I have carefully read the M.S.E. post here explaining the derivation of Taylor series, and I paid attention to the link in one of the comments, i.e., a dedicated blog post on Taylor series.

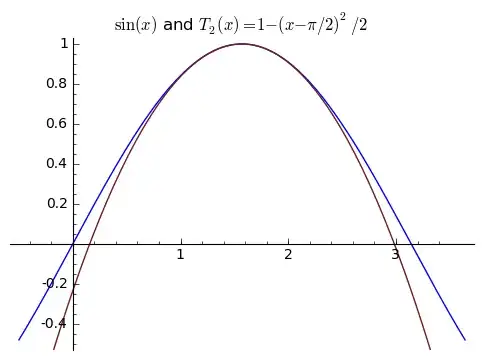

In the linked blog post, the author explains how $\sin(x)$ can be approximated with a Taylor series expansion. Specifically, an example is given for a second-order Taylor approximation (denoted $T_2(x)$) where the expansion is carried around the point $x=\frac{\pi}{2}$: here, the author explains that a curve can be defined using:

- a single point (i.e., $T_2(x=\frac{\pi}{2})=\sin(x=\frac{\pi}{2})=1$)

- the derivative at this point (i.e., we want the approximating polynomial to be $T_2'(x=\frac{\pi}{2})=\sin'(x=\frac{\pi}{2})=0$)

- The “curvature” at the same point, i.e., second derivative ($T_2''(x=\frac{\pi}{2})=\sin''(x=\frac{\pi}{2})=-1)$)

Solving for these conditions gives the following approximation:

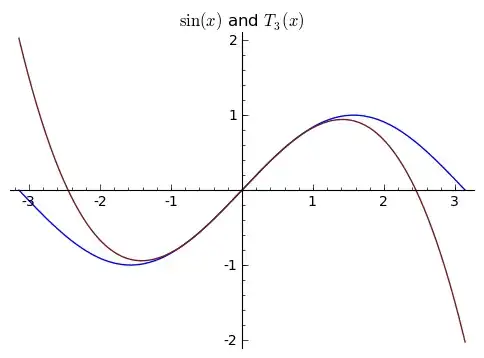

The third-order Taylor approximation, $T_3(x)$ is carried out around $x=0$ (i.e., the inflection point), by adding a condition on the third derivative at $x=0$, in addition to slope and curvature at that point, leading to:

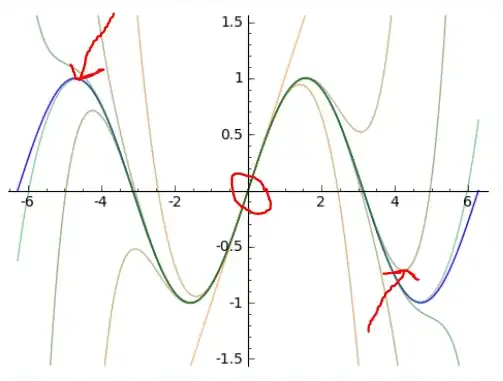

My question: I conceptually understand how the two graphs above can be generated by information at a single point (i.e., $x=\frac{\pi}{2}$ for the first one and $x=0$ for the second one). But how can higher-order derivative terms in the Taylor expansion, all taken at the same point, provide information about local minima and maxima further away from the point of the approximation?

I.e., how can higher-order derivatives taken (say) at $x=0$ see “behind the next turn”?

I try to highlight this at the graph below: I cannot get my head around how information contained at $x=0$ can give the right point for the Taylor approximation at (say) $x=\frac{3\pi}{2}$, for example.