I have just finished reading and working through the exercises in the first three chapters of A Concise Introduction to Mathematical Logic by Wolfgang Rautenberg. This material was at the right level for me. It had the kind of thoroughness and rigor that I was looking for, yet was manageable to me as a non-expert.

From here I would like to learn about the infinitary language, $L_{\omega_1, \omega}$, and then learn more about the Lindenbaum-Tarski algebra (which I assume is a $\sigma$-algebra in $L_{\omega_1, \omega}$). I am presently trying to find a good source to work through next.

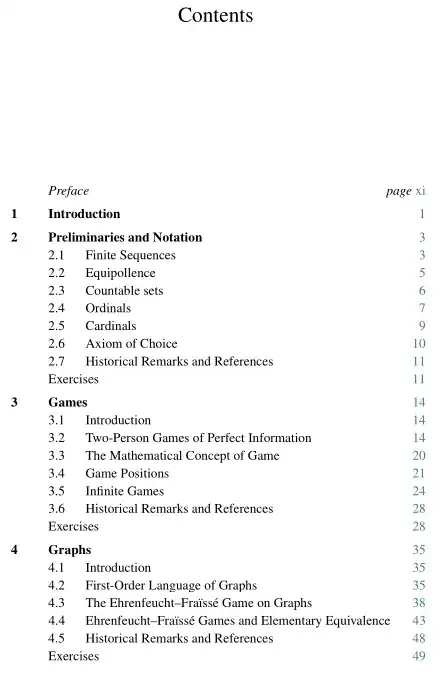

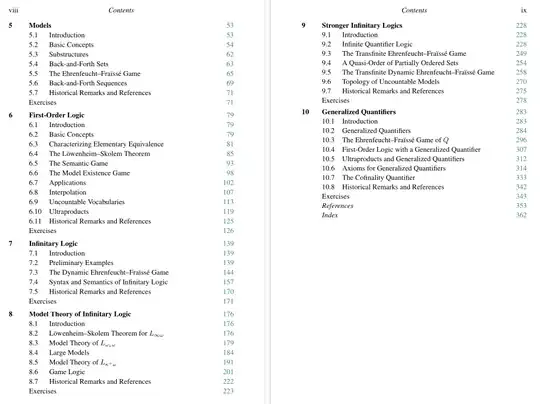

From this answer, I learned about Lectures on Infinitary Model Theory by Dave Marker, and have skimmed through that a bit. I have also skimmed through Model Theory for Infinitary Logic by H. Jerome Keisler. Ideally, I would like to see a thorough treatment of $L_{\omega_1, \omega}$ that roughly parallels what I just read in Rautenberg for $L_{\omega, \omega}$. In particular, some questions that come to my mind are the following.

Are notions like theory, axiom system, consistent, refutable, and definitorial extension defined in the same way and work the same way in $L_{\omega_1, \omega}$? If so, what happens when I take a theory $T$ in first-order logic and consider the theory $T'$ in $L_{\omega_1, \omega}$ determined by $T$? How does it differ? Is there a sense in which it is the "same", according to some definition of sameness? I am particularly curious about the case where $T$ is the theory determined by the ZFC axiom system.

I understand that $L_{\omega_1, \omega}$ is complete. How exactly is the deducibility relation defined? Such a relation is mentioned in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry. The relation there is what I expect from my Rautenberg reading: a relation from a set of sentences $X$ to a sentence $\alpha$, where $X\vdash\alpha$ means that there is a proof of $\alpha$ using sentences in $X$. I can guess at the details of this deducibility relation from the Stanford article, but I would prefer to read a rigorous and properly citable treatment. Both Marker and Keisler seem to only define a unary relation, $\vdash\alpha$, characterizing tautologies. They also don't spend a lot of time on this relation, with Marker including it only in an appendix.

Rautenberg uses $\mathtt{C}^-$ to refer to the property $$ X \cup \{\alpha\} \text{ is inconsistent} \iff X, \alpha \vDash \bot \iff X \vDash \neg\alpha, $$ and $\mathtt{C}^+$ for the analogous property with $\alpha$ and $\neg\alpha$ interchanged. Do these properties still hold in $L_{\omega_1,\omega}$?

Neither Marker nor Keisler seem to spend much time, if any, on the Lindenbaum-Tarski algebra. Is there just not much to say about it in $L_{\omega_1,\omega}$, and I should just work out whatever details I'm interested in on my own? Or is it just that the topic happens to be too far removed from Marker's and Keisler's main focus?

To be clear, I'm not hoping to have these questions answered here. I include them only to give a better idea of what I'm looking for in a reference. My only hope is that someone here can help me decide what book (or books) I should work through next.