I am reading a book on cryptographic programming and I found an example without proof.

How to prove that $f(x)=x^3 \pmod{pq}$ is bijective for any non negative integer $x<pq$ where 3 is not a factor of $p-1$ and $q-1$?

I did some experiments with Mathematica and I noticed the claim is true.

p = 11;

q = 17;

A = Range[0, p q - 1];

B = A^3 // Mod[#, p q] & // Sort;

A == B

I have no idea how to start proving this.

Note: $p$ and $q$ are two distinct large prime numbers.

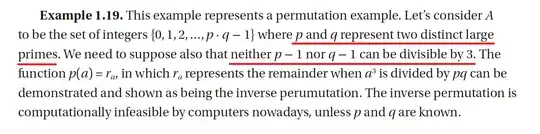

The screenshot of the example: