Proof.

We need to prove that, for all $x, y, z > 0$ with $x + y + z = \pi$,

$$8\sin x \sin y \sin z \cdot \ln (2\sin x) \cdot \ln(2 \sin y) \cdot \ln(2\sin z) > -\ln 2. \tag{1}$$

We only need to prove the case that

$\ln (2\sin x) \cdot \ln(2 \sin y) \cdot \ln(2\sin z) < 0$.

We split into two cases.

Case 1: $\ln(2\sin x) < 0, \ln(2\sin y) < 0, \ln(2\sin z) < 0$

It is easy to prove that

$-\mathrm{e}^{-1} \le u\ln u < 0$ for all $u\in (0, 1)$. Thus, we have

$-\mathrm{e}^{-1} \le 2\sin x \ln(2\sin x) < 0$ etc. and

$$\mathrm{LHS} \ge (-\mathrm{e}^{-1})^3 > -\ln 2.$$

$\phantom{2}$

Case 2: $\ln(2\sin x) > 0, \ln(2\sin y) > 0, \ln(2 \sin z) < 0$

We have $x, y \in (\pi/6, 5\pi/6)$

and $z \in (0, \pi/6)$.

Note that $x\mapsto \ln (2\sin x)$ is concave on $(\pi/6, 5\pi/6)$.

We have

$$\ln(2\sin x) + \ln(2\sin y)

\le 2\ln\left(2\sin \frac{x + y}{2}\right). \tag{2}

$$

Using (2), we have

$$2\sin x \cdot 2\sin y \le \left(2\sin \frac{x + y}{2}\right)^2. \tag{3}$$

By AM-GM, using (2), we have

$$

\ln(2\sin x) \ln (2\sin y)

\le \frac14[\ln(2\sin x) + \ln(2\sin y)]^2\le \ln^2\left(2\sin \frac{x + y}{2}\right). \tag{4}$$

From (1), (3) and (4), it suffices to prove that

$$ \left(2\sin \frac{x + y}{2}\right)^2\cdot \ln^2\left(2\sin \frac{x + y}{2}\right) \cdot 2\sin z \cdot

\ln(2\sin z) > -\ln 2$$

or

$$ \left(2\cos\frac{z}{2}\right)^2\cdot \ln^2\left(2\cos \frac{z}{2}\right) \cdot 2\sin z \cdot

\ln(2\sin z) > -\ln 2$$

or

$$\ln^2 2 > \left(2\cos\frac{z}{2}\right)^4\cdot \ln^4\left(2\cos \frac{z}{2}\right) \cdot 4\sin^2 z \cdot \ln^2(2\sin z)$$

or

$$\ln^2 2 > (2 + 2\cos z)^2 \cdot \frac{1}{2^4}\ln^4 (2 + 2\cos z)\cdot

4(1 - \cos^2 z)\cdot \frac{1}{2^2}\ln^2(4 - 4\cos^2 z)$$

where we use

$4\cos^2 \frac{z}{2} = 2 + 2\cos z$.

Letting $u = \cos z$, it suffices to prove that, for all $\frac{\sqrt 3}{2} < u < 1$,

$$\ln^2 2 > (2 + 2u)^2 \cdot \frac{1}{2^4}\ln^4 (2 + 2u)\cdot

4(1 - u^2)\cdot \frac{1}{2^2}\ln^2(4 - 4u^2) \tag{5}$$

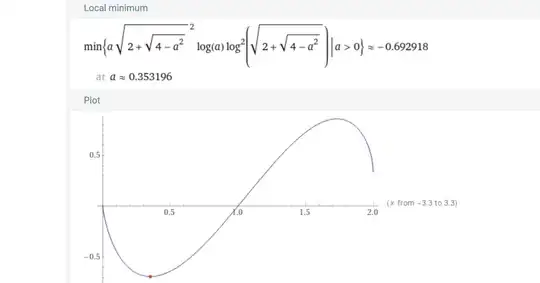

which is true. The proof is given at the end.

We are done.

$\phantom{2}$

Proof of (5):

Using $\frac{64}{63}u^2 + \frac{63}{64} - 2u = \frac{1}{4032}(64u-63)^2 \ge 0$, we have

$$(2 + 2u)^2 = 4 + 4u^2 + 8u \le 4 + 4u^2 + 4\left(\frac{64}{63}u^2 + \frac{63}{64}\right) .$$

It suffices to prove that

$$\ln^2 2

> \frac{1}{256}\left(\frac{508}{63}u^2 + \frac{127}{16}\right)\ln^4 \left(\frac{508}{63}u^2 + \frac{127}{16}\right) \cdot (1 - u^2)\ln^2(4 - 4u^2). \tag{6}$$

Letting $4 - 4u^2 = v$, it suffices to prove that, for all $v \in (0, 1)$,

$$\ln^2 2 > \frac{1}{1024}\left(\frac{16129}{1008} - \frac{127}{63}v\right) \ln^4 \left(\frac{16129}{1008} - \frac{127}{63}v\right) \cdot v\ln^2 v. \tag{7}$$

We can prove that, for all $v\in (0, 1)$,

$$v\ln^2 v \le \frac98\ln^2 2 + (9\ln^2 2 - 6\ln 2)(v - 1/8). \tag{8}$$

(Note: The RHS is the first order Taylor approximation of LHS around $v = 1/8$. Proof: Take derivative.)

We can also prove that, for all $v\in (0, 1)$,

$$\ln \left(\frac{16129}{1008} - \frac{127}{63}v\right)

\le \ln\frac{15875}{1008} - \frac{16}{125}(v - 1/8). \tag{9}$$

(Note: The RHS is the first order Taylor approximation of LHS around $v = 1/8$. Proof: Take derivative.)

It suffices to prove that, for all $v\in (0, 1)$,

\begin{align*}

\ln^2 2 &> \frac{1}{1024}\left(\frac{16129}{1008} - \frac{127}{63}v\right) \left[\ln\frac{15875}{1008} - \frac{16}{125}(v - 1/8)\right]^4\\[10pt]

&\qquad \times \left[\frac98\ln^2 2 + (9\ln^2 2 - 6\ln 2)(v - 1/8)\right]. \tag{10}

\end{align*}

Using $\ln\frac{15875}{1008} < \frac{397}{144}$, it suffices to prove that

for all $v\in (0, 1)$,

\begin{align*}

\ln^2 2 &> \frac{1}{1024}\left(\frac{16129}{1008} - \frac{127}{63}v\right) \left[\frac{397}{144} - \frac{16}{125}(v - 1/8)\right]^4\\[10pt]

&\qquad \times \left[\frac98\ln^2 2 + (9\ln^2 2 - 6\ln 2)(v - 1/8)\right]

\end{align*}

or

\begin{align*}

1 &> \frac{1}{1024}\left(\frac{16129}{1008} - \frac{127}{63}v\right) \left[\frac{397}{144} - \frac{16}{125}(v - 1/8)\right]^4\\[10pt]

&\qquad \times \left[\frac98 + \left(9 - \frac{6}{\ln 2}\right)(v - 1/8)\right]. \tag{11}

\end{align*}

We split into two cases.

Case 1: $0 < v \le 1/8$

Using $\ln 2 > \frac{70}{101}$, it suffices to prove that

\begin{align*}

1 &> \frac{1}{1024}\left(\frac{16129}{1008} - \frac{127}{63}v\right) \left[\frac{397}{144} - \frac{16}{125}(v - 1/8)\right]^4\\[10pt]

&\qquad \times \left[\frac98 + \left(9 - \frac{6}{70/101}\right)(v - 1/8)\right].\tag{12}

\end{align*}

Letting $v = \frac{1}{8 + w}$ for $w \ge 0$, (12) is written as

$$\frac{F(w)}{10113169489920000000000000(8+w)^6} > 0$$

where

\begin{align*}

F(w) &= 2416264063255035327931w^6 + 53231769508888881467040w^5\\

&\qquad + 440259554245249137560000w^4 + 4667308406207884160000000w^3\\

&\qquad + 67053001632350760000000000w^2 + 463246417085920000000000000w\\

&\qquad + 1111827500508480000000000000.

\end{align*}

Thus, (12) is true.

Case 2: $1/8 < v < 1$

Using $\ln 2 < \frac{61}{88}$, it suffices to prove that

\begin{align*}

1 &> \frac{1}{1024}\left(\frac{16129}{1008} - \frac{127}{63}v\right) \left[\frac{397}{144} - \frac{16}{125}(v - 1/8)\right]^4\\[10pt]

&\qquad \times \left[\frac98 + \left(9 - \frac{6}{61/88}\right)(v - 1/8)\right]. \tag{13}

\end{align*}

Letting $v = \frac{1 + 8w}{8 + 8w}$ for $w > 0$, (13) is written as

$$\frac{G(w)}{17625809682432000000000000(1+w)^6} > 0$$

where

\begin{align*}

G(w) &= 823425037465312092776856w^6 + 3524126527531263109253089w^5\\

&\qquad +5778219879301331456143375w^4+4426205206524727153031250w^3\\

&\qquad +1504381676597156324218750w^2+163085374636585205078125w\\

&\qquad +7391954425377685546875.

\end{align*}

Thus, (13) is true.

We are done.