While researching the topic of odd perfect numbers, we came across the following implication, which we currently do not know how to prove:

CONJECTURE: If $p^k m^2$ is an odd perfect number with special prime $p$ and $p = k$, then $\sigma(p^k)/2$ is not squarefree.

Here, $\sigma(x)=\sigma_1(x)$ is the classical sum of divisors of the positive integer $x$. (Note that both $p \equiv k \equiv 1 \pmod 4$ and $\gcd(p,m)=1$ hold.)

OUR ATTEMPT

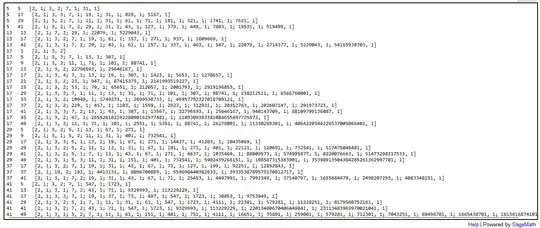

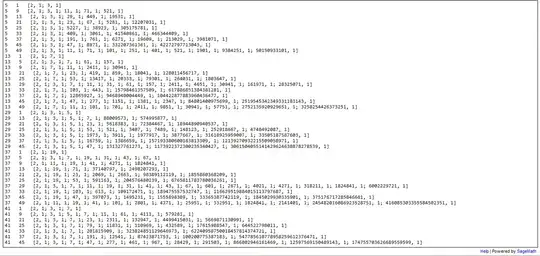

Here are the details of our search in the range $5 \leq p < 50$, $1 \leq k < 50$ using the following Sage Math Cell - Pari-GP scripts:

(1) Searching for examples where $\sigma(p^k)/2$ is not squarefree

for(x=1, 50, for(y=1, 50, if((isprime(x)) && (Mod(x,4) == 1) && (Mod(y,4) == 1) && !(issquarefree(sigma(x^y)/2)),print(x," ",y," ",factor(sigma(x^y))))))

(2) Searching for examples where $\sigma(p^k)/2$ is squarefree

for(x=1, 50, for(y=1, 50, if((isprime(x)) && (Mod(x,4) == 1) && (Mod(y,4) == 1) && (issquarefree(sigma(x^y)/2)),print(x," ",y," ",factor(sigma(x^y))))))

As you can see, the Conjecture does appear plausible. However, computational searches are very far from a complete proof, though they certainly add to the evidence supporting the Conjecture.

Here is our:

QUESTION: Does anybody here have any ideas on how to prove the Conjecture?

for(x=1, 10000, if((isprime(x)) && (Mod(x,4) == 1) && !(issquarefree(sigma(x^x)/2)),print(x)))

and

for(x=1, 10000, if((isprime(x)) && (Mod(x,4) == 1) && (issquarefree(sigma(x^x)/2)),print(x)))

are working flawlessly and as designed, with the second script returning $0$ rows. This gives further computational evidence in support of the Conjecture.

– Jose Arnaldo Bebita Dris Jan 14 '23 at 09:39