Let us abbreviate $\mathrm{Hom}_ℤ$ and $\mathrm{End}_ℤ$ as $\mathrm{Hom}$ and $\mathrm{End}$ respectively.

Framework

Let us first consider two abelian groups $M$ and $N$.

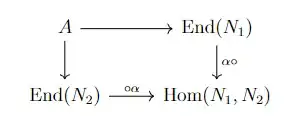

The abelian group $\mathrm{Hom}(M, N)$ becomes a left $\mathrm{End}(N)$-module via postcomposition and a right $\mathrm{End}(M)$-module via precomposition.

For a given element $f$ of $\mathrm{Hom}(M, N)$ we can consider the set

$$

E_f

:=

\{

(h, k) ∈ \mathrm{End}(M) × \mathrm{End}(N)

\mid

h f = f k

\} \,.

$$

This set is a subring of $\mathrm{End}(M) × \mathrm{End}(N)$.

It is also closed under invertibility, in the following sense:

whenever $(h, g)$ is an element of $E_f$ that is invertible in $\mathrm{End}(M) × \mathrm{End}(N)$, its inverse $(h, k)^{-1} = (h^{-1}, k^{-1})$ is again contained in $E_f$.

Observation

The ring $E_f$ helps us understand module structures on $M$ and $N$ for which $f$ is a homomorphism.

Let $B$ be a ring.

A $B$-module structure on $M$ is the same a homomorphism of rings from $B$ to $\mathrm{End}(M)$.

Simultaneous $B$-module structures on $M$ and $N$ are therefore the same as a pair $(φ_1, φ_2)$ of homomorphisms of rings $φ_1 \colon B \to \mathrm{End}(M)$ and $φ_2 \colon B \to \mathrm{End}(N)$.

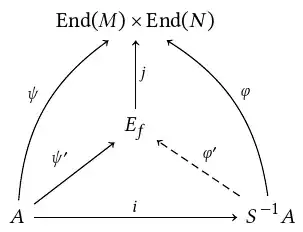

Such a pair of homomorphisms is the same as a single homomorphism $φ \colon B \to \mathrm{End}(M) × \mathrm{End}(N)$ (whose components are given by $φ_1$ and $φ_2$).

The map $f$ is a homomorphism of $B$-modules if and only if the image of $φ$ is contained in the subring $E_f$ of $\mathrm{End}(M) × \mathrm{End}(N)$.

In other words, if and only if there exists a homomorphism of rings $φ' \colon B \to E_f$ such that $φ = j ∘ φ'$, where $j$ is the inclusion map from $E_f$ to $\mathrm{End}(M) × \mathrm{End}(N)$.

The problem at hand

Let us now consider the original problem:

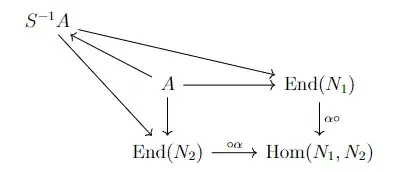

$M$ and $N$ are not just abelian groups, but $S^{-1} A$-modules.

These simultaneous $S^{-1} A$-module structures correspond to a homomorphism of rings $φ \colon S^{-1} A \to \mathrm{End}(M) × \mathrm{End}(N)$.

We can regard $M$ and $N$ as $A$-modules by restriction, and these simultaneous $A$-module structures correspond to a homomorphism of rings $ψ \colon A \to \mathrm{End} × \mathrm{End}(N)$.

The homomorphism $ψ$ is just the restriction of $φ$ to $A$.

More precisely, $ψ = φ ∘ i$ where $i$ is the canonical homomorphism from $A$ to $S^{-1} A$.

Suppose that $f$ is not only additive, but also $A$-linear.

This means that the image of $ψ$ is contained in $E_f$.

In other words, there exists a homomorphism of rings $ψ'$ from $A$ to $E_f$ with $φ' = j ∘ ψ'$.

For every element $s$ of $S$ the element $ψ'(s)$ of $E_f$ is invertible in $\mathrm{End}(M) × \mathrm{End}(N)$, because $s / 1$ is invertible in $S^{-1} A$ and $ψ'(s) = ψ(s) = φ(s / 1)$.

We have seen that $E_f$ is closed under invertibility, so it follows that $ψ'(s)$ is already invertible in $E_f$.

It now follows from the universal property of the localization $S^{-1} A$ that there exists a unique homomorphism of rings $φ'$ from $S^{-1} A$ to $E_f$ with $φ' ∘ i = ψ'$.

We have $j ∘ φ' ∘ i = j ∘ ψ' = ψ = φ ∘ i$ and therefore $j ∘ φ' = φ$.

In other word, $φ'$ is the restriction of $φ$ to a homomorphism of rings from $S^{-1} A$ to $E_f$.

The existence of this restriction tells us that $f$ is $S^{-1} A$-linear.