I was reading this question (Inverse Laplace Transform of $1/(s+1)$ without table) and read the following:

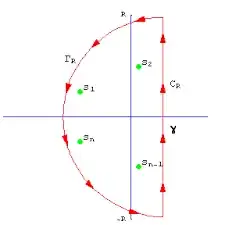

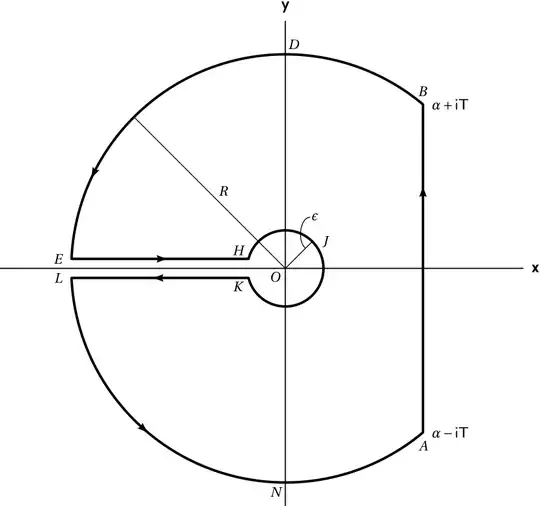

The pole is on the left half plane, so: $$\gamma(t)=\frac{1}{2i\pi}\int ^{i\infty}_{-i\infty}\frac {e^{st}}{s+1}\,\mathrm{d}s$$

What exactly is a "pole" of a function? Based on this other question I was reading (Finding poles, indicating their order and then computing their residues), it seems that the "pole" of a function is at all points where you are forced to divide by 0. Is this correct?

Once you have determined the "pole" of a function - how do you determine that the "pole" of the function 1/(s+1) is on the left half of the plane? Is this done by determining if the "pole" of this function has a "complex part"? (e.g. a + ib)

Thank you!

Note: I am asking this question with regards to calculating Inverse Laplace Transforms. For many common mathematical functions, I am guessing that the "poles" of these functions will be in the "left plane" - and thus, the "Gamma" term in the Inverse Laplace Transform will end up being 0 and thus facilitate the computation of the integral required in the Inverse Laplace Transform. Is this correct?