorem, we must have

$$

f_1 = f_2 = \frac{1}{2}f

$$

on $D$. As $f_1$ is holomorphic on $U_1$, it is holomorphic on $D_1$. But this together with the identity theorem on $D_1 \cap D$ gives us that $f$ can be analytically extended through the unit circle, which can not be true.

Question: Is my counter example correct?