I don't usually post empirical results as an answer, but I find it difficult to see how to make analytical progress.

Claim. (Additive basis of order 2) Every positive integer can be written in the form $\lfloor m^q\rfloor+\lfloor n^q\rfloor$ for some positive integers $m\le n$.

The difficulty lies in the difference that you request "every positive integer" instead of "every sufficiently large positive integer". The latter phrase is easier as we can make (sometimes quite crude) number-theoretic bounds to arrive at the result. As noted in the comments, several publications have resolved the claim for various ranges of $q$.

In the "sufficiently large" case, these include:

$q\in(1,3/2)$: Konyagin, S.V., 2002. An additive problem with fractional powers.

$q\in(1,11/10)$ when one of $m,n$ is prime: Yu, G., 2020. On a binary additive problem involving fractional powers. Journal of Number Theory, 208, pp.101-119.

Your post has two questions:

- Does the claim hold when $q=5/4$?

- What is $\sup q$ such that the claim holds?

For empirical results, I will look at the smallest positive integer that cannot be written in said form with $n$ given.

- The R code to compute the smallest positive integer is as follows.

floorfunc <- function(q,a){

p <- array(NA,c(a,a))

for(m in 1:a){for(n in 1:a){p[m,n] <- floor(m^q)+floor(n^q)}}

return(sort(setdiff(2:p[a,a],unique(as.vector(p))))[1])}

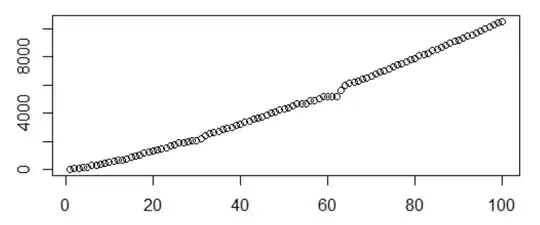

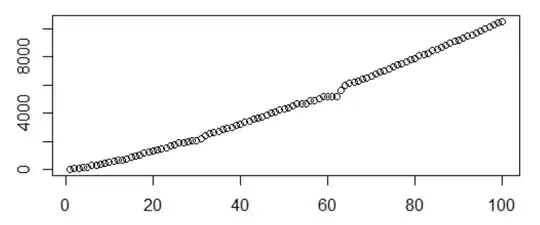

The horizontal axis in the plot is $n/10$ and the vertical axis is the smallest positive integer.  The growth rate is slowly exponential, and with Konyagin's result, it makes sense to believe the claim holds.

The growth rate is slowly exponential, and with Konyagin's result, it makes sense to believe the claim holds.

- I believe $$\sup q=1.26966\cdots$$ (note this does not appear in OEIS). The following function calculates the smallest non-representable positive integer as $q$ increments from $a+b/100$ to $a+b$ in increments of $1/100$, when $n=200$.

floorarray <- function(a,b){

r <- array(NA,100)

for(k in 1:s){r[k] <- floorfunc(a+b*k/100,200)}

return(r)}

When $a=b=1$, we observe a very apparent drop in the $27$th element; that is, $q=1.27$. This means that $31$ cannot be written as $\lfloor m^{1.27}\rfloor+\lfloor n^{1.27}\rfloor$.

[1] NA NA NA 493 NA NA NA 609 639 675 661 705 743 757

[15] 790 835 874 876 967 1032 1055 1115 1097 1254 1330 1387 31 1544

[29] 30 17 15 13 13 11 11 11 9 9 9 9 7 7

[43] 7 7 7 7 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5

[57] 5 5 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

[71] 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

[85] 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3

[99] 3 3

With this knowledge, narrowing the interval $(a+b/100,a+b)$ repeatedly leads to the interval $(1.26966+0.00004/100,1.26967)$, in which we obtain

[1] 1375 1375 1375 1375 1375 1375 1375 1375 1375 1375 1375 31 31 31

[15] 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

[29] 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

[43] 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

[57] 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

[71] 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

[85] 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31 31

[99] 31 31