Given a group $G$ with presentation $$G=\langle u,v\mid u^3=v^3=(uv)^3=1\rangle$$ How to prove $G$ is infinite? In general, do we have any systematic methods on finding the order of a group given by presentation?

-

2There is an incompleteness argument that shows the presentation problem is undecidable so there will be no algorithm that will work for all presentations. Problems of this nature are often solved ad hoc with counting arguments using the Sylow theorems or simply by exploring consequences of the presentation. Here you'll want to characterize $u^2, v^2$ and $(uv)^2$ and their inverses to better understand the overall structure of the group. – CyclotomicField Sep 29 '22 at 17:25

-

Please look at the edit to see how to format a presentation properly. – Arturo Magidin Sep 29 '22 at 17:28

-

Your question is phrased as an isolated problem, without any further information or context. This does not match many users' quality standards, so it may attract downvotes, or be closed. To prevent that, please [edit] the question. This will help you recognise and resolve the issues. Concretely: please provide context, and include your work and thoughts on the problem. These changes can help in formulating more appropriate answers. – Shaun Sep 29 '22 at 18:04

2 Answers

It's undecidable from a finite presentation whether a finitely presented group is finite, by the Adyan-Rabin theorem (the trivial group is a positive witness and $\mathbb{Z}$ is a negative witness). In other words, one must use cleverness.

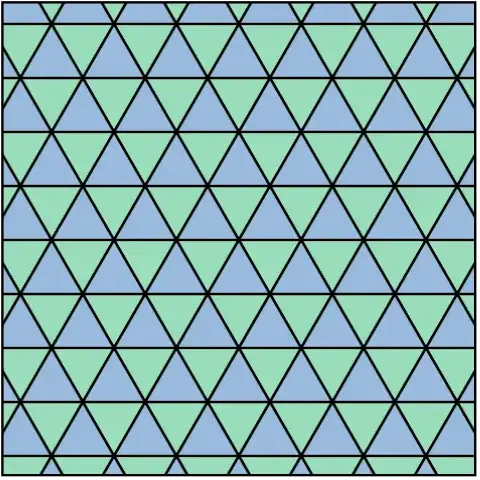

In general, we can try to prove that a group $G$ given by a presentation is infinite by finding a homomorphism into some other group which we know is infinite, and which has infinite image. In this case we are lucky: this group is the von Dyck group $D(3, 3, 3)$, which is known to be the group of orientation-preserving symmetries of the following tesselation of $\mathbb{R}^2$ by triangles:

$u$ and $v$ can be taken to be rotations about two of the vertices of any of the triangles, and $uv$ is a rotation about the third vertex (or so the Wikipedia article claims, but I'm having trouble actually visualizing this...). This gives a homomorphism from $G$ to the oriented Euclidean group $\mathbb{R}^2 \rtimes SO(2)$ (which is even injective but we don't need this) whose image contains translations, and so in particular is infinite.

In general the von Dyck group

$$D(\ell, m, n) = \langle x, y, z \mid x^\ell = y^m = z^n = xyz = 1 \rangle$$

is known to be infinite iff $\frac{1}{\ell} + \frac{1}{m} + \frac{1}{n} \ge 3$; this comes from its interpretation as the group of orientation-preserving symmetries of a tiling of either the sphere, the Euclidean plane, or the hyperbolic plane by triangles, depending on the value of this sum.

- 468,795

Let $\omega=\frac{-1+i\sqrt3}2$ be a third root of unity and consider the bijective maps $U,V\colon \Bbb C\to \Bbb C$ given by $U(z)=\omega z$ and $V(z)=\omega (z-1)+1$ — in other words rotation by 120 degrees around $0$ and $1$, respectively. Show that $U\circ V$ is a rotation by 240 degrees around some point. Conclude that there is a homomorphism $\phi$ from $G$ to the group of permutations of $\Bbb C$ with $\phi(u)=U$ and $\phi(v)=V$. Show that $V\circ U$ is a translation. Conclude.

A possible general strategy is to find a homomorphism to a concretely group. But beware: We did not show that $\phi$ is injective, but that was good enough for showing infinite order.

- 382,479

-

1$U \circ V$ and $V \circ U$ have to be conjugate, don't they? Do you mean $V^{-1} \circ U$? – Qiaochu Yuan Sep 29 '22 at 17:50