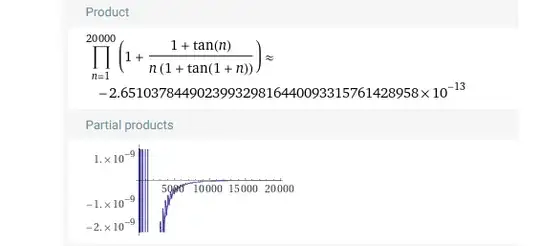

This answer is still partial as contains a mistake (see the edit below) but it may help the thinking process. It also points out some problems of a different answer.

I will build upon the first answer, which shows good intuition but fails to prove that the limit is zero. This will be a heuristic discussion, which I think could be made rigorous by means of theorems like the mean value theorem about the quasi-periodic motion.

I will call the following function

$$ f(x):= 1+\frac{\tan(x)+1}{x(\tan(x+1)+1)} $$

whenever it is defined. It’s just the function that appears in your infinite product evaluated at $n$.

My claim is the following. I claim that the above product converges to zero if the following condition holds:

$$ \int_0^\pi x\ln(f(x))dx <0 $$,

while it diverges if the above integral is strictly positive. You can thus prove directly that this integral is negative to prove your claim, or compute it numerically (or compute it exactly if you manage).

A small remark before “proving” it. Although the function $f$ is unbounded at some values of $x$, the logarithm makes the singularities narrower so that the integral is well defined and finite.

Let’s start from the heuristics of the first answer: what I am going to use is the fact that for integer $n$, we can write $n=\theta+k\pi$ in a unique way with $k$ an integer and $\theta\in[0,\pi)$, and considering all the natural integers, the sequence $\theta(n)$ will lie uniformly on the interval $[0,\pi]$ (whatever that means rigorously). I will then take $\Theta$ to be a random variable with uniform distribution over the interval $[0,\pi)$ and think of the sequence $\theta(n)$ as a sequence of infinite realizations of this random variable.

Consider now our problem. Taking the natural logarithm of (the absolute value of) the above expression and using the properties of the logarithm, we equivalently ask whether

$$ \lim_{N\to +\infty} \sum_{n=1}^N\ln |f(n)|=-\infty. $$

Of course, we are using the fact that $f(n)$ is never zero or infinite for integer $n$.

Since $f$ is periodic of period $\pi$, the above condition rewrites as

$$ \lim_{N\to +\infty} \sum_{n=1}^N\ln |f(\theta(n))|=-\infty. $$

If we then treat $\theta$ as a random variable, we can compute the expected value

$$ \mathbb E(\ln(f(\Theta)))=: E. $$

This quantity is something very concrete, and it turns out that $E$ is exactly the integral that I wrote above.

If $E$ is less than zero, looking at $\theta(n)$ as independent realizations of the variable $\Theta$ then we expect, as a consequence of the law of large numbers,

$$ \lim_{N\to +\infty} \frac{1}{N}\sum_{n=1}^N\ln |f(\theta(n))|=E. $$

and my claim follows. Analogously we can treat the case $E>0$.

If I am not mistaken, this actually tells us that we expect to have a convergence rate to zero of the order $e^{NE}$.

I am sure I have done some mistakes. My point is that we shouldn’t just look at the number of occurrences of terms less than one with respect to all the occurrences, but rather look at what is the average contribution of these occurrences.

Edit. I have just realized that $f$ is actually not periodic because of that $n$, so this argument does not work and has to be substantially modified. Nevertheless, I hope I have showed that one needs better tools to study the problem.