INTRODUCTION TO QUESTION 1

Some authors proposed a tensorial representation of complex networks (for both single layer networks and multilayer networks). One reference paper for this topic is this one:

(note: the same tensorial representation of complex networks was treated also in the section "2.1 Tensorial Representation of a Complex Network" of a recent book: O. Artime et al., Multilayer Network Science: From Cells to Societies. Elements in Structure and Dynamics of Complex Networks (2022))

I rewrite here a few sentences from that paper (which basically come from the beginning of the section ``II. SINGLE-LAYER (MONOPLEX) NETWORKS''), to introduce and better understand my questions.

- Given a set of $N$ objects $n_i$ (where $i=1,2,...,N$ and $N \in \mathbb{N}$), we associate with each object a state that is represented by a canonical vector in the vector space $\mathbb{R}^N$.

- More specifically, let $\mathbf{e}_{i} \equiv (0,...,0,1,0,...,0)^\mathsf{T}$, where $\mathsf{T}$ is the

transposition operator, be the column vector that corresponds to the

object $n_i$ (which we call a node).- The $i$th-component of $\mathbf{e}_{i}$ is $1$, and all of its other components are $0$.

- One can relate the objects $n_i$ with each other, and our goal is to find a simple way to indicate the presence of the intensity of such relationships.

- The most natural choice of vector space for describing the relationship is created using the tensor product (i.e. the Kronecker product) $\mathbb{R}^N \otimes \mathbb{R}^N = \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}$.

- Thus, second order (i.e., rank-2) canonical tensors are defined by $\mathbf{E}_{ij} = \mathbf{e}_{i} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{j}^\mathsf{T}$, where $i,j=1,2,...,N$.

- Consequently, if $w_{ij}$ indicates the intensity of the relationship from object $n_i$ to object $n_j$, we can write the relationship tensor as: $\mathbf{W} = \sum_{i,j=1}^N w_{ij} \mathbf{E}_{ij} = \sum_{i,j=1}^N w_{ij} \mathbf{e}_{i} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{j}^\mathsf{T}$, where $\mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^N \otimes \mathbb{R}^N$.

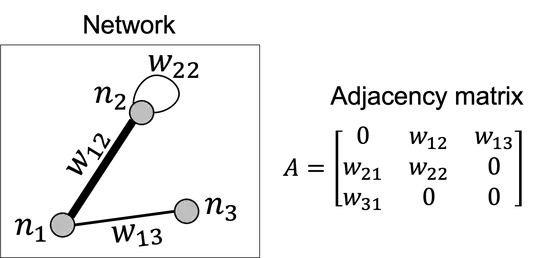

Note for people who are not familiar with complex networks. Basically, the matrix representation of the relationship tensor $\mathbf{W}$ would be the so-called adjacency matrix, used in the field of complex networks to indicate where edges are present among nodes, and also, to indicate the strength/intensity of those edges, just using the object $w_{ij}$. For example, the adjacency matrix of this tiny network, composed of three nodes (indicated by $n_1$, $n_2$ and $n_3$), is the following:

Therefore, in this example, the relationship tensor $\mathbf{W}$ would be written as follows:

\begin{align} \mathbf{W} &= \begin{aligned}[t] \sum_{i,j=1}^3 w_{ij} \mathbf{e}_{i} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{j}^\mathsf{T} = 0 ( \mathbf{e}_{1} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{1}^\mathsf{T} ) + w_{12} ( \mathbf{e}_{1} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{2}^\mathsf{T} ) + w_{13} ( \mathbf{e}_{1} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{3}^\mathsf{T} ) + w_{21} ( \mathbf{e}_{2} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{1}^\mathsf{T} ) + w_{22} ( \mathbf{e}_{2} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{2}^\mathsf{T} ) + 0 ( \mathbf{e}_{2} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{3}^\mathsf{T} ) + w_{31} ( \mathbf{e}_{3} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{1}^\mathsf{T} ) + 0 ( \mathbf{e}_{3} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{2}^\mathsf{T} ) + 0 ( \mathbf{e}_{3} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{3}^\mathsf{T} ) \end{aligned}\\ &= \begin{aligned}[t] w_{12} \Biggl( \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \otimes \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \Biggr) + w_{13} \Biggl( \begin{bmatrix} 1 \\ 0 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \otimes \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 1 \end{bmatrix} \Biggr) + w_{21} \Biggl( \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \otimes \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \Biggr) + w_{22} \Biggl( \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 1 \\ 0 \end{bmatrix} \otimes \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 1 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \Biggr) + w_{31} \Biggl( \begin{bmatrix} 0 \\ 0 \\ 1 \end{bmatrix} \otimes \begin{bmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \Biggr) \end{aligned}\\ &= \begin{aligned}[t] \begin{bmatrix} 0 & w_{12} & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & w_{13}\\ 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0\\ w_{21} & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & w_{22} & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} + \begin{bmatrix} 0 & 0 & 0\\ 0 & 0 & 0\\ w_{31} & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned}\\ &= \begin{aligned}[t] \begin{bmatrix} 0 & w_{12} & w_{13}\\ w_{21} & w_{22} & 0\\ w_{31} & 0 & 0 \end{bmatrix} \end{aligned} \end{align}

QUESTION 1

As far as I know, a tensor is a combination of vectors and covectors, and it is invariant under a change of basis. Therefore, I would have expected that the tensor $\mathbf{W}$ would have been introduced as a tensorial product of a vector and a covector, both including their components and bases. Instead, to me, it looks like the authors just used the vector and covector bases, i.e. $\mathbf{e}_{i} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{j}^\mathsf{T}$ to define the tensor $\mathbf{W}$, and not the (vector and covector) components as well. And just in a second moment, they added the elements $w_{ij}$ somehow "artificially" to the tensor (indeed, the authors wrote exactly: "Consequently, if $w_{ij}$ indicates the intensity of the relationship from object $n_i$ to object $n_j$"). I explain here better what I would have expected to introduce the tensor $\mathbf{W}$. If we consider a vector $\vec{v}=\sum_i v^i \vec{e_i}$ and a covector $c =\sum_j c_j \epsilon^j$, then, I would introduce $\mathbf{W}$ as follows:

\begin{align} \mathbf{W} &= \begin{aligned}[t] \vec{v} \otimes c \end{aligned}\\ &= \begin{aligned}[t] \sum_{i,j} v^i \vec{e_i} \otimes c_j \epsilon^j \end{aligned}\\ &= \begin{aligned}[t] \sum_{i,j} v^i c_j ( \vec{e_i} \otimes \epsilon^j ) \end{aligned}\\ &= \begin{aligned}[t] \sum_{i,j} w^i_j ( \vec{e_i} \otimes \epsilon^j ) \end{aligned} \end{align}

where:

- $\vec{e_i} \otimes \epsilon^j$ would be the Kronecker product among the basis vector $\vec{e_i}$ and the basis covector $\epsilon^j$, equivalent to what written by the authors, i.e. $\mathbf{e}_{i} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{j}^\mathsf{T}$ (with a sligtly different notation),

- $v^i$ and $c_j$ are the vector components and the covector components, respectively,

- $w^i_j := v^i c_j$ would result from the product between the vector components and the covector components of the "input" vector and covector.

- By introducing $\mathbf{W}$ in this way, I would write the map as follows: $\mathbf{W}: V \otimes V^* \rightarrow \mathbb{R}^N \otimes \mathbb{R}^N$

Therefore, my question(s):

- Is my reasoning about the introduction of the tensor $\mathbf{W}$ wrong, compared to the way the authors did in their paper?

- Or is it a normal procedure to define a tensor just using the second-order (i.e., rank-2) canonical tensor $\mathbf{E}_{ij} = \mathbf{e}_{i} \otimes \mathbf{e}_{j}^\mathsf{T}$, and then add the elements $w_{ij}$ to it ?

- What is the physical meaning of vector and covector, for the authors, in their paper?

INTRODUCTION TO QUESTION 2

In the same section of that paper, just after the introduction of $\mathbf{W}$, the authors added something to the previous definition of $\mathbf{W}$.

- We will use the covariant notation introduced by Ricci and Levi- Civita.

- In this notation, a row vector $\mathbf{a} \in \mathbb{R}^N$ is given by a covariant vector $a_\alpha$ (where $\alpha=1,2,...,N$), and the corresponding contravariant vector $a^\alpha$ (i.e., its dual vector) is a column vector in Euclidean space.

- To avoid confusion, we will use latin letters $i,j,...$ to indicate, for example, the $i$-th vector, the $(ij)$-th tensor, etc., and we will use greek letters $\alpha,\beta,...$ to indicate the components of a vector or a tensor.

- With this terminology, $e^{\alpha}(i)$ is the $\alpha$-th component of the $i$-th contravariant canonical vector $\mathbf{e}_i$ in $\mathbb{R}^N$, and $e_{\alpha}(j)$ is the $\alpha$-th component of the $j$-th covariant canonical vector in $\mathbb{R}^N$.

- With these conventions, the adjacency tensor $\mathbf{W}$ can be represented as a linear combination of tensors in the canonical basis: $W^{\alpha}_{\beta} = \sum_{i,j=1}^N w_{ij} e^{\alpha}(i) \otimes e_{\beta}(j) = \sum_{i,j=1}^N w_{ij} E^{\alpha}_{\beta}(ij)$

- Here, $E^{\alpha}_{\beta}(ij) \in \mathbb{R}^N \times \mathbb{R}^N$ indicates the tensor in the canonical basis that corresponds to the tensor product of the canonical vectors assigned to nodes $n_i$ and $n_j$ (i.e. $\mathbf{E}_{ij}$).

- The adjacency tensor $W^{\alpha}_{\beta}$ is of mixed type: it is 1-covariant and 1-contravariant.

QUESTION 2

Now, I am very confused.

- What is the need to introduce $W^{\alpha}_{\beta}$ after $\mathbf{W}$ ? Was not $\mathbf{W}$ enough to get the adjacency tensor/matrix ?

- What is the the difference between $W^{\alpha}_{\beta}$ and $\mathbf{W}$ ?

- What is the the interpretation of $W^{\alpha}_{\beta}$ (in comparison to $\mathbf{W}$) ?

@eigenchris (or @eigenchris): it would be interesting to know your opinion on this topic as well!