I think I have a counterexample.

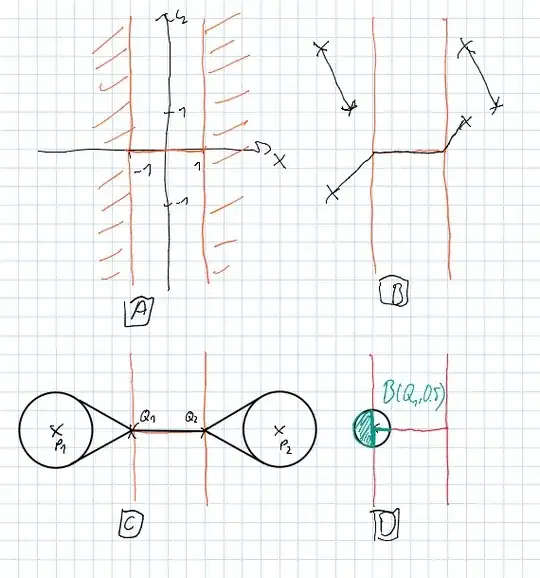

Look at $X=\mathbb{R}^2\setminus\{(x,y)\in\mathbb{R}^2:|x|<1,y\neq 0\}$. Below is a picture of $X$ in red as a subset of $\mathbb{R}^2$ in A.

The metric on $X$ comes from the Euclidean metric. $X$ consists of three parts: "the left part", "the right part" and "the middle part". In each part separately, distances and metric segments are defined as induced by the intrinsic metric from $\mathbb{R}$ - see B for some examples. For two points that lie in different parts, one has to pass through one (or two) "choke points" at $Q_1, Q_2$, but except for that the metric segments consists of two or three usual Euclidean segments.

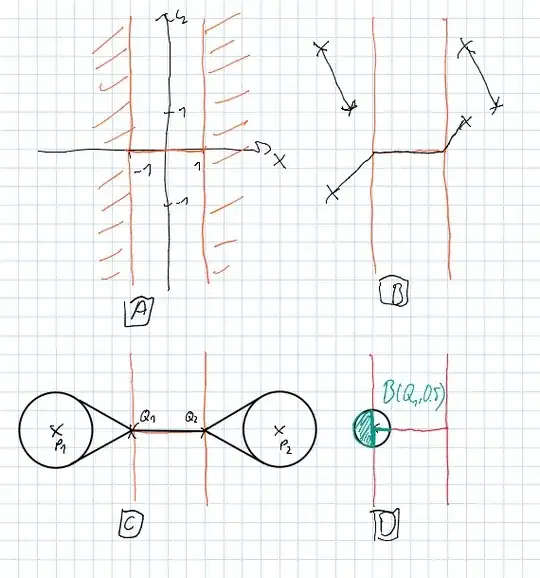

Now take as open set $S$ the union of two open balls: $S=B((-3,0);1)\cup B((3,0);1)$ for $P_1=(-3,0),P_2=(3,0)$. The convex hull $C=\text{conv}(S)$ should be $S$ together with two "open sectorlike shapes" and the "middle part" as depicted in C. If we look at the two "choke points" $Q_1, Q_2$ we see $Q_1,Q_2\in C$, however no open subset containing any of the two choke points is contained in $C$. An open ball around $Q_1$ is depicted in green in D - note that only the green part of the black disc is part of the ball.

Now this is not a formal proof, but I hope it fits. If my intuition derailed me somewhere, please object and let me know.

Remark: In this metric on $X$ all open balls should be identical to their convex hull. If we take the metric induced by the $1$-norm we get open balls that are squares oriented as "diamonds", while their convex hull should be squares oriented as "boxes". If we replace the Euclidean metric by the $1$-metric in the construction with $X$, I think that we do not get a counterexample. If the opening angle at choke points would not be $180^{\circ}$ but larger (suitably adjusting $X$), I guess one would also get a counterexample coming from the $1$-metric. By "$180^{\circ}$" I mean the usual Euclidean angles on $\mathbb{R}^2$ - nothing which has to do with the counterexample metrics.