The approximation in the question is a particular arrangement of a rational approximation, and other answers have already explained how these can be derived from Padé approximants or with the Remez algorithm for creating minimax approximations. I could not find this particular approximation in a search of relevant literature going back to the 1950s. Searching for the coefficients on the internet, I did however trace it back to a 2011 blog post by Paul Mineiro, and the description there indicates that he derived this approximation himself (see the section "A Fast Approximate Exponential").

In general, a rational approximation $\mathrm{R}_{m,n}(x)=\frac{\mathrm{P}_{m}(x)}{\mathrm{P}_{n}(x)}$, where $\mathrm{P}_{n}$ denotes a polynomial of degree $n$, tends to have an approximation error smaller than a polynomial approximation $\mathrm{P}_{n+m}$. This is one reason rational approximations were very popular in the past, up to about the early 1990s. With processors of the 1950s through the 1980s, floating-point division was often not much slower than floating-point multiplication. For example, on the IBM 7090 a floating-point multiply executed in 16.8 to 40.8 microseconds, while a floating-point divide executed in 43.2 microseconds. On the Intel 8087, a floating-point multiply required 90-145 cycles, while a divide required 193-203 cycles (according to the 1987 Microsoft Macro Assembler 5.0 Reference).

Subsequent work on computer hardware focused on making multiplication very fast, then added the fused multiply-add operation, or FMA, which can execute a multiply and a dependent add in almost the same time as a plain multiply. Speeding up floating-point division is a much harder problem, such that modern processors provide division at a throughput on the order of $\frac{1}{10}$ to $\frac{1}{20}$ of that of multiplication. As a consequence, many modern approximations used for mathematical functions tend to be FMA-accelerated polynomial minimax approximations.

Rational approximations can also present problems when one tries to implement faithfully-rounded implementations of mathematical functions with error of at most 1 ulp, as they accumulate error from two polynomial evaluations plus a division. The accuracy standards for math libraries prior to the 1990s were less strict, often allowing several ulps of error and focusing instead on minimizing the number of numerical constants and the number of operations as both RAM and ROM were very small. Rational approximations could often be rearranged to achieve these objectives.

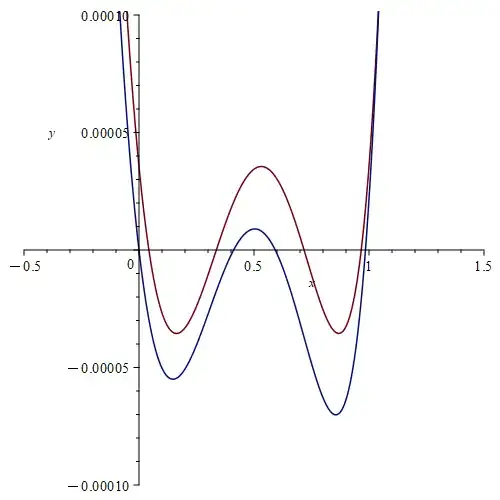

An example is the following approximation (I tweaked the coefficients to get closer to a minimax approximation) to $2^{x}-1$ on $[-1,1]$ crafted by Hirondo Kuki in 1964, using a truncated version of Gauss' continued fraction expansion for $e^{x}$ as a starting point (H. Kuki, Mathematical Functions - A Description of the Center's 7094 Fortran II Mathematical Function Library, University of Chicago Computation Center Report, February 1966, p. 54):

$$2^{x}-1 \approx \frac{2x}{c x^{2} - x + d - \frac{b}{x^{2}+a}}\ \ ,$$

where the values of the constants are $a=87.417032155030128$, $b=617.97007676566318$, $c=0.03465679176500755$, and $d=9.954608304921436$. The maximum relative error of this approximation is $\lt 1.7\cdot10^{-10}$. This level of accuracy is achieved with just nine operations (five additions, two multiplications, and two divisions) and four stored floating-point constants.

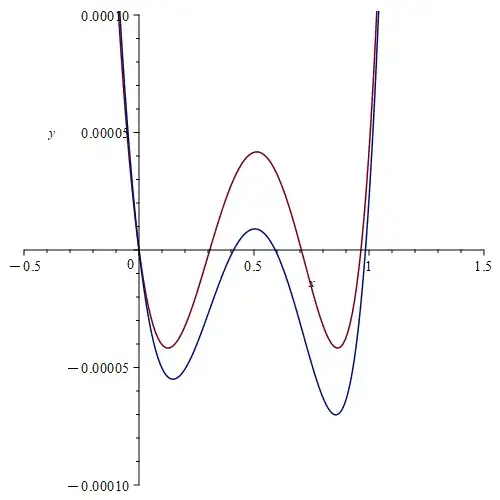

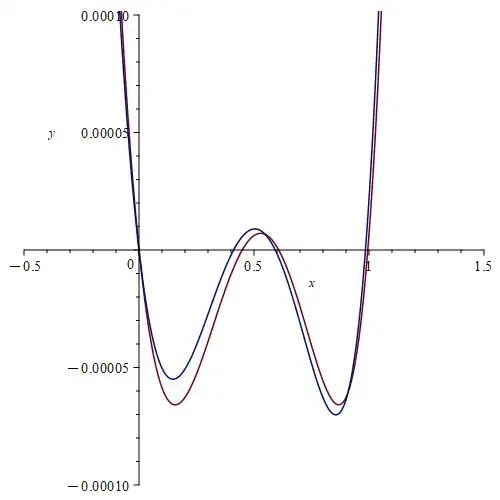

A particularly efficient arrangement for a rational approximation to $2^x-1$ inspired by the Padé approximants for $\exp(x)$ is

$$\mathrm{R}_{m,n}(x) := \frac{2x\mathrm{P}_{m}\left(x^{2}\right)}{\mathrm{Q}_{n}\left(x^{2}\right)-x\mathrm{P}_{m}\left(x^{2}\right)}$$

where $\mathrm{P}_{m}$ is a polynomial of degree $m$ and $\mathrm{Q}_{n}$ is a polynomial of degree $n$. In the 1990s I used an approximation $\mathrm{R}_{3,3}$ of this type to implement the instruction F2XM1 in the AMD Athlon processor. $\mathrm{R}_{1,2}$ for $2^{x}-1$ on $[-1, 1]$ uses $\mathrm{P}_{1}(x^{2}) := 28.937286906710295 x^2 + 2532.7737162012545$ and $\mathrm{Q}_{2}(x^{2}) := \left(x^{2} + 376.0928489774704\right) x^{2} + 7308.0401603051168$ and approximates the target function with a relative error $\lt 2.7\cdot 10^{-11}$ using ten operations.