So while your hands on approach may certainly be pushed to a correct answer I believe a more analytical and abstract approach may help to understand the problem better.

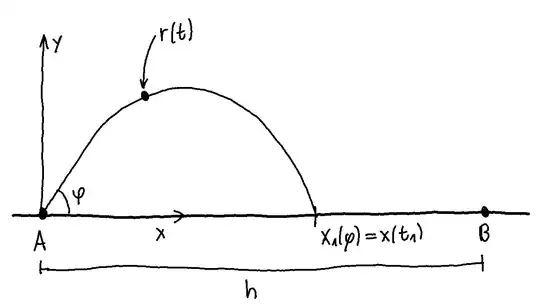

We will disregard air resistance for the sake of simplicity and we also note that we can disregard the length of the field $h$ since we are only interested in shooting into the opponent side of the field. If we shoot in our half of the field it is best to shoot exactly to $h/2$ and one can solve for the angle. Draw a coordinate system as depicted below:

Let $r(t)=(x(t),y(t))$ denote the position of the ball at time $t$ with initial conditions $r(0)=(0,0)$ and $r'(0)=w(\cos(\varphi),\sin(\varphi))$, where $w$ is the speed at which the ball was kicked and $\varphi$ is the angle at which the ball was kicked. Also let $v$ be the speed at which the teams run at each other and let $x_1(\varphi)$ denote the the $x$-coordinate of the ball when it hits the ground at the hitting time $t_1$.

With Newton's laws we can deduce that $r(t)=r'(0)t+\frac{1}{2}(0,-g)t^2$ and hence we get the well known projectile trajectory

$$

x(t)=w \cos(\varphi) t,\text{ }

y(t)=w \sin(\varphi) t - \frac{1}{2}gt^2.

$$

We would like to maximise $x_1(\varphi)$ under the restriction that the ball hits the ground and at the same time we would like to minimise the distance of our team to the ball when it hits the ground as far as I understand.

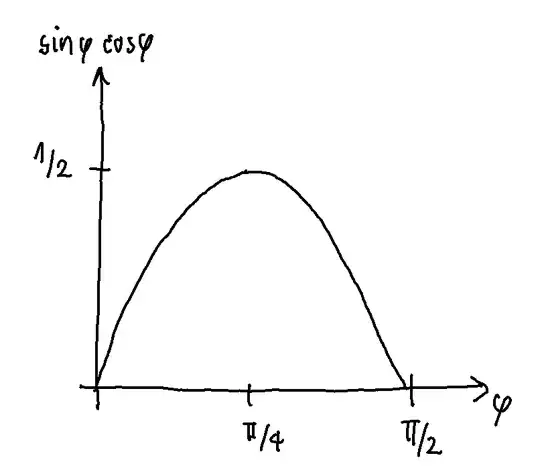

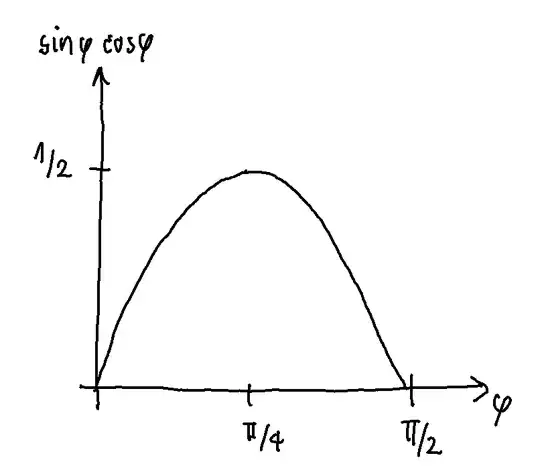

One can easily figure out that $x_1(\varphi)=2\sin(\varphi)\cos(\varphi)\frac{w^2}{g}$ (simply set $y(t)=0$ and plug it into $x(t)$) and hence scales like $x_1(\varphi)\sim \sin(\varphi)\cos(\varphi)$ and this function has one maximum at $\varphi = \frac{\pi}{4}$ which is the optimal angle to shoot the ball as far as possible. Hence we are interested in the interval $\varphi\in I_1=(\frac{\pi}{4}-\varepsilon;\frac{\pi}{4}+\varepsilon)$ for small $\varepsilon>0$.

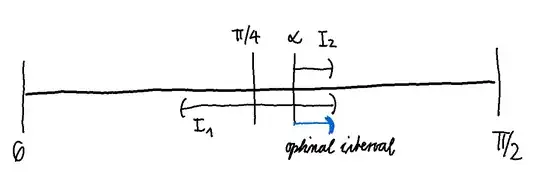

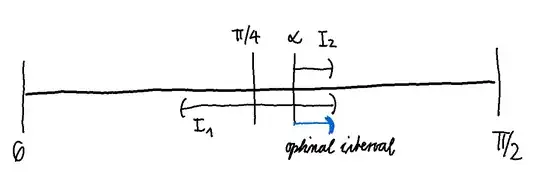

On the other hand we would like be able to receive the ball when it lands, that is the distance between the ball when it landed to our team $d(\varphi)=vt_1-x_1(\varphi)$ should be $\geq 0$. Plugging in the formula above actually reduced the relevant data $\tilde{d}(\varphi)=|v-w\cos(\varphi)|$. This function achieves its minimum at $\varphi=\arccos(\frac{v}{w})$ and including the sign discussion we hence are interested in the interval $\varphi\in I_2=(\alpha;\alpha+\delta)$ for $\delta>0$ small and $\alpha=\arccos(\frac{v}{w})$.

Thus the optimal angles for the rugby ball problem must lie in the intersection of those two intervals $I_1\cap I_2$. Considering that the ball is faster than the players, i.e. $w>v$, we must have $\alpha>\frac{\pi}{4}$. if $\varphi>\alpha$ the team was able to pass the ball already and for $\varphi<\alpha$ the team is still behind the ball.

Conclusion

Plugging in your numbers gives an $\alpha$ which is far too big to actually get a good shot. One would need to run about $\frac{\sqrt 2}{2}$-times slower than shoot (or slightly less) to get a good $\alpha$ close to $\frac{\pi}{4}$. One could also vary the shooting speed $w$ but note that the hitting distance $x_1(\varphi)$ scales quadratically with the shooting speed $w$ and this would be another interesting problem to consider. But under the assumption of fixed shooting speed there is only the possibility to run faster or shoot in your half of the field to go safe. Either way in the realistic dimensions you've given the opponent team will be able to catch the ball first if you try to shoot it as far as possible with respect to shooting angle.