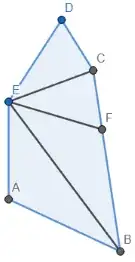

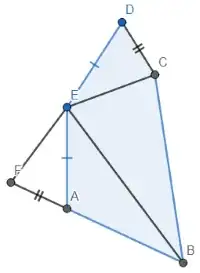

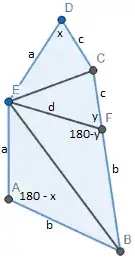

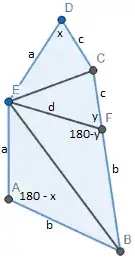

You've made a good start. We can prove $EF = ED = AE\;$ by using the law of cosines on several triangles and that $\cos(180^{\circ}-z)=-\cos(z)$. First, for somewhat simpler algebra, I've assigned several angle and length values as shown in the diagram below:

In particular, there's

$$AE=ED=a, \; AB=BF=b, CF=CD=c, EF=d, \measuredangle CDE = x, \measuredangle CFE = y \tag{1}\label{eq1A}$$

Thus, $\measuredangle BAE = 180^{\circ} - x$ and $\measuredangle BFE = 180^{\circ} - y$. Using the law of cosines for the common side of $EB$ in $\triangle EAB$ and $\triangle EFB$, we get

$$\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

EB^2 & = a^2 + b^2 + 2ab\cos(x) \\

& = b^2 + d^2 + 2bd\cos(y)

\end{aligned}\end{equation}\tag{2}\label{eq2A}$$

The first line subtract the second line gives

$$a^2-d^2 +2b(a\cos(x) - d\cos(y)) = 0 \tag{3}\label{eq3A}$$

Next, using the law of cosines for the common side of $EC$ in $\triangle EDC$ and $\triangle EFC$ gives

$$\begin{equation}\begin{aligned}

EC^2 & = a^2 + c^2 - 2ac\cos(x) \\

& = c^2 + d^2 - 2cd\cos(y)

\end{aligned}\end{equation}\tag{4}\label{eq4A}$$

As before, the first line subtract the second line gives

$$a^2 - d^2 - 2c(a\cos(x) - d\cos(y)) = 0 \tag{5}\label{eq5A}$$

Next, \eqref{eq3A} subtract \eqref{eq5A} gives, since $b \gt 0$ and $c \gt 0$, that

$$2(b+c)(a\cos(x)-d\cos(y)) = 0 \; \; \to \; \; a\cos(x)-d\cos(y) = 0 \tag{6}\label{eq6A}$$

Substituting this in either \eqref{eq3A} or \eqref{eq5A}, and using \eqref{eq1A}, gives

$$a^2 - d^2 = 0 \; \; \to \; \; a = d \; \; \to \; \; EF = ED = AE \tag{7}\label{eq7A}$$