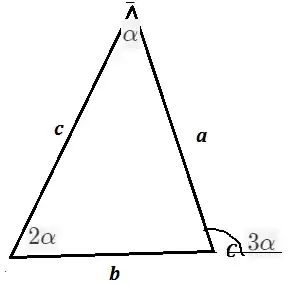

Consider the triangle ABC in which $AC(AB+ AC)={BC}^{2}$ Show that angles $BAC = 2\cdot ABC$.

MY IDEAS

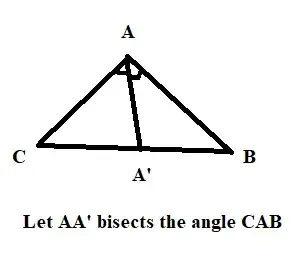

MY DRAWING

So I processed the equality that was given

$AC(AB+ AC)={BC}^{2}$

$AC=\frac{{BC}^{2}}{AB+AC}$

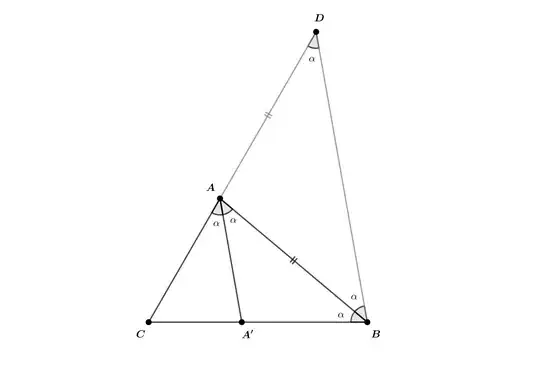

As you can see, I put a point AA' that bisects the angle CAB. I will apply the bisector theorem in triangle CAB with the bisector AA'.

$\frac{BA'}{A'C}=\frac{AB}{AC}$

$\frac{BA'+A'C}{A'C}=\frac{AB+AC}{AC}$

$\frac{BC}{A'C}=\frac{AB+AC}{AC}$

$AB+AC=\frac{BC\cdot AC}{A'C}$

Then we are switching $AB+AC$ with what we discover it equals.

${AC}^{2}\cdot BC={BC}^{2}\cdot A'C$

$AC=\sqrt{BC\cdot A'C}$

This seems like the reciprocal of the leg theorem. I don't know what to do forward.

All ideas are welcome. Hope one of you can help me. Thank you!